BEMERKUNGEN ZU PAPYRI XXIX

<Korr. Tyche>

820.–821. Thomas BACKHUYS

Anmerkungen zu BASP 52 (2015) 15–26

820. Nr. 1 („Letter about pentarouroi machimoi“)

Es handelt sich bei dem erstedierten Text um einen aus zwei Fragmenten zusammengesetzten Brief an einen Beamten namens Ἀσκληπιάδης. Der Herausgeber fasst den Inhalt dergestalt zusammen, dass das Anliegen die Steuererhebung durch τελῶναι ist, „who are to be arraigned before the court“ (S. 18). Μάχιμοι haben sich über das Handeln von τελῶναι beschwert, was in Zusammenhang mit ihrem zeitweiligen Umzug vom Memphites, wo ihre Kleroi liegen, in den Arsinoites zu setzen ist. Allerdings sollten die Steuerpächter wohl nicht vor Gericht geladen werden, wie vom Hg. angenommen, sondern im Vorfeld Stellung zu dem Vorwurf beziehen (δικαιολογεῖσθαι, s. unten zu Z. 4), nachdem ein Briefwechsel zwischen Asklepiades und dem Verfasser dieses Schreibens stattgefunden hatte (s. unten zu Z. 2). Die Forderung des Absenders läuft am Schluss darauf hinaus, dass den τελῶναι durch den Adressaten Asklepiades das vermutlich mehrfache Eintreiben von Geldern (πράσσειν) untersagt werden solle.

Hinsichtlich der Datierung des Papyrus tendiert der Hg. aufgrund der möglichen Identifizierung des Adressaten Asklepiades mit dem aus anderen Texten bekannten οἰκονόμος (Pros.Ptol. I 1027 + VIII 1027a) dazu, den Text in die Zeit des dritten Ptolemäers, Euergetes’ I., zu setzen. Diese wäre aufgrund der prosopographischen Informationen reizvoll, wobei jedoch kein Grund — auch nicht die Paläographie — der Datierung unter Philopator zuwiderliefe. Bereits Grenfell und Hunt haben im S. 16 Anm. 4 zitierten Komm. zu P.Tebt. I 5, 44 auf diese Alternative aufmerksam gemacht. Daher sollten für das 14. Jahr, auf das der Papyrus datiert, die Äquivalente 233 oder 208 v. Chr. angegeben werden. Die Monatsangaben auf S. 15 der Ed. müssen korrigiert werden, da sie dort fälschlich an der augusteischen Fixierungen orientiert sind, also: 15. Sept.–14. Okt. 233 oder 9. Sept.–8. Okt. 208 v. Chr.

fr. a 2 ] ̣νοτι: Eventuell γεγράφαμ]ε̣ν, ὅτι - - -, in der vierten Zeile möglicherweise aufgenommen durch etwas wie ἀντέγρα]ψας [1].

3 Dass am Ende der Zeile, wie auf S. 20 vorgeschlagen, zu τῶ[ν τελωνῶν zu ergänzen ist, ist recht wahrscheinlich.

4 Für δικαιολογεῖσθαι scheint nicht, wie im Komm. auf S. 20 vertreten, ein „technical use“ mit der Bedeutung „to plead one’s cause before the judge“ nachweisbar zu sein. Wenngleich das Verb in ptolemäischer Zeit im Zusammenhang mit Organen des Justizwesens wie den Chrematisten (P.Mert. II 59, 9) oder Beamten (P.Enteux. 69, 7; P.Tor.Choach. 12 Kol. III 18 = UPZ II 162; SB I 4512 B 61; VI 8964, 4) ebenso wie das Substantiv δικαιολογία (PSI XV 1515, 3; P.Tebt. III.1, 796, 18; SB XXII 15123, 22) begegnet, bleibt seine Grundbedeutung „sich rechtfertigen“ ohne die Implikation eines speziell juristischen Gebrauchs. Vgl. zur untechnischen Bedeutung v.a. des Verbums das Polybios-Lexikon, Band I, Lieferung 2, bearb. v. A. Mauersberger, 2., verb. Aufl., Berlin 2003, Sp. 533 s.v. δικαιολογέομαι und Sp. 533–534 s.v. δικαιολογία. δικαιολογέομαι bedeutet zunächst „sich rechtfertigen“, und dies kann eben vor Richtern wie den Chrematisten, aber auch vor einem Beamten geschehen. Ein Gerichtsverfahren aber scheint der Verfasser dieses Schreibens gar nicht im Sinn zu haben. Vielmehr wird zu Beginn des Schreibens das bisherige Geschehen referiert: Beschwerde an Asklepiades (γεγράφαμ]ε̣ν [?], Z. 2) – Antwort des Asklepiades (ἀντέγρα]ψας [?], Z. 4): die τελῶναι rechtfertigen sich vor ihm (sc. mit den Vorwürfen konfrontiert), indem sie gewisse Argumente vorbringen (- - - παρεπιδημεῖν, Z. 5). Das Partizip φάσκοντας kann als modale Ergänzung zum AcI δικαιολογεῖσθαι τοὺς τελώνας verstanden werden und würde das δικαιολογεῖσθαι erörtern. Dies wäre dem verbreiteten Gebrauch der Participia coniuncta gemäß[2] , wohingegen der konzessive Gebrauch in diesem Text bei unserer Interpretation von δικαιολογεῖσθαι nicht nahegelegt wird und im Übrigen zu den selteneren Fällen im ptolemäischen Griechisch zählt [3]. Der Hg. versteht den Passus als „… you wrote (?) to us that the telonai should be arraigned before the court, even if they affirm …“ (S. 19); der neuen Interpretation nach bedeutet er dagegen „du hast uns zurückgeschrieben, dass die Steuerpächter sich rechtfertigen, indem sie sagen, …“.

7 ]μ̣β ̣χ̣ ̣η̣ καταβολῇ̣ ἐπιδει̣κνύοντας εισο̣υσα̣ν ο̣[ → ]μ̣β ̣ ̣ τ̣ῆς καταβολῆς ἐπιδεικνύοντας εἰς οὓς ἂν ̣ [. Der Genetiv καταβολῆς anstelle des im Editionstext abgedruckten Dativs καταβολῇ wird im Komm., S. 22 erwähnt. εἰς οὓς ἄν wurde bereits vom Hg. ebd. vorgeschlagen.

fr. b 2 - - - καλ̣ῶ̣ς̣ οὖν ποιήσι̣ς̣ σ̣υ̣ντ̣ά̣ξα̣ς̣ αὐ̣τοῖς μ̣ὴ ο̣ὐκ . ( sic) → (Satzende) καλῶς οὖν ποιήσε̣ι̣ς συντάξας αὐτοῖς μὴ σ̣υκο̣|[φαντεῖν ἡμᾶς: Zu ποιήσι̣ς̣ findet sich im Apparat die Angabe „ l. ποιήσ⟨ε⟩ι̣ς̣“. Epsilon ist undeutlich zu erkennen, für Iota allein ist zu viel Platz. Der Punkt am Ende des wiedergegebenen Passus der Ed. ist verwirrend. Er ist offenbar nicht als Satzzeichen, sondern als Unterpunkt zu verstehen. In der Ed. werden durchweg unsicher gelesene Buchstaben mit dem Satzzeichen anstelle des Unterpunktes gekennzeichnet. (Vermeintlicher) Betrug (συκοφαντεῖν), ausgehend von den Steuerpächtern (τελῶναι), ist urkundlich gut bezeugt; in ptolemäischer Zeit: CPR XXVIII 11; P.Gen. III 126; P.Hels. I 12; P.Mich. XVIII 774; SB XIV 11893; UPZ I 113. Bei dem letztgenannten Text UPZ I 113 handelt es sich gar um einen Erlass aus dem Büro des Dioiketes Dioskurides an Dorion, in dem es heißt (Z. 14–17): ὅπως μηθὲν ἔτι τοιοῦτο γίνηται | μή τε ἀδικῆται μηθεὶς ὑπὸ μηδενός, μάλιστα δὲ (?) τῶν | συκοφαντεῖν ἐπιχειρούντων τελωνῶν, αὐτοί τε παρα|φυλάξασθε - - -.

3 Die Lesungen in dieser Zeile lassen sich anhand der Abbildung auf S. 21 nicht mit absoluter Sicherheit überprüfen. Bleibt man aber bei den vorbehaltlichen Lesungen τ̣α̣ α̣υ̣τ̣α̣ πράσσο̣ν̣τ̣α̣ς̣, könnte man dies als τὰ αὐτὰ πράσσοντας „dasselbe (sc. an Steuern) eintreibend“ verstehen. Die Buchstaben unmittelbar davor ließen sich vielleicht als δί̣ς̣ lesen, mit einem immerhin erkennbaren Delta und zwei unsicheren Buchstaben. Dies würde das Anliegen des Absenders insofern erklären, als dass er fordert, dass die τελῶναι von ihnen nicht „zweimal dasselbe einfordern“, nämlich das eine Mal im Memphites, in dem die Kleroi liegen, und das andere Mal im Arsinoites, wohin die πεντάρουροι μάχιμοι sich zeitweise begeben haben. In einem anderen Zusammenhang, einem privaten Darlehensvertrag, ist die zweifache Inanspruchnahme (πρᾶξις) durch den Gläubiger ausgedrückt durch die Worte δὶς {τὰ} ταὐτὰ π̣[ρά]ξειν με (P.Dion. 9, 24; ca. 139 v. Chr.). Vor δί̣ς̣ ist in dem Kairenser Schreiben noch - - - ων zu lesen.

Es handelt sich bei dem Dokument nicht um ein σύμβολον. Der Imperativ der 2. Person Singular μὴ ὄκνει (Z. 7) spricht eindeutig für einen Brief.

2 ]ε̣ μ̣ὴ̣ ἐγ̣λιπ[εῖν → ]ε̣ μὴ ἐγλιπ ̣[: Ebenfalls möglich ist eine partizipiale Form, zumal nach π Reste eines kleinen Buchstabens zu sehen sind, für den ε unwahrscheinlich ist, also e.g. ἐγλιπό̣[ντα.

4a ]δουναι ἔδ̣οξ’ ἑκασ̣τ̣[ → ] ̣ δοῦναι ἔδοξε καὶ τ ̣[: τ ̣[ ist Artikel und wohl Teil des Dativobjekts zu ἔδοξε.

6 ε̣ις ohne Diacritica, da z.B. auch die Partizipialendung -εις möglich ist.

7 μ]ὴ̣ ὄκνει γράφειν ὀφει̣[λ- → - - -, μ]ὴ ὄκνει γράφειν. ὀφει̣[λ-: Zum Satzende nach γράφειν („zögere nicht, zu schreiben“) s. bereits Komm., S. 24. ὀφείλω ist finites Verb des neuen Satzes. Zur Konstruktion χάριν ὀφείλειν siehe P.Cair.Zen. I 59057, 4: τούτου δὲ γενομένου ἐπ̣ί̣[στ]α̣σο, ὅτι ὀφειλήσω σοι χάριν ἱκανήν. Der Ausdruck ist auch in der griechischen Literatur geläufig: Thuk. II 40, 4 (βεβαιότερος δὲ ὁ δράσας τὴν χάριν ὥστε ὀφειλομένην δι’ εὐνοίας ᾧ δέδωκε σῴζειν); Theokr. II 130 (νῦν δὲ χάριν μὲν ἔφαν τᾷ Κύπριδι πρᾶτον ὀφείλειν); Plut. Publicola 23, 4 (ἀλλὰ πᾶσαν ὀφείλων χάριν) etc. Möglicherweise bediente sich der Schreiber hier einer Ausdrucksweise wie ὀφειλήσω σοι πᾶσαν χάριν - - - (Z. 7–8). Diese Ergänzung spräche für kurze Zeilen.

8 οὗ ὁ̣ ἐντ̣ο̣[ → οὐθεν ̣ ̣ [. Wie im Komm., S. 24 angemerkt, passt ein ἐντολεύς nicht gut in den Text. Statt des ο ist θ zu lesen, sodass eine Form von οὐθέν/οὐθείς zustande kommt.

Thomas BACKHUYS

In the Roman period weavers are well attested in Philadelpheia. In AD 123 the weavers’ guild pays 484 dr. to the ἐγλήπτορες γερδίων (BGU VII 1591.15). Since the weavers’ tax is normally 38 dr. the guild consisted of 13 members, no doubt household heads. In AD 139 the guild complains that four of its twelve members were on a mission to Alexandria and that the remaining eight were hard pressed to fulfill their obligations to the state (BGU VII 1572). These obligations are specified in BGU VII 1564, where the weavers receive a payment for manufacturing cloths and a blanket for the army. A small archive of receipts for the weavers’ tax for the period AD 123–140 is preserved in P.Phil. 23–30; no doubt BGU VII 1591 was part of the same find[4].

BGU VII 1615 (TM 9520) is a list of ten weavers’ families (γέρδιοι), dated a generation earlier, in AD 84. The text is complete and the editors have noticed that several persons of this list recur in P.Lond. II 257 (pp. 19–28; AD 94). This list deals with several villages; the weavers of Philadelpheia are loosely grouped in ll. 96–105 and 139–176. Finally, more than 30 weavers are listed in the archive of the praktor Nemesion, in the second quarter of the first century AD (P.Princ. I 1–3, 9–13; SB XVI 12737–12739). Here they pay as individuals for the poll tax, not as families for the weavers’ tax. In a few cases a family continuation is not unlikely.

Starting from BGU VII 1615 I have looked for prosopographical and genealogical overlaps in the other texts.

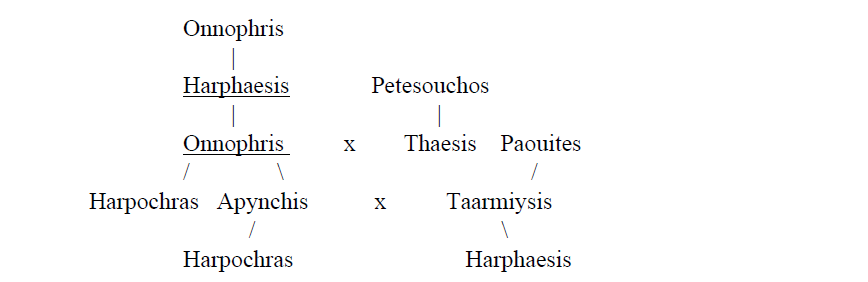

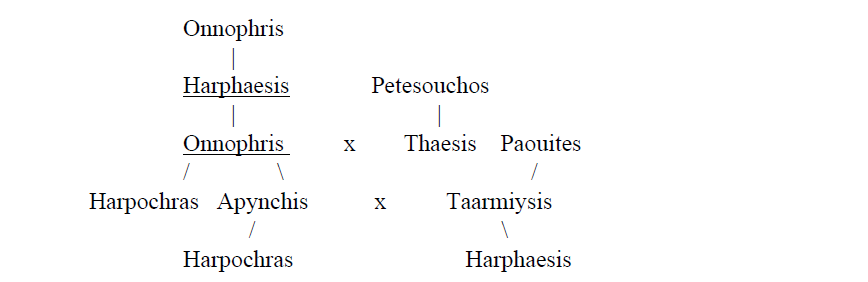

5. Ὀννόφρις Ἁρφαήσιος καὶ Ἁρποχρ[ᾶς] → Ὄννοφρις Ἁρφαήσιος καὶ Ἁρποχρ[ᾶς υἱός]: in P.Lond. II 257.161–162, as was already pointed out in the notes of BGU VII 1615, his son Apynchis, son of Onnophris, grandson of Harphaesis, has taken over the family business. Apynchis’ son Harpoch(ras) is also a γέρδιος. This allows us to reconstruct the following stemma (persons found in both texts are underlined):

The filiation Onnophris son of Harphaesis is found in two lists from the Nemesion archive (P.Princ. I 10 iii.21 [AD 34]; SB XX 14576 xvi.430 [AD 43]), but the names are too common to be certain of a family relationship.

7. Ψάμμις Ἀσκλᾶτος καὶ Ἀσκλᾶς [- - -] → Ψάμμις Ἀσκλᾶτος καὶ Ἀσκλᾶς [υἱός]: as already indicated in the note of BGU VII 1615, the same person is found in P.Lond. II 257.169–170: Psammis, son of Ask[las], grandson of Papontos, weaver, and his son Asklas, also weaver.

8. Ἡρακλῆς Μυσῶτος [- - -] → Ἡρακλῆς Μυσθ̣ᾶ̣τος [- - -]: I have corrected the reading on the basis of the online photograph (Μυσως is a ghostname). In P.Lond. II 257.194 one house belongs to Mysthas, son of Herakles, who is a farmer of public land [δη(μόσιος) γ(εωργός)]. The filiations Mysthas, son of Herakles, and Herakles, son of Mysthas, are found several times, for different persons, in the archive of Nemesion (P.Corn. 21 + P.Princ. I 12 xi.284–285, 305; SB XIV 11481 ii.8; P.Princ. I 14 ii.3; P.Princ. I 1 ii.23; P.Princ. I 8 ix.5; P.Princ. I 9 iii.10, 13; SB XX 14576 vo vii.144; P.Princ. I 2 vi.24).

11. Ἆπις [[Ἁρθ̣ω( )]] καὶ υἱοὶ β [→ Ἆπις (Ἄπιτος) καὶ υἱοὶ β [: the name of the father, first written as Αρεω( ), is corrected and a horizontal line is drawn through the original name. Such a horizontal line indicates that father and son have the same name. Instead of (Ἄπιτος) one could also transcribe (ὁμοίως). The same family is found in P.Lond. II 257.139–142, where Apis, son of Apis, grandson of Apis, γέρδιος, has three sons (Apis, Herakles and Onnophris).

Apis, son of Apis, who pays the weavers’ tax in AD 139 probably belongs to the next generation of the same family (P.Phil. 31.4; BGU VII 1616.4).

12. Διονύσις Νεκφερ(ῶτος): as already seen by the editor, the same man, with the combination of Greek and Demotic names, is found in P.Lond. II 257.105, where he is the grandson of Mysthas and also a weaver.

13. [Π]ε[ε]θ ̣ ̣ Ἁρμούσι[ο]ς → Μ̣υσθᾶ̣ς Ἁρμιύσι[ο]ς: the remaining traces allow the reading Μ̣υσθᾶ̣ς here, a very common name in first century AD Philadelpheia[5]. The iota in the patronymic is small and slightly damaged, but there is no reason to doubt it (nor to read it as omikron). Harmiysis, son of Mysthas and Tanekpheros, grandson of Harmiysis, and his brother Mysthas in P.Lond. II 257.100–101, both weavers, are certainly members of the same family, and perhaps Mysthas in BGU VII 1615 is the father of the two brothers in P.Lond. II 257. The filiation Harmiysis, son of Mysthas (without occupation), is found in two texts from the Nemesion archive, two generations earlier (SB XVI 12738 iii.12 [AD 35]; SB XX 14576.384 [after AD 46/47]).

16. Κεφάλων Πε̣τ̣ε̣σούχ(ου) [: the dotted letters were put in square brackets by the editor.

] καὶ Πετεσοῦχ(ος) ̣[: no doubt the same man as in P.Lond. II 257.96, where he is also followed by his son Petesouchos like here. The small trace just before the lacuna does not fit for υ̣[ἱός], but it could be the beginning of the horizontal line indicating homonymy between father and son: Πετέσουχ(ος) (Πετεσούχου). Because the London text does not give an occupation the identification cannot be proved.

17. καὶ Ἀσκλᾶς [- - -] → καὶ Ἀσκλᾶς (Ἀσκλᾶτος): the long horizontal stroke after the name clearly indicates homonymy of father and son. He is no doubt identical with one of the two homonyms in P.Lond. II 257.41 and 43 (where the occupational titles are lost).

18. Ὄννοφρις Πανεσνέος is identical with the homonymous person in P.Lond. II 257.164, who has two sons, Σανσν[εύς] (rather than the editor’s Σανσν[ως]) and Heras. Since the latter is called γέρδιος (l. 166), this is a weavers’ family again.

20. Ἀρχωνᾶς Πανεγβη(οῦτος) → Ἀρχωνᾶς Πανετβη(οῦτος): this is the same person as the weaver Archonides, son of Panetbeus, in P.Lond. II 257.175. In both cases the patronymic has to be corrected, as shown by J. Quaegebeur, Enchoria 4 (1974) 24 n. 25. In the London papyrus the next house is that of Phasis son of Psamis (Φάσις Ψάμιδο(ς) γέρδιος). This is no doubt the colleague mentioned at the end of the same line in the BGU text, where I propose Φάσ[ι]ς Ψά[μιδος] instead of Φᾶσ[ι]ς Φά[σιος(?)].

22–23. Πέτεσις καὶ Π[έ]τ[ε]σις υ[ἱὸ]ς [- - -] καὶ Πετεσῖς [- - -] → Πέτεσις (Πετέσιτος) καὶ Π[έ]τ[ε]σις υ[ἱὸ]ς: the horizontal stroke indicating homonymy of father and son has been omitted by the editors. We have here at least three generations with the same rare name Petesis (with epsilon, and clearly different from Πέτησις). The same family is mentioned in SB XVI 12739.25–27 (AD 35/36), where Petesis (a grandfather?) has three homonymous sons called Petesis (note also the genitive Πετέσιτος, which shows this is not an Isis name).

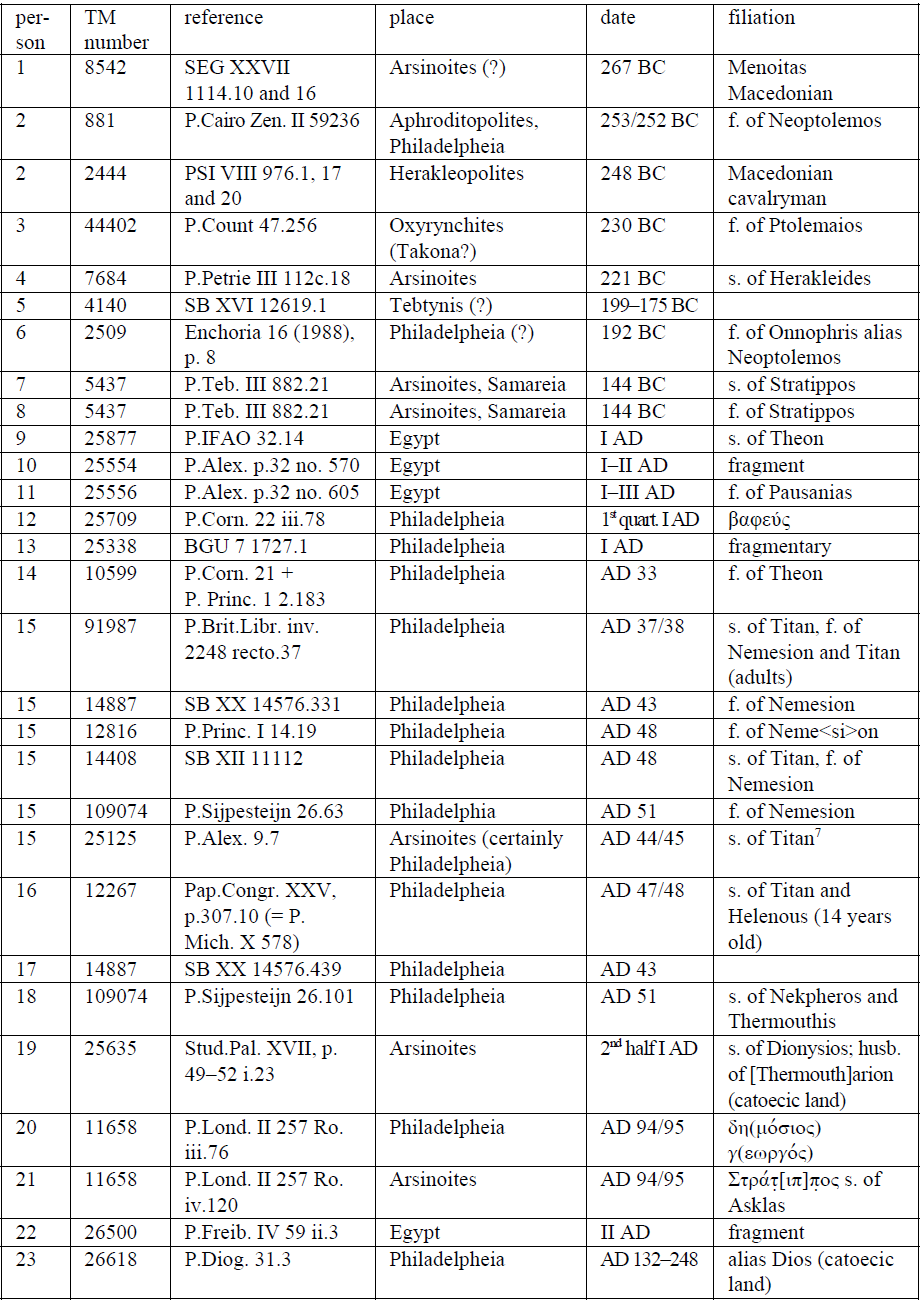

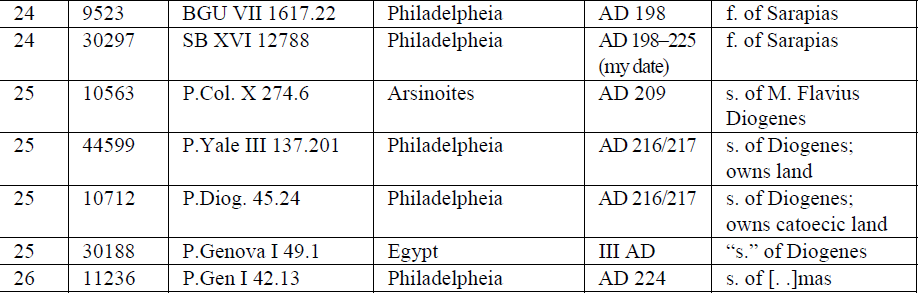

Stratippos is not a common name. It is found 36 times in the papyri for at most 26 different persons, as can be seen in the following list [6].

In the Ptolemaic period the name Stratippos, “army-horse”, is mainly found in military surroundings: Stratippos (no. 2) and his son Neoptolemos are both cavalry soldiers and cleruchs; Ptolemaios, son of Stratippos (no. 3), is an ἐπίγονος, a military settler; Stratippos (no. 4), son of Herakleides, is a Syracusan hundred-arourae cavalryman; Stratippos, son of Stratippos, in nos. 7–8 belongs to a company of Jewish soldiers in the village of Samareia. I have argued elsewhere that Stratippos (no. 6), the father of Onnophris alias Neoptolemos, is a grandson of Stratippos (no. 2) [8].

All Roman examples of the name come from the Fayum, and where a more precise provenance is available it is the village of Philadelpheia [9]. One family is particularly well attested in the early Roman period: Stratippos (no. 15), son of Titan, was the father of Titan and Nemesion (SB XII 11112 and P.Lond. inv. 2248 [ined.], where the three generations are mentioned side by side). Thanks to the unpublished verso of Claudius’ famous letter to the Alexandrians we know that Stratippos and his sons Nemesion and Titan were “privileged farmers involved with the imperial estate of Gaius and Gemellus”[10]. The other six persons with that name in the first century AD are less clear: no. 16–18 and 20 are again from Philadelpheia, and this may also well be the case for no. 19 and 21.

At the very end of the second century AD Stratippos alias Dios (no. 23; his patronymic is lost) buys through a parachoresis a plot of catoecic land from M. Tullius Apollonios; both parties are inhabitants of Philadelpheia. Sarapias, daughter of Stratippos (no. 24), makes a payment in a list of well-to-do persons including a gymnasiarch, an achiereus, a strategos and a hypomnematographos. The other text where she appears, SB XVI 12788, is a receipt for grain transport by the sitologoi of Philadelpheia. There is no doubt that this is the same person and that the text may be dated to the early third century AD. As to Stratippos (no. 25), son of Diogenes, he owns more than 10 arourae of land (P.Yale III 137.10), which is specified as catoecic in P.Diog. 45.24. I have tentatively identified him above with the author of a letter, starting “Stratippos greets his father Diogenes” and perhaps written from Alexandria (proskynema for Sarapis). It is tempting to identify him also with the minor M. Flavius Stratippos, son of M. Flavius Diogenes, in the contemporary P.Col. X 274, who owns catoecic land in Philadelpheia.

The Greek name Stratippos was originally chosen by Greek or Macedonian soldiers as a token of their career. One family of cavalrymen (it is not by accident that Stratippos [no. 2] calls his son Neoptolemos) settled in the later third century BC in Philadelpheia. Whereas the name disappears from the record in Roman Egypt, it is used by one or more well-to-do families in Philadelpheia. The catoecic land they own in the first and second centuries AD may ultimately derive from the grant to Stratippos and Neoptolemos in the time of Zenon. In any case the survival of a personal name over five centuries illustrates the strength of onomastic family traditions.

L. 81 is much shorter than the other lines introducing a new house with owner. Clearly there is no place here for the genealogy with father, grandfather and mother as in other cases. The name of the owner is read as: [- - -]χου Θεουμ[ by the editor. Names beginning with Θεουμ[ are otherwise unknown. The three inhabitants of the house are Panomgeus, son of Onnophris (49 years old), his half-brother Onnophris, son of Nekpheros (49 years) [11], and Onnophris, son of the latter (34 years). If the ages are exact the two half-brothers were born in the same year and Onnophris sr. was only 15 at the birth of his son Onnophris jr. There seems to be a scribal error here. All three persons are priests (ἱερεύς), an occupation which is not otherwise found in the list. Therefore I suggest that the name of the owner should be read as [Σού]χου θεοῦ μ[εγάλου] and that the house (or immovables) were owned by the god Souchos, not by a private person [12]. No member of the family seems to be known from other texts, though Onnophris son of Nechtpheros in SB XVI 12738 iv.11 (Philadelpheia; AD 34) may be a relative. It is not certain, however, that this house was in Philadelpheia. The London papyrus deals with the meris of Herakleides, including Philadelpheia among other villages (cf. BGU VI 1614 introd.).

SB I 4964 (TM 98540) is a funerary stela, no doubt from Terenouthis, figuring the deceased laying on a couch and holding a cup in his right hand. It was published by Pridick in a Russian journal, and was included by F. Preisigke in the Sammelbuch. The editor reads the text as Ἰνααρωσα Χεμφ̣α̣μίας φιλότεκνος ἐτῶν ξε. Preisigke, who saw the photograph in the editio princeps, expressed some doubts about the reading of the first line: “Das Abbild zeigt vor X noch einen unleserlichen Buchstaben.” The excellent photograph in S. Hodjash, O. Berlev, The Egyptian reliefs and stelae in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow , Leningrad 1982, p. 286 no. 210 now allows to read without doubt (the pi is faint, but recognisable): Ἰναάρως ἀπὸ Χεμφ̣α̣μίας. The feminine noun Ἰνααρωσα disappears herewith from our onomastica (the figure on the stela is clearly a man). The form with double alpha is very rare (a few examples in P. Köln XIII 522.13; 523.14; SB XVI 12606.9; XX 14716), but announces the form Naaraus, which is common in the later period.

Willy CLARYSSE

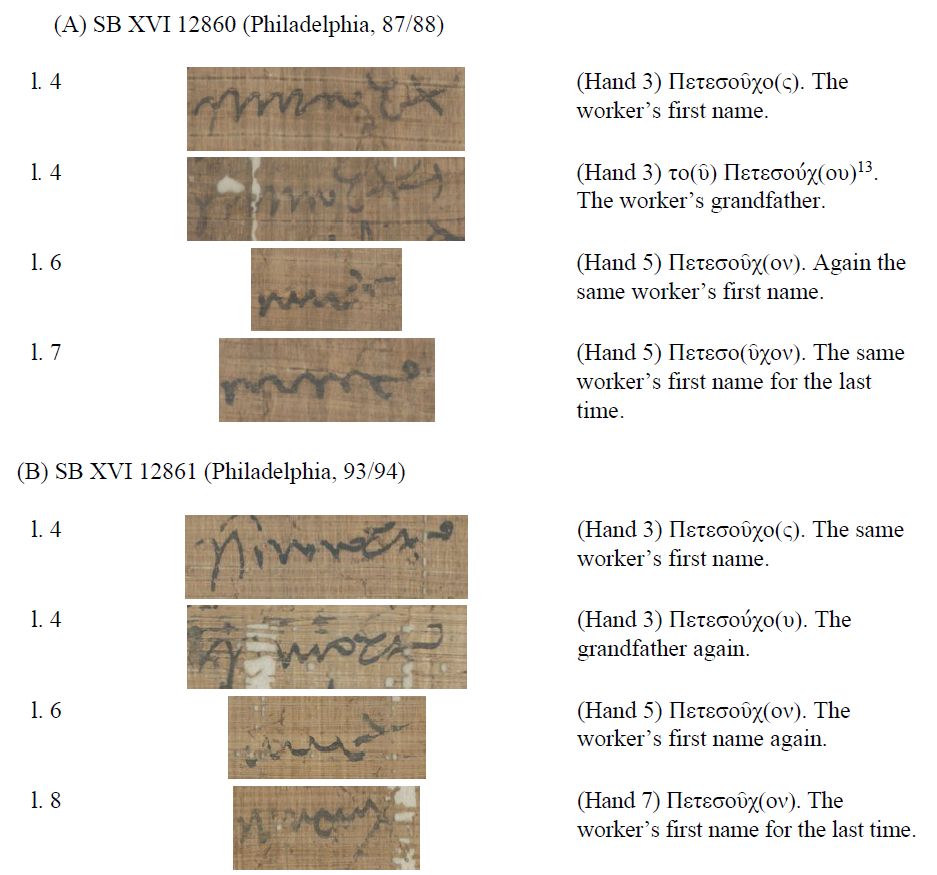

Working on a forthcoming article (BASP 54 [2017]) about unpublished penthemeros certificates from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, I have come across the ways in which the name “Petesouchos” is written, or more precisely abbreviated, in three documents of this type. The fact that P. J. Sijpesteijn has read it properly in two certificates of this kind, SB XVI 12860 (Philadelphia, 87/88) and 12861 (Philadelphia, 93/94), especially l. 6 in both certificates, has led me to check the ways in which this particular name was read in P.Sijp. 42c and 42d. The sections in which Petesouchos’s name appears in SB XVI 12860 as well as 12861 are excerpted and given here side by side with their transcriptions.

The abbreviation of the name in l. 6 of both certificates is striking. One can recognize a pi at the beginning, then a zigzag and finally a raised chi as an indication of abbreviation. The zigzag between the pi and chi should be conceived as the three letters which stand between the pi and chi, i.e. -ετε-. One would then read this abbreviation as Πετεχ( ). This would have left the way open to many possibilities, such as Πετεχ(ῶν), Πετεχ(ῶνσις), etc.[14]. However the fact that this is a repetition of the worker’s first name, i.e. Petesouchos in both receipts, compels us to perceive this abbreviated name as Πετεσουχ( ), even though one cannot see or recognize the three letters, i.e. -σου-.

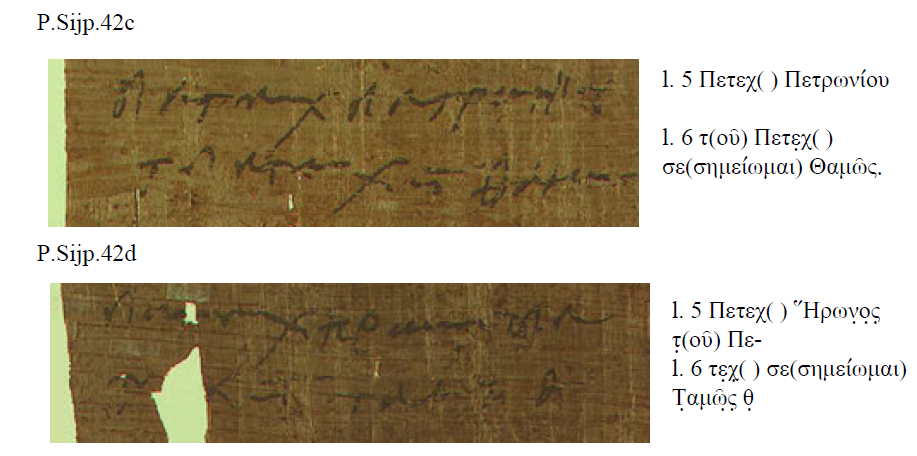

A similar manner of writing the name of Petesouchos is seen in P.Sijp. 42c and 42d, where the editor prints Πετεχ( ) four times. The texts were both written somewhere around and/or in Tebtynis before the 6th–10 th of September 174, the day on which the certificates were handed over to the workers. The name of the worker in the first text is given as Πετεχ( ) Πετρωνίου | τ(οῦ) Πετε̣χ( ), while the second worker is said to be Πετεχ( ) Ἥρων̣ο̣ς̣ τ̣(οῦ) Πε|τε̣χ̣( ). It is true that these two certificates are about eighty years later than the above-considered SB texts; nevertheless, they show graphic similarities.

The editor has perceived that these names are abbreviated, but she was not able to provide the correct solution for them and accordingly was not able to identify them. In her translation she gave the names asPetech(onsis), Sohn des Petronios, Enkel des Petech(onsis) and Petech(onsis), Sohn des Heron, Enkel des Petech(onsis). Commenting on this she states: “Für die Auflösung des in beiden Quittungen abgekürzten Namens Πετεχ( ) gibt es natürlich viele Möglichkeiten, wie ein Blick in die Namenbücher zeigt; ich habe bei der Übersetzung den häufigst bezeugten Namen exempli gratia eingesetzt.” I give below the reading of the editor opposite the photos to further illustrate my point.

It should be kept in mind that these two certificates, written by the same hand, were handed over to two workers who were recruited to work on the same embankment during the same period, i.e. from the 9th to the 13th of Thoth of the 15th regnal year of Marcus Aurelius (174/5 AD), on behalf of the same village, i.e., Tebtynis. This cannot be a mere coincidence, and it will accordingly have had an impact on the identification of these two persons and their family connections.

Based on the examples of SB XVI 12860 and 12861 given above, I have no doubt that the correct reading in the first instance is not Πετεχ( ) Πετρωνίου | τ(οῦ) Πετε̣χ( ), but Πετεσοῦχ(ος) Πετρωνίου | τ(οῦ) Πετε̣σούχ(ου). In the second instance I am sure that the worker’s name is also to be read as Πετεσοῦχ(ος) Ἥρων̣ο̣ς̣ τ̣(οῦ) Πε|τε̣[σού]χ(ου). While the lacuna in P.Sijp.42d.6 prevents us from seeing how the scribe wrote the epsilon before the chi, we can clearly see this in the other three instances; P.Sijp.42d.5, P.Sijp.42c.5 and 6. In l. 5 of both certificates, there is a short wavy stroke between the epsilon and chi. In P.Sijp.42c.6 (and probably also P.Sijp.42d.6), the scribe raised his pen and then put it down to draw the chi. These movements are done intentionally and there must have been a reason for them. I think that these are Verschleifungen for the name Πετεσοῦχος. This may remind us of the manner in which the titles of emperors are recorded in this kind of certificates.

Furthermore, instead of reading σε(σημείωμαι) Θαμῶς at the end of P.Sijp.42c.6, one should read μη(τρὸς) Θαμο̣ύ̣(νιος). Again what is read as σε(σημείωμαι) in P.Sijp.42d.6 is the abbreviation of μη(τρός) and the supposed Τ̣αμῶ̣ς̣ θ̣ should accordingly be the mother’s name. It is not so straightforward what the name is. Both Ταμύσ̣[θ]α̣ς̣ [15] and Ταμο̣ῦθ̣( ) are possible here. The precise identification of one of these Petesouchoi will, however, clear the confusion, see infra.

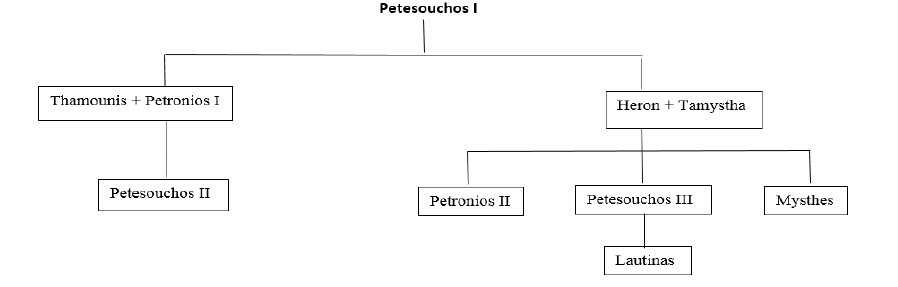

The date and the locality mentioned in the text allow us to identify both of these Petesouchoi. Petesouchos, son of Heron, is no doubt the father of the well-known Lautinas, whom we know from O.Tebt.Pad. 1–59 and after whom the whole archive is named [16]. The archive attests two brothers of Petesouchos, son of Heron; one of them is called Petronios, the other one Mysthes (Μύσθης). Because of the latter, I would prefer to read the hitherto unknown mother’s name of Petesouchos, son of Heron, in P.Sijp.42d as Ταμύσ̣[θ]α̣ς̣ rather than Ταμο̣ῦθ̣( ). Accordingly, the worker’s name in l. 5–6 is Πετεσοῦχ(ος) Ἥρων̣ο̣ς̣ τ̣(οῦ) Πε|τε̣[σού]χ(ου) μη(τρὸς) Ταμύσ̣[θ]α̣ς̣. The other worker’s full name in P.Sijp.42c, as stated above, is Πετεσοῦχ(ος) Πετρωνίου | τ(οῦ) Πετε̣σούχ(ου) μη(τρὸς) Θαμο̣ύ̣(νιος).

Given the fact that these two men performed the five-day corvée for the same village, it is hard to imagine that these two persons, with identical first names and papponymics, are not related. It is rather likely that they had the same grandfather and, thus, that their fathers were brothers which would also explain why Heron, son of Petesouchos, named one of his sons Petronios: he was called after his uncle. Again this would not be a surprise since naming offspring after relatives is a well-known phenomenon throughout the ages. In order to avoid perplexity between these Petesouchoi and Petronioi in the future, from now on every one of them will be given a Latin number; so the grandfather of both Petesouchoi will be Petesouchos I, whereas Petesouchos, son of Petronios, will be Petesouchos II and Petesouchos, son of Heron — the father of the well-known Lautinas, see supra —, will be Petesouchos III. In the same way Petronios, the uncle of Lautinas and the brother of Petesouchos III, will be Petronios II, whereas Petronios, the father of Petesouchos II, will be Petronios I. Thanks to the new readings we now also know that the mother of Petesouchos III is called Tamystha, while the mother of Petesouchos II is called Thamounis. These suggestions extend the family-tree of Lautinas substantially, as we can see from the following figure.

Stemma of Petesouchos’ Family

Usama GAD

Dated to 137, this is one of the very few documents in section XII of CPJ, which collects evidence from the period between the end of the Jewish revolt and the death of Constantine (117–337). The text is a petition to an Arsinoite strategus submitted παρὰ Ἰσακοῦ(τος) τῆς Ἡρακλείδου μετ[ὰ] | κυρίου τοῦ υἱοῦ Τιμοκράτους τοῦ | Ἀπίωνος (ll. 3–5). According to M. Stern, CPJ III 455 introd., the petitioner’s name ‘makes it very probable that Isakous was a Jewess. Though we cannot quote another example of Isakous in the Jewish onomasticon, and such derivatives were hardly common, we may compare Joanna, the feminine form of Joannes … It may be suggested in view of the great popularity enjoyed in the Graeco-Egyptian environment by names like Isarous … that Isakous got her name because it sounded like them.’ The names of the pretitioner’s family members do not indicate a Jewish milieu, but this is not conclusive by itself. It is also remarkable that her name has remained an hapax since the publication of this text in 1927. However, on closer inspection this turns out to be a ghost: as we may see from the on-line images (links at http://papyri.info/ddbdp/psi;8;883, last accessed on 16.11.2016), what was read as kappa is a combination of rho and iota (cf. μερίδω[ν] in l. 2), and the presumed abbreviation stroke is a mere extension of the right branch of upsilon. We should thus read Ἰσαρίου. Ἰσάριον was a common female name, especially in Roman Fayum. PSI 883 does not belong in CPJ.

Nikolaos GONIS

Aufgrund eines freundlicherweise vom Center for the Tebtunis Papyri in Berkeley zur Verfügung gestellten Photos konnte der lückenhafte Text der Zeilen 17–18 dieser Petition eines Inhaftierten vervollständigt werden, in denen ein Teil des Inhalts eines Amnestieerlasses Kleopatras I. und Ptolemaios’ VI. referiert wird (vgl. C.Ord.Ptol. All. 372). In der Edition ist der Passus folgendermaßen wiedergegeben:

![]()

In Z. 17 ist vor ευθη kein γ, sondern — erkennbar an einer Unterlänge und den Resten eines Bauches — ein ρ zu lesen (vgl. die Abbildung in P.Coll. Youtie I, pl. V). Am Beginn der folgenden Zeile steht an dritter Stelle statt eines α ein ε, wobei der untere Bogen größtenteils den Abschabungen der oberen Papyrusschicht an dieser Stelle zum Opfer gefallen und nur ansatzweise erkennbar ist. Gegen die Lesung des Buchstabens nach εξ in Z. 17 als υ spricht die Rechtskrümmung der senkrechten Haste, die völlig untypisch für das υ dieser Hand ist; das Zeichen erschiene, als υ gelesen, allzu ungelenk im Kontext des Schriftbildes. Geht man davon aus, dass der linke schräge Strich des mutmaßlichen υ noch zum vorangehenden ξ gehört, kann man stattdessen ein ε lesen, womit eine Form von ἐξεῖναι nun ohne weiteres möglich ist. Schließlich kann statt π]ρογεγραμμένον in Z. 18 problemlos π]ρογεγραμμένων gelesen werden (vgl. die Schreibweise von -ων- in τῶν [Z. 6] und Ἀπολλωνίου [Z. 12]). Ausgehend von diesen Änderungen kommt man für die Zeilen 17–18 zu folgender Rekonstruktion:

![]()

„Und sie verordneten, dass es niemandem erlaubt sei, unter irgendeinem Vorwand wegen der oben aufgeführten Sachverhalte rechtliche Schritte einzuleiten.“

Es handelt sich um eine Formel, die aus Dokumenten privatrechtlicher Natur bekannt ist, in denen sie den Verzicht auf Rechtsansprüche signalisiert (vgl. z.B. P.Adler 3, P.Dion. 28–31 und 35, P.Eleph. 3 und 4, P.Hib. I 96). ὑπέρ, das im Kontext von Rechtsgeschäften typischerweise „im Interesse von/stellvertretend für“ bedeutet, wird hier anstelle von περί in der Bedeutung „wegen, betreffs“ benutzt, wie beispielsweise auch in der Verzichtserklärung BGU VI 1249 (vgl. Mayser, Grammatik II 2, 450–453). Es bleibt lediglich zu überlegen, ob statt ἐξεῖναι nicht ἐξναι geschrieben wurde, wobei ε für ει vor Konsonant ein eher selten belegtes Phänomen ist (vgl. Mayser, Grammatik I 1, 54f.). Möglicherweise sind auch an dieser Stelle Abschabungen und Einkerbungen dafür verantwortlich, dass der Buchstabe mehr Querhasten zu haben scheint, als tatsächlich der Fall ist. Dass hier eine Form von ἐξεῖναι steht, was der Herausgeber noch verworfen hatte, dürfte nunmehr unzweifelhaft sein.

Es erscheint in dieser Darstellung des königlichen Prostagmas, als sei der Umfang der Generalamnestie gegenüber dem des unmittelbaren Vorgängers — des Indulgenzdekrets des Ptolemaios V. Epiphanes von 186 v. Chr. (P.Köln VII 313) — erweitert oder zumindest bekräftigend erläutert worden. Glaubt man der Formulierung des Petenten, verzichteten die Königin und der König nicht nur selbst auf eine Ahndung von Vergehen der zuvor aufgelisteten Arten (ἁμαρτήματα etc., Z.15f.), sondern untersagten auch Klagen von Privatpersonen und die Weiterverfolgung vor dem Stichtag erhobener Ansprüche (ἐνκλήματα, Z. 15) durch selbige. Es mag sein, dass es sich hierbei um eine verzerrte Wiedergabe einer Habeas-Corpus-Akte handelt, wie sie in P.Köln VII 313 B 10–20 und in den Philanthropa von 118 v. Chr. (P.Tebt. I 5, 255–264) enthalten ist und die lediglich amtliche Willkür verbot, Gerichtsverfahren aber keinesfalls ausschloss. Selbst gesetzt den Fall, dass der Inhalt des Prostagmas korrekt wiedergegeben ist, ist es ungewiss, ob die Amnestie im Fall unseres Petenten griff, denn die Schilderung des Streitgegenstandes am Beginn der Petition entzieht sich einer Rekonstruktion.

Eva KÄPPEL

The final section of P.Oslo III contains thirteen ‘Short Texts and Fragments’ (nos. 166–178), first published by S. Eitrem and L. Amundsen in 1936. Subsequent review of this section led to three identifications, namely: no. 168 = Menander, Dyscolus 766–773 (J. Lenaerts,Pap. Brux. XIII 7); no. 170 = Xen. Ap. 25 (M. Gronewald,ZPE 86, 1991, 3–4); no. 177 = chreiai (J. Lenaerts,CdE 49 [1974], 122; I. Gallo,Frammenti biografici da papiri, 363; R. F. Hock, E. N. O’Neil, The Chreia and Ancient Rhetoric, II, 24–26). No. 175 (inv. 904) and no. 176 (inv. 971), both from Oxyrhynchus (see http://ub-fmserver.uio.no/Acquisition.html, last accessed on 09.10.2016), can now be classified with a fair degree of certainty as, respectively, documentary and literary.

The text on the verso of P.Oslo III 175 (unpublished documentary piece on the recto) was tentatively interpreted as ‘literary’ by S. Eitrem and L. Amundsen, who hypothesized an epic dative ὄρεσ̣[σι in l. 7. The σ, which is clearly visible, seems in fact to be followed by a triangular letter. The word ἐγλα̣[ (ε̣γλ̣[ ed. pr.) in l. 5 suggests the assimilated form ἐγλα̣[(μ)β- for ἐκλαμβάνω, common in documentary papyri from this period: see F. Gignac,A Grammar of the Greek Papyri of the Roman and Byzantine periods, I, Milan 1976, 175.

P.Oslo III 176 (verso is blank) was described as a ‘small fragment which according to the handwriting may be literary’ and dated to the second century AD. Indeed, the hand recalls that of Oxyrhynchus scribe #A7 (cf. the upright of τ with its foot hooked to the left at l. 2 with P.Oxy. XXII 2313, Archilochus, II AD, e.g. fr. 9.1 τοι, 21.1 τις W2) and the London Hyperides (P.Lond. Lit. 132, first half of the second century AD, cf. e.g. col. XXIX 5 εξετασωμεν and XX.13 εξετασωσιν with l. 5 εξ[). At l. 1, the editors’ ινδαλε[ does not produce sense. The round letter before the break is in fact θ (contrast the much higher horizontal bar of ε in 5 εξ[), which yields ἰνδαλθ̣[, aorist form of ἰνδάλλομαι ‘to appear’ or, construed with the dative, ‘resemble’, see LfrgE, s.v. ἰνδάλλομαι (R. Führer), M. Campbell on A.R. 3.453. The verb does not occur in documentary papyri. Aorist forms are attested exclusively in poetry and occur in Lyc. 597 κύκνοισι<ν> ἰνδαλθέντες (Diomedes’ comrades transforming into birds ‘resembling swans’), 961 ἰνδαλθεὶς κυνί (the river-god Crimisus seducing Aegesta ‘in the guise of a dog’), and Max.Astr. 163 ἰνδαλθῆι κερόεσσα (the Moon ‘appearing’ in Taurus); cf. also the substantive ἰνδαλμόν ‘image’ in P.Ross.Georg. I 11.29 ὦ̣ρ[σ]ε (Dionysus) δ[έ] ο[ἱ (Lycurgus) μ]α̣ν̣[ί]ην, ὀ̣φίων δ’ ἰνδαλμὸν̣ [ἔ]χ̣ε̣υ̣[ε]ν (‘ghostly vision of snakes’); ἴνδαλμα = εἴδωλον in Man. 6.569–570 οἱ μὲν (stars) γάρ τ’ ὀλοοὶ κῆρας καὶ δείματ’ ἄγουσι<ν> / εἰδώλων τε βροτοῖς ἰνδάλματα δαίμοσιν ἶσα.

Marco PERALE

Bei SB VIII 9785 (Herk. unbek., 5.–6. Jh.) handelt es sich um eine Pachtzinsquittung, die ursprünglich aus der privaten Sammlung von Hugo Ibscher stammt (P.Ibscher 17) und von diesem in den Jahren 1937 und 1938 Papyri in Kairo erworben wurde [17]. Im Jahr 1962 gelangte der Text in den Besitz der Berliner Papyrussammlung (P.Berol. 18142). Ediert wurde er zusammen mit sechs weiteren Papyri aus Ibschers Sammlung von Wolfgang Müller[18]. Dieser konnte fünf der sieben publizierten Stücke dem Arsinoites zuweisen (Nr. 1 = SB VIII 9779 = P.Zen. Pestm. 43 = BGU X 1993 [Ars.]; Nr. 2 = SB 9780 = P.Zen. Pestm. 41 [Ars.], Nr. 4 = SB VIII 9782 [Ars.]; Nr. 5 = SB VIII 9783 [Euhemeria] u. Nr. 6 = SB VIII 9784 [Ars.]). Die Herkunft von Nr. 3 = SB 9781 = BGU X 1996 und Nr. 7 = SB VIII 9785 musste hingegen offenbleiben, wenngleich der Editor zumindest hinsichtlich Nr. 7 die Vermutung äußerte: „Der Papyrus stammt vielleicht aus dem Hermopolites (Vgl. z.B. P.Lond. V 1781; III 1051, 1060 u.ä.)“ (S. 84). Das Formular des Textes lässt in der Tat Rückschlüsse auf die Herkunft zu: Einerseits ist festzustellen, dass die nächste Parallele zur Formulierung λογίζομαί σ[οι] ἀναμφιβόλως καὶ εἰς σὴν | ἀσφάλειαν πεπ̣οίημαι τοῦτο τὸ ἐντάγιον κτλ. (Z. 5–6), und zwar SPP III 373 (Z. 2–3: λογίζομαι σοὶ εἰς̣ [- - - τήν] | ἀσφάλειαν πεποίημαι), aus dem Hermopolites stammt. Die alleinige Wendung λογίζομαι σοί weisen im übrigen mehrheitlich Quittungen aus dem Hermopolites auf[19], obwohl dieser Wortgebrauch grundsätzlich auch in südlicheren Regionen zu beobachten ist[20]. Andererseits entspricht der Beginn des Textes (Ζ. 1: † παρ(ὰ) Θεοφίλου Κολλο̣ύθου Χριστοδώρῳ ἀδελφῷ. δέδωκας κτλ.) dem typischen hermopolitischen Einleitungsformular (παρά + Genitiv + δέδωκας) [21]. Somit liegt die Vermutung nahe, dass die Pachtzinsquittung SB VIII 9785 im Hermopolites ausgestellt wurde.

Kerstin SÄNGER-BÖHM

P.Mich. II 123 ist eine ἀναγραφή, die aus dem Kontext des Grapheions von Tebtynis (Ars.) stammt und zu dem Archiv des Kronion, Sohn des Apion, dem Leiter des Grapheions, gehört [22]. Dem Charakter einer ἀναγραφή entsprechend werden in P.Mich. II 123 die Urkunden, die in dem Grapheion von Tebtynis aufgesetzt wurden, mit kurzen Angaben zu ihrem Typ, den Urkundsparteien, dem Gegenstand oder Wert des Rechtsgeschäftes und der Höhe der veranschlagten Schreibgebühr (γραμματικόν) in chronologischer Reihung aufgelistet. Der dokumentierte Zeitraum umfasst das sechste Regierungsjahr des Kaisers Claudius (45/6 n. Chr.). Der auf dem Rekto in Kol. XXII, 44 anzutreffende Eintrag wurde in der ed. pr. mit [συ]νγρ(αφή) πλήθο<υ>ς ἀπολυσ[ίμων - ] wiedergegeben, womit es sich um einen unspezifischen Vertrag handeln würde [23], als dessen Bezugspunkt die Versammlung von Personen genannt wird, die von irgendwelchen Pflichten befreit waren [24]. Die Lesung [συ]νγρ(αφή) verwundert allerdings angesichts paralleler Einträge, die im Zusammenhang mit dem πλῆθος einer Vereinigung immer nur eine Urkunde nennen, die als χειρογραφία, also als „handschriftliche Erklärung“[25], bezeichnet wird [26]. Eine derartige Auflösung würde auch zu dem Duktus am Beginn von Z. 44 passen, der sich anhand einer online verfügbaren Abbildung von Kol. XXII überprüfen lässt [27]: Das Erste, was direkt nach der Lücke erkennbar ist, ist eine kurze Längshaste [28], auf welche γ und das hochgestellte ρ folgen. Diese Längshaste würde nicht nur zu dem Ende eines ν, sondern in dieser Hand auch zu dem Abschluss eines oben nicht geschlossenen ο passen; siehe etwa die anschließend in πλήθο<υ>ς und ἀπολυσ[ίμων dokumentierte Schreibweise, die Rekto, Kol. VI, 25 und P.Mich. II 124 Rekto, Kol. II, 15[29] auch in χιρογραφία ( l. χειρογραφία) entgegentritt. Im übrigen scheint auch die Kürze der Längshaste eher für ο zu sprechen, denn ν weist in P.Mich. II 123 für gewöhnlich längere Hasten auf. Somit sei für P.Mich. II 123 Rekto, Kol. XXII, 44 die Lesung [χιρ]ο̣γρ(αφία) (l. χειρογραφία) πλήθο<υ>ς ἀπολυσ[ίμων - ] vorgeschlagen.

Abschließend soll nicht unerwähnt bleiben, dass uns in P.Mich. V 244 (Ars., 43 n. Chr.) die Satzung einer Vereinigung erhalten ist, die von ἀπολύσιμοι gebildet wurde, die der οὐσία des Claudius zugewiesen waren. Da auch dieses Dokument zu dem Archiv des Kronion zu zählen ist [30] und in zeitlicher Nähe zu unserer ἀναγραφή steht, würde es naheliegen, die in P.Mich. II 123 Rekto, Kol. XXII, 44 bezeugten ἀπολύσιμοι, die im Zusammenhang mit einer χειρογραφία auch Rekto, Kol. III 40 und VIII 26 bezeugt sind, mit jenen von P.Mich. V 244 zu identifizieren [31]. Letztere Urkunde wird auf dem Verso als χιρογρ( ) (l. χειρογρ( )) bezeichnet, was man als weiteren Hinweis darauf erachten könnte, dass in P.Mich. II 123, Kol. XXII, 44 keine συγγραφή, sondern eine χειρογραφία registriert wurde [32].

Patrick SÄNGER

[1] Zu dem überaus häufigen γράφω mit ὅτι / διότι vgl. E. Mayser, Grammatik der griechischen Papyri aus der Ptolemäerzeit mit Einschluss der gleichzeitigen Ostraka und der in Ägypten verfassten Inschriften , Berlin, Leipzig 1926, II 1, 313.

[2] Vgl. Mayser (s. o. Anm. 1) 348–349.

[3] Vgl. Mayser (s. o. Anm. 1) 351.

[4] The archive should be added to the recent survey of K. Vandorpe, W. Clarysse, H. Verreth, Graeco-Roman archives from the Fayum , Collectanea Hellenistica 6 (2015). It has been integrated in Trismegistos as no. 574. Perhaps BGU VII 1591 (another receipt for the weavers’ tax) and 1564, 1572, 1602, 1615, 1616 also belong to the same find, as is suggested also by their inventory numbers (with the exception of 1615).

[5] The suggestion in BGU VII 1615, note on l. 13 to identify [Π]ε[ε]θ ̣ ̣ with Πεεβ( ) in P.Lond. II 257.126 is excluded.

[6] I have not included the proposal to read πάλαι Στρ̣ατί̣π̣π̣ο̣υ̣ in BGU XVIII 2747 (Herakleopolites). The limited geographical spread of the name confirms the doubts of A. Verhoogt in BL XII 31. The reading Στρατ̣ί̣π̣π̣ου in P.Oxy. LV 3787.19 should be corrrected to Στρατ[ονίκ]ου (checked on the original in the Sackler library; the minimal traces in the middle are all but illegible).

[7] Titan is himself the son of Nemesion and he is more than 60 (ὑπερετής) in AD 51 (P.Sijpesteijn 26.87 and 92).

[8] W. Clarysse, A demotic self-dedication to Anubis, Enchoria 16 (1988), pp. 7–10.

[9] Outside Egypt the name also disappears after the Hellenistic period. The only Roman example in LGPN is IG IX.2 544.19 (AD 41). The eponymous priest Alexarchos, son of Stratippos, in Sardeis is dated to the early first century BC by H. Malay, I. Manisa Museum no. 11.

[10] Cf. A. Hanson, Pap.Congr. XXV, Ann Arbor 2010, pp. 310–311.

[11] The name of the maternal grandfather may be supplied as Ἀλε[ξ]ᾶς.

[12] For temples as house owners, see W. Otto, Priester und Tempel, Leipzig, Berlin 1905, 288–290.

[13] Plus the symbol for μη(τρός) after the chi. I describe it here as a “symbol”, because as far as I can see, it is “rapidly made that the individual letters of which they are composed are no longer recognizable”, see H. C. Youtie, The Textual Criticism of Documentary Papyri. Prolegomena, London 21974, 49 and see also note 15 below.

[14]

Searching for Πετεχ- in Trismegistos name search

(http://www.trismegistos.org/nam/

search.php) will give the above-mentioned suggestions and many

others.

[15]

The second image does not allow more than these two suggestions,

but a look at the original would solve the problem, see the images

at: http://brbl-legacy.library.yale.edu/papyrus/

oneSET.asp?pid=301 and

http://brbl-legacy.library.yale.edu/papyrus/oneSET.asp?pid=303. For

the mothers’ names see s.v. in NB and cf. also their records by

TM-namID 1262: www.trismegistos.org/name/1262 for Θαμουνις,

TM-namID 1264 www.trismegistos.org/

name/1264 for Ταμουθις and TM-namID 6050

www.trismegistos.org/name/6050 for Ταμύσθα.

[16] Lautinas is the youngest member of this family, the last keeper of its archive and the person to whom most of the tax receipts in this archive were addressed , see the introduction to these texts pp. 1–3 of the volume and the respective texts, Montevecchi, La papirologia, 1988, 577 no. 20 and the description of the archive in TM_archID 129 www.trismegistos.org/archive/129.

[17] So W. Müller, Papyri aus der Sammlung Ibscher, JJP 13 (1961) 75–85, hier 75.

[18] Siehe Müller, op. cit.

[19] BGU XVII 2715 (Herm., 6. Jh.); P.Herm. 70 (Herm., 501); 71 (Herm., 502); 72 (Herm., 507); 78 (Herm., 498) und 82 (Herm., 507).

[20] So wie in zwei Ostraka aus Apollinopolis Magna; vgl. J. Gascou, Ostraca byzantins d’Edfou et d’autres provenances, TMByz 16 (2010) 367–369, Nr. 6 (= O.EdfouCopte 91) sowie 369–371, Nr. 7. Zu Varianten mit λογίζομαι siehe die Nr. 6, Komm. zu Z. 7–8.

[21] Ich danke N. Gonis für diesen Hinweis.

[22] Zu dem Archiv siehe zusammenfassend B. Van Beek, Kronion son of Apion, head of the grapheion of Tebtynis, in: Trismegistos Archives, Stand: ArchID 93. Version 2 (2013), http://www.trismegistos.org/arch/archives/pdf/93.pdf (abgerufen am 15. November 2016).

[23] Zu συγγραφή als der allgemeinen technischen Bezeichnung für „Vertrag“ oder „Urkunde“ siehe H. J. Wolff, DasRecht der griechischen Papyri Ägyptens in der Zeit derPtolemaeer und des Prinzipats, Zweiter Band: Organisation und Kontrolle des privaten Rechtsverkehrs (HdAW X 5, 2), München 1978, 84; S. Lippert, Einführung in die altägyptische Rechtsgeschichte (Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie 5), Berlin 22012, 141.

[24] Zu der Wortbedeutung von ἀπολύσιμος siehe Preisigke, WB I 188 s. v.; LSJ9 208 s. v.; A. E. R. Boak, P.Mich. V 244, Einleitung, S. 100–101.

[25] Siehe Preisigke, WB 781 s. v.; LSJ9 1985 s. v.

[26] P.Mich. II 123 Rekto, Kol. III, 41: χιρογρ(αφία) (l. χειρογραφία) πλήθους γερδίων; Kol. VI, 25: χιρογραφία (l. χειρογραφία) πλήθο(υς) ἐριοπολῶν (l. ἐριοπωλῶν). Siehe auch die ebenfalls zu dem Archiv des Kronion gehörende ἀναγραφή P.Mich. II 124 (46–49 n. Chr.), wo Rekto, Kol. II, 15 der Eintrag χιρογρ(αφία) (l. χειρογραφία) πλήθο<υ>ς ἐριοπολῶ(ν) (l. ἐριοπωλῶν) begegnet.

[27]

http://quod.lib.umich.edu/a/apis/x-3216/966R6_1.TIF?from=index;lasttype=boolean;

lastview=reslist;resnum=24;size=50;sort=apis_inv;start=1;subview=detail;view=entry;rgn1=apis_inv;select1=regex;q1=966

(abgerufen am 15. November 2016).

[28] Diesen Eindruck hat Brendan Haug, der Archivar der Papyrussammlung der University of Michigan, nach Autopsie des Originals bestätigt.

[29] Zu diesem Beleg siehe oben Anm. 26.

[30] Siehe A. E. R. Boak, The Organization of Gilds in Greco-Roman Egypt, TAPhA 68 (1937) 212–220, hier 212.

[31] So auch die Vermutung von A. E. R. Boak, P.Mich. V 244, Einleitung, S. 101.

[32] Diese Überlegung würde auf dem Verso von P.Mich. V 244 freilich die Ergänzung χιρογρ(αφία) (l. χειρογραφία) nach sich ziehen, was sich gegen Wolff, Recht (s. o. Anm. 23) 128 und K. H. Schnöckel, Ägyptische Vereine in der frühen Prinzipatszeit. Eine Studie über sechs Vereinssatzungen (Papyri Michigan 243–248) (Xenia. Konstanzer Althistorische Vorträge und Forschungen 48), Konstanz 2006, 21–22 richten würde, die hier — basierend auf der ed. pr. — χιρόγρ(αφον) (l. χειρόγραφον) aufgelöst haben. Zu dieser Problematik und einer genaueren Definition der in P.Mich. II 123 und 124 im Zusammenhang mit Vereinigungen genannten χειρογραφίαι siehe demnächst ausführlich P. Sänger,Registrierung und Beurkundung von νόμοι im Grapheion von Tebtynis, in: A. Jördens, U. Yiftach-Firanko (Hrsg.), Accounts and Bookkeeping in the Ancient World: Question of Structure, Schwetzingen, 22.–24. Sept. 2016 (Legal Documents in Ancient Societies 8), in Vorbereitung.