BEMERKUNGEN ZU PAPYRI XXVIII

<Korr. Tyche>

P.Oxy. XVIII 2207 is a bare list of toponyms with some duplicates and deletions. Its hand was assigned broadly to the sixth century by the editors, but it can more specifically be placed near the turn of the seventh century (‘late sixth or early seventh century’). As the editors saw, the villages and hamlets listed connect the document with the Apion estate. Most are known from other papyri to have been centres of the estate’s administrative districts called prostasiai[1]. I reedit the text here with some corrections, incorporating those previously proposed. The writing runs along the fibres, and the back is blank. The document is virtually complete and has an ample lower margin [2].

1 + Πε̣τ̣ρωνίο̣υ̣: Πετρωνί[ου] ed. princ. (cross not reported).

2–3 Νέου | Ταμπετι. The editors erroneously considered these two entries to form one toponym, Νέον Ταμπετι (cf. also Index V (b) p. 204), despite the fact that they are written over two separate lines; for their differentiation, see BL VIII 255.

8 Ἀρτοκοπίου: Ἀρτοκοπίο(υ) ed. princ.

11 Πια’α pap. (apostrophe not reported in ed. princ.). For other examples of apostrophes between vowels, see F. T. Gignac, A Grammar of the Greek Papyri of the Roman and Byzantine Periods. Vol. 1: Phonology (Milano 1976) 165.

21 [Θαή]ϲιοϲ: [Κτή]ϲιοϲ ed. princ. Although both toponyms are known Apionic hamlets, [Θαή]ϲιοϲ is a likelier supplement, since it is well attested as a centre of a prostasia (P.Oxy. VIII 1147.19, XVI 2007.4), whereas no pronoetes has ever occurred in connection with Κτῆϲιϲ. The genitive of the latter toponym, moreover, is always Κτήϲεωϲ.

22 [Εὐα]γ̣γελίου: [Εὐαγ]γελίου ed. princ.

23 [Παγγ]ου̣λε̣ε̣ίου: [ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣]οϲλε̣ν̣δου ed. princ. The second epsilon is of the small variety, with a short upper diagonal stroke, like that in [Εὐα]γ̣γελίου (22) and Φατεμητ (32).

24 [Ταρο]υ̣θίνου: [ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣] ̣θίνου ed. princ. The toponym is repeated and then deleted in line 28. The restoration was tentatively proposed by P. Pruneti, I centri abitati dell’Ossirinchite (Firenze 1981) 229[3], but was not recorded in BL.

25 [Ϲκυτα]λ̣ίτιδοϲ: pace the editors, who print [ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣]λ̣ίτιδοϲ but state that ‘the name is probably not Ϲκυταλίτιδοϲ, as this occurs in l. 31’. There is, however, no other possible candidate, and the toponym fits space and trace perfectly. The repetition is presumably accidental, or the scribe forgot to cross out one of the instances (as he does for Tarouthinou in 28 ~ 24).

26 ⟦Π̣έρα̣ Μ̣ε̣ρμέρθων⟧: ⟦Ερ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣τ̣τ̣ερθωνί̣ου⟧ ed. princ.: ⟦Ἔρ̣ω̣τ̣ο̣ϲ̣ κ̣(αὶ) Ὀρθωνίου⟧ BL VI 106. The reading of Μ̣ε̣ρμέρθων is due to Dieter Hagedorn (as communicated to Nikolaos Gonis in 2004), that of Π̣έρα̣ to me. There is nothing after ων apart from the extension of the deletion strokes. This Apionic locality ‘opposite Mermertha’ in the south of the nome has only been attested twice (P.Oxy. XIX 2244.8, LXXVII 5123.8, 23).

27 Μεγάλου Μούχεωϲ BL VIII 255: Μεγάλου Ῥούχεωϲ ed. princ.

30 ⟦Πουϲεμπόϋϲ⟧: ⟦Πευϲέμπουϲ⟧ ed. princ.

32 Φατεμητ’ pap. I take a hook descending from the end of the bar of tau to be an apostrophe; cf. J. R. Rea, P.Oxy. LXIII 4391.1 n.: ‘Sometimes this name appears with a mark like an apostrophe which is used at the end of indeclinable Egyptian names … and which has often [incorrectly] been taken for a sign of abbreviation’ (with reference to GMAW2 p. 11).

768. P.Oxy. XVI 2031

This document, assigned to the late sixth or early seventh century, is an account of money payments made to overseers (pronoetai) of various districts of the Apion estate. In line 8 the editors print προν(οητῇ) Α̣ ̣ ̣κ ̣τ̣ίου. The only viable candidate for the toponym is Ἀρτοκοπίου, an Apionic hamlet attested in P.Iand. III 51.18 (VI) and P.Oxy. XVIII 2207.8 (reedited above, Korr.Tyche 767). The original is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, but its ‘inv. no. [is] not known’, and it was ‘not yet found’ in 1971 when the location-list of Oxyrhynchus papyri was being compiled [4]. As a result, there is no black-and-white archival photograph of the papyrus in the Papyrology Rooms at Oxford to verify the reading. An unpublished document in the Oxyrhynchus collection confirms that this hamlet was the centre of a prostasia.

Amin BENAISSA

Early 2014 I have put online, in the framework of Trismegistos, a small database of ghostnames found in papyrus editions [5]. For each ghostname I identify the sources where it was read and the publication where the reading was corrected. The database also contains a typology of errors, such as errors of indexing (e.g. faulty reconstruction of nominatives), wrong supplements, wrong word divisions, errors and/or corrections by the ancient scribes, confusion between anthroponyms and toponyms, or between individual letters (e.g. alpha and lambda) or groups of letters (e.g. lambda-iota and ny).

Strictly speaking ghostnames are non-existing names, which would then completely disappear once corrected. In a number of cases, however, the names are in fact attested in other regions (in inscriptions for instance) or in completely different periods (a name such as Eusebios is common in the Christian period, but impossible in Ptolemaic times).

Some ghostnames started to lead a life of their own once they were incorporated in the papyrological lexica of Preisigke and Foraboschi [6]. Thus the many impossible names read by Brunet de Presle in his edition of the Paris papyri in 1836 were included in Preisigke’s Namenbuch because in 1920 the long name list P.Par. 5 was not yet republished by Wilcken in UPZ 180. Brunet de Presle had to work without parallels and in 1836 the transcription system of Egyptian names in the Greek alphabet was not known at all. The names read by him in P.Par. 5, listed in the Namenbuch, became a starting point for more errors by text editors confronted with a problematical passage.

The following examples of ghostnames occurring in more than one text, are usually introduced in the later editions with a reference to our onomastica. In several instances the original was damaged or could not be checked, so that an exceptional name could not be eliminated with certainty. All we can do in such cases is warn editors that they should not take unique examples as a model when struggling with a difficult passage.

The ghostname Amaron is listed in both the Namenbuch and the Onomasticon. In BGU VII 1678.7 it is the result of a wrong word division by the editor, who reads διʼ Ἀμάρων[ο]ς̣ instead of διὰ Μάρων[ο]ς̣, with the name Maron, which is common in the Arsinoites.

The name Amaron seems, however, to be attested in two other passages, which are both suspect:

SB I 4489, dated AD 584, was published by Wessely without a photograph. It was republished by P. Jernstedt in VDI 40 (1952) 201–209, who added a fragment in Tbilisi; in BL VII 184 a complete reedition in SB XVIII is announced, which, however, never appeared. Ἀμάρων functions as a patronymic in l. 17 of the Paris fragment; though there are no dots, the reading needs to be checked. This is not an easy task because Wessely does not give a plate nor an inventory number.

In O.Amst. 81.3 the editors read [ὀ]νό(ματος) Ἀμ̣ά̣ρω̣(νος) Ἀπίωνο(ς). The dotted letters show his uncertainty and the reading is almost certainly erroneous (again no plate is available).

The name Anompis is listed in Preisigke’s Namenbuch, with reference to P.Giss. I 43.16–17 (= P.Alex.Giss. 14) and P.Ryl. II 217.108. In both cases the papyrus has the genitive Ἀνομπεως, which should be linked to a nominative Ἀνεμπευς/Ἀνομπευς, corresponding to the well-known Egyptian name Ỉnpw-ỉw “Anoubis has come” (Demotisches Namenbuch, p. 69). The faulty indexation by the editors was adopted in the onomastica.

The name Kallapis is listed in both the Namenbuch and the Onomasticon. The latter’s reference to O.Mich. I 5.2 was, however, corrected in ZPE 186 (2013) 245–246, where I proposed Ἀπολλώνιος instead of Κ̣α̣λλαπις. The Namenbuch refers to P.Lond. II 369.12 (p. 265): Καλλα̣π̣ι̣ς. The editor’s doubts are clear from the dotted letters. The text is written in a cursive professional hand with many ligatures. I do not dare to propose a new reading but the reading Καλλα̣π̣ι̣ς needs to be revised on the original. Κραλης in l. 20 of the same text should be read Κιαλης: the iota is written in one stroke with the preceding alpha and therefore presents a small hook at the top. Kialês is a common name, corresponding to Coptic ϭⲁⲗⲉ “lame”, Krales is a ghostname.

P.Graux II 15 is a list of persons with names and patronymics. In ll. 10–11 the editor reads:

Neither Kanin[ios] nor Moros are real ghostnames, but they are both problematical: the former could indeed render the Latin name Caninius (cf. Marcus Caninius in O.Claud. II 363), the latter might be a variant of the well-known name Μῶρος, but two anomalies in two lines led me to have a closer look at the photograph (pl. VIII). There it is possible to read:

Apparently two brothers, sons of Spartakos, pay (or receive) an amount of grain on the same day. The editor was tricked because all other persons in the list receive one separate line each for their name and patronymic, whereas here the two brothers are mentioned together.

The name Mystharios is listed in the Onomasticon, p. 200 with reference to SB VI 9008.3: Πετέρμουθ(ις) τοῦ Κρονίω(νος) τοῦ Μυσθ(αρίου). The abbreviated papponymic should be expanded to a common name, e.g. Μυσθ(αρίωνος) or Μυσθ(ᾶτος), rather than creating a new name.

Similarly in CPR VIII 1.75 Ἐνατιω( ) δι(ὰ) Μυσθ[αρί]ο̣(υ) the supplement is too uncertain and it is better to read δι(ὰ) Μυσθ[ ̣ ̣ ̣]ο̣( ) or even δι(ὰ) Μυσθ[αρί]ω̣(νος), since Mysthariôn is a common name.

In SPP IV, pp. 62–78 verso, l. 350 Wessely reads δ[οῦλ]οι M[υσθα]ρ̣ί̣ου [ἀδελφῆς Νικ]άνορ[ος] το[ῦ καὶ Πάππου] τ[οῦ Ἡρακ]λ̣είδ[ου]. He indexes the name as a genitive Μυσθαρίου, and one could reconstruct a feminine nominative Μυσθάριον. This name is, however, nowhere attested and it is therefore more likely that the reading and supplement are erroneous. It is better not to supply a name here and to present only what remains on the papyrus: Μ[ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣]ρ̣̣ι̣ου.

The only reference in the Namenbuch refers to P.Lond. I 131.174 (p. 175), and here the reading Παχνουτις is clear on the British Library microfilm. Pachnoutis is therefore not a ghostname, but it is extremely rare, as the other supposed examples are erroneous.

The name Παχνουθιος in the Onomasticon is based on an error in the index of SB V 7531. The edition in the Sammelbuch and in P.Ross.Georg. V 70.7 reads a banal Παπνο̣ύ[θ]ιο(ς) (genitive).

P.Col. VII 153.47 is not included in the onomastica. The editor reads Αὐρήλ̣ιος Π̣α̣χ̣νοῦτις Πιῶν(ος). The dots under the first three letters of the name indicate uncertainty. In my opinion it is possible to read Π̣ά̣π̣νουτις, when one takes into consideration that the upper part of the fragment is slightly displaced to the left (as is clear from the left leg of the ny).

The name Pamoni(o)s is listed in the Namenbuch for two papyri from Hermonthis, P.Lips. I 19.9 (= Chrest.Mitt. 276): [Π]αμώνιος and P.Lips. I 97 col. 7.22: Παμ̣ώ̣ν(ι). Preisigke considers it a variant of Pamouni(o)s, but Greek Ammon names (usually with double my) and Egyptian Amoun names are normally kept well apart.

In both cases the name is damaged. The first text is lost since 1978 and the reading cannot be checked, but the supplement of an initial pi is not necessary: one could read the name as Ἀμώνιος, with a single my. In P.Lips. I 97 Mitteis reads Παμ̣ώ̣ν(ι) Π̣ε̣κύσιος Μαρκ( ). Papponymics are uncommon in this long text and the transition from the name to the patronymic is problematical from a palaeographical point of view (the abbreviation is unusual and the initial pi of the patronymic is dubious). I read Παμ̣ω̣ντ̣ε̣κύσιος, a variant form of Παμοντέσκυσις. This name “the one of Montou the Nubian” is typical of Hermonthis, see O.Heid. 225.2 n.

Another example, tentatively read as [Π]α̣μ̣ώ̣[νιο]ς by P. J. Sijpesteijn in P.Wisc. Ι 14.13 was corrected by D. Hagedorn, ZPE 1 (1967) 149 and never entered in the lexica.

In P.Mil.Vogl. IV 215.4 (Tebtynis; AD 169) a certain [Π]ατάρυτις προστάτης receives the substantial sum of 100 dr. The editor, D. Foraboschi, finds the same person in P.Mil.Vogl. II 110.14, where Paoletti had wrongly read Παταρε̣υ̣τι and reconstructed a nominative Παταρεύς. A homonymous phrontistes occurs in the same archive in P.Mil.Vogl. I 28.57 (AD 162–163) (Παταρύτι φροντιστῆ̣, listed as Παταρῦς in the Onomasticon, p. 238) and VII 307.102 and 114 (dated generally to the second century AD). Though Foraboschi rightly reads the name in the dative as Παταρυτι, he indexes it under the lemma Παταρεύς (P.Mil.Vogl. 7, p. 106). The homonymous person who receives two artabas for the epispora in P.Mil.Vogl. VII 303.126 is no doubt the same man, though he bears no title. I propose to correct here too Παταρευτ(ι) into Παταρυτ(ι), dative of Παταρυτις. On the plate in the volume there is no trace of the epsilon. The name recurs in a fragmentary context in P.Mil.Vogl. VI 276.4, where the editor reads a genitive Π̣αταρύτεω[ς], but reconstructs a faulty nominative Παταρύς (instead of Παταρύτις), with a reference to the edition of Vogliano.

The name Patarytis is typical of the Roman Arsinoites, and perhaps even of Tebtynis (though perhaps all references above refer to the same person). It is also found in SB I 5124.139 and 385 (AD 193), the famous Charta Borgiana, in SB XIV 11486 d.6 (AD 213; written as Παταρύτης), both listing people from Tebtynis, and in P.Fouad 68.6 (AD 180). The last text comes from the Fayum and Tebtynis is not an unlikely provenance, given the appearance of several Kronos names.

Παταρωτ, which recurs several times in the Petaus archive, from the other side of the Fayum oasis (P.Petaus 100; 116; 117) is no doubt a variant of the same name, of which the etymology remains unknown.

The ghostname Patareus crops up again in P. Oxy. XLV 3245.12, with explicit reference to the parallels in P.Mil.Vogl. The alternative proposed by the editor to read here the ethnic Πα̣τα̣ρ̣[έα] is clearly preferable to the non-existing Egyptian name Πα̣τα̣ρ̣ε̣[υτα].

The name Σεμθοημοις is attested four times in an early Roman papyrus dealing with the Herakleopolite nome (P.Oxy. XXIV 2412.113, 114, 161 and 163). The clippings below show that the editors mixed up pi and eta. Only in l. 161 would eta be a possible reading; elsewhere pi is clear. Moreover the name Semthopmois, “Semtheus the lion”, is attested in the Herakleopolite nome (P.Teb. III 876.72; P.Oxy. LVIII 3928.4 with the variant form Σεφθομοις).

The name Σισους is listed in the Namenbuch and the Onomasticon with reference to P.Lond. II 258.26 (p. 29) and P.Bad. II 42 respectively. In the former case the microfilm of the British Library allows to correct Σισους into Σισοις. The iota is apparently surmounted by a short stroke, which may derive from the usual trema above this letter. In P.Bad. II 42.20 the first letter is damaged and I propose to read Ε̣ἰσους. This could be an itacistic variant of Isous, a rather rare name, but an acceptable derivation from Isis.

The name Sisous turns up again in PUG III 114.4, but here again Σισοιτος is preferable to Σισουτος, as I had already suggested to the editor (see note on l. 4). The ypsilon in this hand does not have a V form but is always written as Y. The apparent parallel πυροῦ in ll. 9, 10, 11 and 13 should in each case be read as πυρῶν in the plural, as is normal in Ptolemaic texts and the high-rising ny typical of the period [7].

Willy CLARYSSE

Ce document est la partie gauche d’une lettre d’époque tardive (VIe ou VIIe s.), le début de l’époque arabe n’étant pas, à mon avis, à exclure. L’édition a été améliorée par L. Berkes et surtout par D. Hagedorn[8]. D’après le verso, la lettre est adressée à un évêque anonyme par son νοτάριος Isakos. Du fait des mutilations, peut-être sous-évaluées par les éd. [9], le sens est difficile à saisir en détail. Cependant, avec sa lecture de la l. 12, Hagedorn a vu qu’un des objets de la lettre était le sort de 450 artabes (de céréales ?) : ἐνιαυτὸν `τὰς´ (ἀρτάβας) υν τὰς δοθείσας (sc. τῷ μ[οναστηρίῳ) au lieu de ἐπὶ αὐ{τὸν}`τὰς´ {τουν} τὰς δοθείσας. Il semble que ces artabes étaient aux mains d’Isakos, d’après le ἐπάνω μου du début la l. 13, car cette locution est à comprendre, « sous ma responsabilité » et non pas « à mon égard »[10] . Il semble aussi que notre Isakos (ou le monastère) ait commis, dans cette affaire, une faute ou une négligence pour laquelle il demande ensuite le secours de son correspondant (ἐμαυτῷ βοηθῆσαι, l. 16). Isakos a gardé ces artabes pendant dix mois pour les vendre, εἰς δέκα μῆνας εἰς πρᾶσιν. Il n’a pourtant pas pu le faire (καὶ οὐκ ἐδυνήθη̣[ν l. 13)[11] ou, plus probablement, il n’a pas pu, pendant ce temps, protéger ces denrées de la pourriture et d’autres dégâts puisque la l. 14 commence par ἐκ τῆς σήψεως καὶ ἐκ τῶν ποντι[. La forme ποντι[ est discutée à la n. 14, où sont proposées des résolutions en rapport avec πόντος, la mer, et l’idée de risque de mer, soit ποντικῶν ou ποντίων (« marins ») ou encore ποντιζομένων (« jetés à la mer, coulés »). Cependant, les éd. remarquent que ces mots relèvent du registre lexical poétique et que ce sont aussi des hapax papyrologiques. Comme ποντι[ est sur le même plan que σῆψις, on doit néanmoins, comme l’ont tenté les éd., chercher un mot désignant quelque dégât physique pouvant frapper des denrées dans un lieu de stockage. Je n’en vois pas de plus fréquent et ni de plus redoutable que les souris ou les rats[12]. De fait, le mot ποντικός (par prétérition de μῦς) a bien ce sens en grec médiéval [13]. On l’a encore en grec moderne avec ποντίκι et d’autres graphies. Les Égyptiens du Moyen Âge le connaissaient, à preuve le glossaire gréco-arabo-copte P.Lond.Copt. 491 qui enregistre, p. 234, les équivalences entre grec ποντικός, copte (ⲟⲩ)ⲡⲓⲛ et arabe fār). On résoudra donc ici ἐκ τῶν ποντι[κῶν, « du fait des souris ». Le papyrus de Genève en donne la première et la plus ancienne attestation documentaire.

Il s’agit de la partie inférieure droite d’une pétition datée de 551 soumise par une femme, une affranchie, [ἀ]π̣ελευθέρας (l. 5). Elle a déjà été améliorée par Berkes[14] et Hagedorn. La date post-consulaire finale, aux l. 8–10, a pu être en retrait par rapport au libelle proprement dit, ce qui impliquerait qu’aux l. 1–7, il y a plus de place à gauche pour des restitutions que les éd. ne le supposent (elles évaluent les pertes à 1 ou 2 lettres).

l. 4 : cette ligne a d’abord été lue [ὁ] δεσπ(ότης) προση̣μ(ανθεὶς) τῆς̣. Berkes a identifié des vocatifs de politesse en asyndète, à l’adresse du destinataire du libelle, suivis d’une formule de remise ] δέσποτα, πρόστα(τα) π(αρὰ) τῆς ⎜ ([ἀ]π̣ελευθέρας). En vertu de ma remarque sur les lacunes, on pourrait compléter π(αρὰ) τῆς ⎜ [αὐτῆς (nom de la personne) ἀ]π̣ελευθέρας Ἄπα Ιωάννου (sur ce nom voir Berkes), mais tout aussi bien ] ̣ ἐλευθέρας (au sens d’épouse). En faveur de cette lecture, on peut invoquer la grande rareté d’ἀπελεύθερος/-θέρα à l’époque tardive et la popularité d’ἐλευθέρα pour désigner les femmes mariées, comme je l’ai noté dans P.Sorb. II 69, p. 52. La l. 6 fait allusion à un autre Jean qui peut être un parent de la pétitionnaire.

Cet acte de conciliation hermopolitain très fragmentaire, attribué au VIe s., concerne un partage de biens. Il implique, entre autres personnes, d’après la l. i, 2, Νόννας καὶ Ολ[. Cette Νόννα revient en i, 7, où elle semble associée à une sœur, dont le nom a disparu dans la lacune finale, mais qui était une moniale d’après i, 8 : μοναζούσης θ[υ]γ̣α̣τέρ[ων. Le document appartient certainement au dossier hermopolitain de Νόννα fille d’Ὀλυμπιόδωρος (P.Lond. III 1310, p. 250 ; 1322 [SB XX 14458] ; P.Lond. V 1740), ce qui peut aider à combler les l. i, 2 et i, 8. En i, 2 on lirait Ὀλ[υμπιόδωρος. En ce cas, le père serait associé à sa fille Nonna dans le partage, mais il peut encore s’agir de la sœur de Nonna, qui aurait reçu le nom de son père, soit, pour i, 2, une restitution Ὀλ[υμπιοδώρας et dans la lacune de i, 8 Ὀλυμπιοδώρας.

Les pièces londoniennes sont datées du VIIe s., ce qui est bien probable au vu des données institutionnelles, aussi faudrait-il revoir à la baisse la datation du texte de Genève.

Ce difficile contrat du VIIe s., rédigé dans le village héracléopolitain de Leukogiou, a été réédité par J. M. Diethart et M. Hasitzka[15], qui, entre autres améliorations, l’ont identifié comme une reconnaissance de dette (l. 7, γραμμάτιον) [16]. Je crois qu’après le διὰ γὰρ τοῦτο rétabli par Diethart et Hasitzka à la fin de la l. 11, il y a lieu de lire la l. 12 πεπ̣οί[η]μαί [σοι τὴν] π̣αροῦσαν ὁμολογία(ν) au lieu de πετ ̣ ̣ ̣ [ ̣]γ ̣ ̣[ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣] ̣αρο ̣ ̣ ̣[ ̣] ̣ ̣ ̣λ ̣ ̣. D. Hagedorn, qui confirme cette lecture, me fait remarquer que ce formulaire avec διὰ γὰρ τοῦτο κτλ. se retrouve dans un autre texte tardif de Leukogiou, P.Dub. 24, 9–10[17].

Dans ce reçu de « capitation » d’époque arabe, déjà amélioré par N. Gonis[18], il faudrait, l. 2, insérer le sigle des carats (/) devant le chiffre δ.

Dans cette liste de noms tardive (ὀνόματα) l’entrée de la l. 4 se présente comme suit Γεό̣ρ̣γ̣ειος Πλά̣κ̣ο` υ ´ .[.] ̣α̣[ ̣ ̣ ̣, soit « Georgios fils de Plakos ». D’après la n. 4, le dernier nom est peu et mal attesté. En fait, le signe qui suit la combinaison du ο et du υ () est un ν ouvert. Cela conduit à restituer le nom de métier πλακουν[τ]ᾶ[ς, qui désigne une sorte de pâtissier[19]. C’est encore un πλα̣κ̣[ουντᾶς qu’il faut reconnaître à la l. 7, au lieu de Tαμειανὸς Πλα̣ ̣[. D. Hagedorn, qui a bien voulu donner son agrément à ma conjecture, me fait remarquer que la liste comporte une autre détermination technonymique avec le Γεόργειος Τέκ̣τ̣ο̣[νος de la l. 5 (lire τέκ̣τ̣ω̣[ν; voir la n. 5).

Il s’agit d’un compte tardif d’arriérés de dettes fiscales. La l. 5 fait état d’un débit (ὑπὲρ) γραμμ(ατέως) Ἰωάννου νοταρ(ίου) νο(μίσματα) ιβ, ce qui est traduit « pour le secrétaire, le notaire Iohannès ». Cela fait une syntaxe étrange, qu’on peut régulariser en lisant γραμμ(ατείου), ou γραμμ(ατείων), soit « au titre de la (ou des) reconnaissance(s) de dette du secrétaire Joannès ». Ce sens de γραμμάτειον (γραμμάτιον) est compris depuis longtemps et n’a pas été manqué dans P.Gen. IV 190, 23–24 et 26. Voir par ailleurs ci-dessus ad P.Gen. IV 189.

D’après son endossement, cette lettre tardive, mutilée à droite, est adressée à Solon, gouverneur militaire (δούξ), par le σχολαστικός Paulos [20]. Ce dernier rappelle au duc le cas de Phoibammon, un militaire d’après son prédicat de καθοσιωμένος,

l. 1 (καθωσιωμένος). Ce Phoibammon a dû commettre quelque faute, où il y va de son grade (ζώνη, cingulum, l. 3). La

l. 1 se présente ainsi Φοιβάμμων ὁ καθοσιωμ(ένος) ὑποαγανακτήσειν τῆς ὑ̣[. On ne voit pas pourquoi l’infinitif ὑποαγανακτήσειν serait au futur, alors que

l’affaire semble très actuelle. Par ailleurs, comme le remarquent les éd., la forme de ce verbe rare devrait être ὑπαγανακτήσειν. Il est plus simple de

couper ὑπὸ ἀγανάκτησειν (= ἀγανάκτησιν), sur le modèle d’un texte de Vienne publié récemment[21]. Cette

notion, de même que la « colère », ὀργή, exprime le mécontentement d’une autorité quand une loi ou une règle sont violées. En conséquence, le groupe final

τῆς ὑ̣[ est certainement à lire ὑ̣[μετέρας[22] μεγαλοπρεπείας sur le modèle de la l. 4, soit le début d’une

allusion périphrastique au duc Solon. Nous avons précisément μεγαλοπ(ρεπ ) du début de la l. 2, qu’il est tentant de résoudre μεγαλοπ(ρεπείας) et de

rattacher à ὑ̣[μετέρας, ce qui permettrait d’évaluer a minima la lacune la l. 1[23]. Quelle que

soit l’étendue des pertes textuelles, la locution ὑπὸ ἀγανάκτησειν κτλ. doit aller avec le γενόμενος du début de la l. 2. On comprendra « Phoibammon le

loyal (militaire) étant tombé sous le coup de l’indignation de votre (glorieuse ?) magnificence ».

Ce papyrus oxyrhynchite très dégradé appelle des remarques, surtout pour les l. 2–4. Les conjectures que je vais proposer s’appuient sur son image en ligne (www.psi-online.it/documents/psi;7;771). Le début de la l. 2 est conservé, si bien qu’on peut évaluer les pertes textuelles à gauche avec plus de précision que ne le marque l’éd. Comme la fin de la l. 3 est en partie conservée, il y a de la place à droite pour au moins 30 lettres aux l. 1, 2, 4 et 5. L’éditeur avait en son temps (1925) proposé dans ses notes des restitutions plausibles[24] qu’il aurait directement pu incorporer à son texte.

Il s’agit de l’enregistrement d’une vente, sans doute d’une maison, consentie par un citoyen de Bostra (l. 2). Le texte comporte plusieurs dates, jalonnant des transactions successives, mais la plus récente, qui est celle de la rédaction, est 321 (l. 1)[25].

Le début du document se présente comme suit (l. 1–5)[26] :

L. 1 : à en juger d’après l’usage oxyrhynchite de l’époque, il n’est pas nécessaire de supposer de perte après τὸ β (ainsi mois et lieu).

L. 2 : les noms sont signalés comme énigmatiques par l’éd., n. 2. En réalité, Ἐνίας, nom du vendeur, de lecture certaine, est une forme phonétique d’Αἰνίας ou Αἰνείας qui est un nom bien attesté en Arabie, notamment à Bostra[27]. En revanche le patronyme est à première vue isolé. Μalgré l’exponctuation éditoriale, le π me paraît sûr et a des parallèles dans le document. Je suggère, avec épenthèse du π, une forme du nom Εμρανος (fém. Εμρανη) dont nous avons plusieurs attestations en Trachonitide et dans le Hauran, c’est-à-dire dans les environs de Bostra [28].

Après la formule d’origo ἀπὸ Βόστρων Συρίας, l’éditeur a omis, simplement juxtaposée à Συρίας, la spécification Ἀραβίας, bien visible sur l’image. Il semble que le scribe ait compris Συρίας comme une donnée géographique[29] et qu’il ait voulu ajouter, avec Ἀραβίας, l’appartenance provinciale[30].

Notre Ἐνίας est assisté d’un garant, un συμβεβαιωτής. La fin de la l. 2 peut se restituer de manière plausible en combinant des conjectures de l’éd., n. 2 et 3, et la formulation analogue d’un acte de 324, P.Oxy. LXIII 4359, 8–9 : καὶ τῇ ἰδίᾳ [πίστει εἶναι κελεύοντος καὶ ἐντελλομένου. Au début de la l. 3, on peut suivre l’éd. avec δίχα ἐμ]πο̣δισμῶν. Le garant se déclare donc (sans obstacle juridique ou autre) fidéjusseur et mandator [31].

L. 3 : ce συμβεβαιωτής est un vétéran ayant reçu l’honesta missio. Vient ensuite la désignation de son ancienne unité qui, en l’état actuel du texte, serait une légion. Cependant, entre la formule d’honesta missio, τῶν ἐντίμως ἀπολελυμένων, et λ̣ε̣γ̣ιῶνος, il y a quelques lettres non lues. La lecture du début de λ̣ε̣γ̣ιῶνος est en fait très peu sûre. Je crois qu’on peut substituer ἀ̣π̣ὸ̣ [32] [ο]ὐ̣ιξιλλατίωνος (il y a un tréma sur le premier ι, ce qui facilite l’identification du signe). Le garant avait donc servi dans une vexillatio de cavalerie[33]. La fin de la ligne peut se lire τῶ̣[ν. Suivait le nom de l’unité, peut-être les Mauri Scutarii (τῶ̣[ν Μαύρων Σκουταρίων (voir ci-dessous).

L. 4 : l’allusion à Hermopolis est ambiguë. Il peut s’agir du lieu de garnison de la vexillatio au moment où le texte a été rédigé, ou plus probablement, car une telle donnée est attendue, du lieu de résidence actuel du vétéran Valerius Romanos, si bien que la lecture [νῦνι δὲ καταγινομένου] enregistrée dans BL II, 2 est attrayante, même si elle est un peu courte et n’est pas la seule formulation possible. Dans les deux cas, on ne peut éviter de songer à la vexillatio des Mauri qui, dans les pièces les plus anciennes de leur dossier, sont aussi qualifiés de Scutarii. Cette unité est bien connue à Hermopolis jusqu’au début du règne de Justinien. Leur plus ancienne attestation était à ce jour procurée par un texte d’avril-juin 340[34], mais il se peut, comme B. Palme y a songé, qu’elle ait d’abord été stationnée à Oxyrhynchus[35]. Valerius Romanos aurait ainsi eu, pendant son temps de service, l’occasion de s’y faire connaître. Après l’installation des Maures à Hermopolis, Valerius Romanos les aurait suivis et, une fois mis à la retraite, aurait continué à résider à Hermopolis, mais sans perdre ses relations avec Oxyrhynchus. Notre document ferait remonter l’histoire des Maures de près de 20 années.

La lacune de droite contenait sans doute des déterminations complémentaires de l’acheteuse, Dionysia alias Sophia, ainsi une patronymie et surtout une origo. Cette origo doit être Oxyrhynchus puisque, d’après la l. 5, cette cité a déjà été mentionnée (τῆς αὐτῆς), mais on ne peut décider si cette mention d’Oxyrhynchus suivait la formule longue en faveur depuis le 3e quart du IIIe s. (ἀπὸ τῆς λαμπρᾶς καὶ λαμπροτάτης Ὀξυρυγχιτῶν πόλεως)[36], ou la même formule, mais avec abréviation des prédicats, ou à la rigueur une formule courte, sans les prédicats.

L. 5 : devant l’infinitif initial, qui se lit en fait π]ε̣π̣ρ̣α̣κέναι, on peut restituer, en s’inspirant de BL II, 2, ce qui comble au mieux la lacune, [χαίρειν. Ὁμολογῶ].

Nous lirons donc ces lignes :

Jean GASCOU

This fragmentary loan of wheat contains some remarkable features. The creditor is Apollonios, ἀπὸ δικαιοδοτῶν, “the latest dated attestation to the office of juridicus”[37]. The text is dated Tybi 10 in the consulate of Valens Aug. VI and Valentinianus Aug. III (= 5 January 378), that is, within five days from when the two emperors assumed the consulship. In a period when late dissemination of consuls was the norm, this is hardly what we would expect. In the 370s, there is another very early date by the eponymous consuls of the year, P.Vind.Sijp. 13 (Tybi 8), which however has been shown to be an inadvertence for the postconsulate; see CSBE2, p. 189 (s. a. 373). There are also other problematic consular dates from the month of January (see CSBE2, p. 90). In sum, we should consider the possibility that in the Berlin document ὑπατείας is an error for μετὰ τὴν ὑπατείαν, in which case the text would date from 6 January 379.

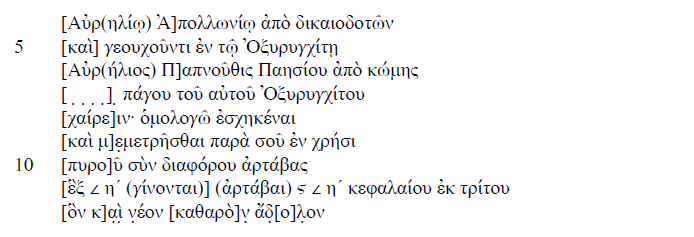

Besides the date, there are some small textual problems that call for discussion. I reproduce ll. 4–12 as they appear in the edition:

“From the left is missing a narrow strip”, the editor wrote, but he underestimated the width of this lost strip by 4–5 letters, as comparison of ll. 4ff.

with the securely restored l. 1 shows;

I have also been able to consult an image, kindly supplied by Marius Gerhard. Thus in l. 4, for Αὐρ(ηλίῳ) restore Φλαουίῳ, to match the status of an ex- iuridicus; in l. 6, supply Αὐρήλιος, without an abbreviation. In l. 9, the papyrus may well have had [καὶ παραμ]ε̣μετρῆσθαι; cf. P.Col. X 287.26

(326). But not all supplements are straightforward. [καί] is unparalleled at this point in l. 5, and there is a trace on the edge of the break; could it be

that the lacuna took away the name of the creditor’s father? In l. 7, the name of the village does not need to be as short as was thought (7 n.); the

letter after the break is γ, and the names of various villages of the 3rd pagus could fit in the break; see A. Benaissa, RSON 2.0, p. 463. In l. 10, the break would have taken away more than [πυρο]ῦ, but it is unclear what; even ἐξ οἴκου σου (cf. P.Col. 287.7) would be

too long. We would also expect σίτου rather than πυροῦ in a text of this date, though there are exceptions; see W. Clarysse, BASP 51 (2014) 105 with n. 17.

There are awkward parts in in ll. 11–12 as restored, but the image allows for a smoother text to be obtained. In l. 11, for 𐅵 η´ we should read the symbol

for 2/3, which further suggests a different supplement for the lost part of the line. We may also restore a common formula in

l. 12; cf. P.Mert. I 36.11 (Oxy.; 360) σίτου καθαροῦ ἀρτάβας δύο ἥμ̣ισ̣υ | ὅνπερ πυρὸν νέον καθαρὸν ἄδ̣ολον κτλ. In sum, I propose that the text be

reconstructed as follows:

The papyrus comes from the first excavation season of Grenfell and Hunt at Bahnasa (see P.Cair.Cat., p. 17), and is among the few not published in P.Oxy. It contains a ‘List of payments connected to an estate (?)’ (but the question mark is unnecessary), assigned to the sixth century. The payments were thought to be either of 3 or of 6 solidi, but the sums involved are only the one-tenth of them: γ and ϛ are always followed by two small oblique strokes high in the line, and these signal fractions, viz. 1/3 and 1/6.

One of the tax-payers in this fourth-century account of the vestis militaris was read as κλ(ηρονόμοι) Ἀλυπίος (iv.6). Ἀλυπίος for Ἀλυπίου is strange in a text where every other case is written correctly, but a closer look at the published photograph reveals that the scribe did not err: instead of κλ(ηρονόμοι), I suggest reading φλ/ = Φλ(άουϊος). The scribe used the same abbreviation in ii.3, Φλ(άουϊος) Φιλόξεινος, and probably also in iv.18, where in place of Φ̣λ̣ά̣ο̣[υιος read φλ/ ̣ ̣ [. This Fl. Alypios is not known otherwise (it is not likely that he is to be identified with Fl. Areïanos Alypios, praeses of Augustamnica in 351–352).

This ‘fragment concerning reimbursement’, dating from 350 or 351, refers to ]ω̣ι̣ Πλουτάρχου βουλευτ̣[ῇ (l. 4). The broken letter on the edge is surely the right-hand part of nu, i.e., read ]ν̣ι; it is tempting to restore Σαραπίω]ν̣ι. The only councillor said to be the son of Ploutarchos in fourth-century Oxyrhynchus is Sarapion son of Ploutarchos, attested between 361 (P.Oxy. LXVII 4606) and 373 (P.Mich. XX 814); for references, see P.Mich. XX, pp. 25f. If the identification holds, it will add a whole decade to his known career.

Two further new readings may be recorded here. In l. 6, πα]ρασχεθῆσά σοι εἰς λ̣[όγον, read παρασχεθέντ̣α; cf. 5 τὰ μεταβληθέν[τα. In l. 9, for ο̣ὗπερ read ἅσπερ.

According to SPP III2.5, p. xxxi n. 37, lines 4–5 of this granary receipt of 44 ought to read μ̣[έ(τρῳ) ξυσ]τ̣ῷ καν|κέλλῳ (μ̣[έτρῳ] τ̣ῷ ed. pr.). Similar documents of this date indicate that μέ(τρῳ) ought to be described as δημοσίῳ; cf. P.Oxy. XLIV 3163.9 (71) or XXXVIII 2841.8 (85). A photograph indicates that before the break there is a low trace that could suit many letters, and that there is enough room in the lacuna to restore δ̣[η(μοσίῳ) μέ(τρῳ) ξυσ]τ̣ῷ.

This is a letter addressed to Georgios, a senior functionary of the estate of Apion III, who is the usual addressee in the ‘Victor–George’ correspondence; the time is the second decade of the seventh century. It starts with a reference to a request made concerning the people of three villages: ἕνεκεν τῶν ἀπὸ̣ Ἀκ[τουα]ρ̣<ίου> κ̣α̣ὶ̣ Ἡ̣ρ̣α̣κλοασιανοῦ καὶ Κευώθεως (l. 2). The reading does not inspire confidence; there is also no apparent reason for the scribe to abbreviate. Furthermore, if Aktouariou were located, as is likely, near Oxyrhynchus, this ‘would throw further doubts on the restoration of P.Oxy. 1856.2, since that village is mentioned alongside Herakloasianou and Keuothis, the latter situated in the Cynopolite nome’ (Benaissa, RSON 2.0, p. 26). Following inspection of the on-line image, I propose to read Ἀκ[ούτ]ου̣. This settlement was probably close to another securely attested in the Eastern Toparchy and the 5th pagus (see RSON2.0, p. 25), and hence not too far from the Cynopolite border (see the map in J. Rowlandson, Landowners and Tenants in Oxyrhynchus, Oxford 1996, p. xiv).

The association of Akoutou with the Apion estate was not known previously. It was closely associated with Sarapionos Chairemonos in 562/563 (P.Oxy. VIII 1137), and the latter village was the centre of a prostasia administered by the episcopal church of Oxyrhynchus in 573 (P.Oxy. XVI 1894), after which our record on Sarapionos Chairemonos remains silent.

Called a ‘petition’ by the editors, this “is certainly … a letter of the usual Byzantine type” (H. I. Bell, CR 57.2 (1943) 83; not in BL), assigned to the sixth-century. The back contains delivery instructions: ἀ̣[π]ό̣δ̣[ος τῷ] κ̣υ̣ρ̣ί̣ῳ̣ Σα̣ραπί̣ω̣[νι] κεφφ πό̣λ̣ε̣ω̣ς̣ Κ[. There are two peculiar features: first, κεφφ, with the last letter duplicated, indicates a plural form, and the main text refers to a plurality of persons (ll. 2, 7, 9), but the addressee appears to be one (Sarapion); second, the description of one or more kephalaiotai as ‘of a city’ is unique. An image (http:// arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/1g05ff19f) shows that the reading of the first part of the address cannot be verified; ἀ̣[π]ό̣δ̣[ος τῷ] is probably imaginary, κ̣υ̣ρ̣ί̣ῳ̣ is not there (only ω is secure), and Σα̣ραπί̣ω̣[νι] is impossible: the word begins ϲτρα, and τ̣ι̣ω̣ may have followed, but I am uncomfortable with ϲτρατ̣ι̣ώ̣(τῃ). What is certain, however, is that πό̣λ̣ε̣ω̣ς̣ is a misreading; read κεφ(αλαιωταῖς) Πακερκ[η (κεφ⸉φ⸉ pap.). The reference to ‘those of your village’, τῶν ἀπὸ τῆς ὑμετέρας κώμης, in l. 7 now becomes concrete; Pakerke is a well-known Oxyrhynchite toponym (see Benaissa, RSON2.0, pp. 241–245). There is a curious second person singular pronoun in l. 6, ἡμεῖς ἐσμέ⟨ν⟩ σοι ὀφείλοντες ζητῆσαι, but I suspect we have to read ἐσμὲς οἱ ὀφείλοντες; ἐσμές for ἐσμέν would be curious, though the interchange ν > σ in final position is attested (see Gignac, Grammar i 132).

The letter itself appears to end, θως αυτ( ) δεσπ( ) (l. 10), which is peculiar; read ἕως ἄρτ(ι) δεσπο(τ ). It is tempting to resolve δέσπο(τα), but that would sit oddly with the plurality of addressees; on the other hand, the vocative plural of δεσπότης is not attested in papyri.

This is a list of toponyms connected with the Apion estate, assigned to the sixth century. A digital image (http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/000002601) allows for some small textual improvements to be made:

In l. 6, the editors read Τρίγου, stating that ‘Τριγήου … cannot be read here’: the papyrus clearly has Τριγύου. Τρίγου may have been influenced from the purported occurrence of this form in P.Iand. III 51.21, but there too one should read Τριγύ̣ου: upsilon is represented by a slight wave at the end of the crossbar of gamma.

In l. 8, instead of Καλουρίας it is possible to read Καλωρίας, which is the name of this locality almost everywhere else.

In l. 9, ed. has μηχ(αν)ῆ[ς] Φαησερῶ, ‘possibly read Φανσερῶ’. BL VI 120 records the suggestion, ‘Viell. μηχ(αν)ῆ[ς] Φανέρω (vgl. P. Oxy. 2244 III 40), I.F. Fikhman’. The papyrus has μηχ(ανῆς) Φανσερω.

In l. 11, ed. has Νεπ( ), ‘possibly read Νέου’. Νέου is in fact the only viable reading.

In a strong-worded message, a riparius threatens the village authorities that if they do not deliver those responsible for damages in the fields and the field-guards who neglected their duties, he would arrange so that a tribunus set upon their houses, καὶ ὅσ̣α̣ | ἔχεται ἐν ταῖς οἰκείαις ὑμῶν ποιῶ ἀπαλλαχθῆναι τοῖς στρατιώταις (ll. 6–7). The on-line image shows that in place of ἀπαλλαχθῆναι the papyrus has ἀναλωθῆναι: the soldiers would ‘consume’ whatever the recipients of the message have in their houses.

The text has been assigned to the sixth century but a date in the second hand of the fifth seems more likely.

One of the persons mentioned in this contract of 566–568 is said to be υἱὸς Σ̣ίωνος. As the on-line image indicates, epsilon seems the more natural reading than the dotted sigma, and Ι propose to read Εἴωνος (l. Ἴωνος).

The guarantor in this deed of surety of 609 undertakes that the person for whose good behaviour he pledges should not be absent nor transfer to another place: κα[ὶ μηδαμῶ]ς αὐτὸν | ἀπολειμπά[ν]εσθαι [τὸ αὐτὸ ? μή]τε μεθε̣ί̣στασ(θαι) | εἰς ἕτερον̣ <τό>πον̣ (ll. 23–25). The editor’s hesitation over the supplements in l. 24 reflects the uncertainties in the early decades of papyrology, but another text edited in the same volume, PSI I 52.22, contains the formula that will recur in several other documents published later and is what we should restore here: the on-line image allows reading [μήτε μ]ὴ̣ν μεθε̣ί̣στασ(θαι).

The countersignature in this order to supply wine was first read as Ῥίπυγξ <?> ἐ̣π̣(ιτηρητὴς ?) σεσημείωμαι. The first part has been shown (BL VIII 393) to be the Oxyrhynchite era year ριη πζ (118/87 = 441/2), but the dubious ἐ̣π̣(ιτηρητὴς ?) has remained unchallenged. In Oxyrhynchite texts of this kind and date, the name and function of the person who countersigns the order is only sporadically stated, so that there is no need to expect anything to be written before σεσημείωμαι. There is writing at this point (see the on-line image; I have also seen the original), but it cannot be matched with any letter, and its purpose is obscure. It should also be noted that the countersignature is in a different hand from that responsible for the main text.

This is a fragmentary deed of surety of the late sixth or early seventh century. The person under surety originates from a locality whose name ends in ]ηβης. Fikhman, BL VII 232, suggested [μεγάλης Καλ]ήβης or only Καλ]ήβης (l. Καλύβης), and this is certainly right: lambda is extant in the papyrus. Read Κα]λήβης; we cannot tell whether it was preceded by Μεγάλης.

The reading and reconstruction of the endorsement of this text in ed. pr. are problematic:

ἐγγύη ought to stand at the beginning of the docket, not in the second line. After that, there would be the name of the guarantor in the genitive and his origo (that latter is given in l. 1), possibly preceded by γενομένη or γεναμένη. This would have been followed by ἀναδεχομένου and the name and patronymic of the person under surety; in l. 2, I read ]ειον Ὀ̣ννωφρίου. His origo would have come next, but I have not been able to read anything convincingly in the traces. For the construction overall, cf. e.g. PSI I 61 or 62.

The text is an account of transport of wine produced in various Oxyrhynchite localities in 345/346. The transport is made by ships; for a typical entry, cf. e.g. l. 10, μετηνέ]χθ(η?) διὰ πλοίου Ἱέρακος ναύτου γεο[υ]χ(ικοῦ). In l. 16, the editors printed διὰ πακ( ), and hesitantly proposed to read διὰ πάκ(τωνος) in the note; but the context makes πάκ(τωνος) inescapable. Cf. P.Oxy. L 3598.1f. (iv) λόγ(ος) σίτου ἀνενεχθέντος διὰ̣ | πάκτωνος. We may also consider whether ἀνηνέ]χθ(η) is preferable to the tentative μετηνέ]χθ(η) in ll. 3 (μετ]ηνέχ[θ](η)), 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 18.

The wine was produced in various Oxyrhynchite localities (see BL VII 238); one other known toponym occurs in l. 20, ἀπὸ] κτημ(ατ ) των π( ) ̣[ ̣ ] ̣λω, for which the editors note: “Forse ἀπὸ ]κτημ(άτων) τῶν π(ερὶ) []λω <nome del villaggio>”. Π̣[λ]ε̣λω suits the traces and the space; on this village of the Middle toparchy, and in the 6th pagus at that time, see Benaissa, RSON2.0, p. 287.

Two further textual amendments may be recorded here. In l. 17, for the singular ἐπί̣π̣αν̣ read ἐπὶ τὸ α(ὐτό) (α ̄ pap.) In l. 18, ἀ[πό may be read instead of ̣ ̣ ̣[.

There have been several small advancements in the interpretation of PSI X 1122 since it first appeared in print, most important of which was the establishment of its Oxyrhynchite origin, but several problems have remained. In this document, David son of Paulos (l. 31, ἐγὼ Δαυὶδ υἱὸς Παύλου; in the untranscribed l. 2, read Παύ]λου μη̣τ̣ρός), who originates from an unknown epoikion, addresses a certain Victor (in l. 4, for σοι κτήτορι read σοὶ Βί̣κτορι) from Oxyrhynchus (at the start of l. 6, read [τῆς Ὀ]ξ̣[υ]ρ̣[(υγ)χ(ιτῶν) πόλε(ως)), and acknowledges that he has received two solidi at 23 carats each: νομίσμα[τα] δύ[ο ̣ ̣ ] ἀπὸ κερατί(ων) | εἰ[κο]σιτρι[ῶν]· (γίνονται) χρ(υσοῦ) νο(μίσματα) ἀπὸ κερ(ατίων) κγ (ll. 9–10). David agrees to supply 200 sekomata of wine for 2 solidi (ll. 11–13, ὑπὲρ δύο (with BL VIII 406) | νομισμάτ̣[ων] ̣ ̣ ̣ οἴνου πενταξ(εστιαῖα) | σηκώματ̣α̣ διακ[όσια]), and keep the remaining 11 1/2 carats (ll. 19–20 τὰ ἄλλα ἕνδεκα ἥμισυ | κερ(άτια)) as an advance payment for his oxen.

According to the text of ed. pr., the sum borrowed was 2 solidi, so that there are 11 1/2 carats, i.e. 1/2 solidus, unaccounted for. The problem

was recognized in the edition: “se [τὰ ἄλλα] non è errore di redazione invece di ἄλλα, la spiegazione bisognerebbe cercarla nel rr. 11 sqq. e supporre che

ivi ad ὑπὲρ τῶν β (δύο BL VIII 406) νομισμάτ̣[ων] seguisse ‘meno 11 1/2 keratia’” (19 n.). This, however, is impossible: the solidi are of the 23-carat

variety, which excludes the alleged deduction. The solution should be sought in ll. 9–10, where the text is suspicious: there is a break after δύ[ο in l.

9, and there is no reference to the number of solidi in l. 10. The on-line image allows reading δύο̣ ἥ̣μ̣[ισ]υ̣ in l. 9, and ν[ο(μίσματα)] β [ ἀ]πό in l.

10, but I cannot tell what came before in οἴνου l. 12. (The middle parts of ll. 8–11 are in a fragment now joined to the piece on the right, but the

fragments are not contiguous.) David received

2 1/2 solidi.

After BL VIII 406, the endorsement reads ] ̣ ει( ) οἴ(νου) (πεντα)ξ(εστιαῖα) σηκ(ώματα) σ (καὶ) (ὑπὲρ) προχρεί(ας) βοϊδί(ων) χρ(υσ)ο(ῦ) κερ(άτια) ια . The part lost to the left will have contained a reference to the 2 solidi paid for the wine, followed by a word connecting them with it. The nearest parallel comes from the endorsement of P.Oxy. LXI 4132 (619): γρα(μμάτιον) Ἰερημίου υἱ(οῦ) Ἰωσὴφ ἀ̣π̣ὸ Παγ̣[γου]λ̣ε̣ε̣ί̣ο̣υ̣ με̣τ̣’ ἐγγ(υητοῦ) Στεφάν̣ο̣υ̣ προ(νοητοῦ) χρ(υσοῦ) ν̣ο̣(μισματίων) η̣ | ἰδ̣(ιωτικῷ) ζ̣υ̣γ̣(ῷ) τ̣ι̣(μῆς) οἴ(νου) (πεντα)ξ(εστιαίων) [σ]η̣κ(ωμάτων) ω. The trace after the break is a horizontal, but it is hardly part of tau, so that τ̣ει(μῆς) is not an option (τιμή is not mentioned in the main text, but there is a damaged part in l. 12 that precludes certainty on whether it was written). Furthermore, τ̣ι̣(μῆς) in P.Oxy. 4132 is dubious, and in fact epsilon should be read instead of tau (see the on-line image). Thus both texts offer the same reading, ει( ), which may be expanded as εἰ(ς); for the concept cf. P.Oxy. LVIII 3960.36f. (621) ἀπὸ νο(μισμάτων) ιβ ἰδ(ιωτικῷ ζυγῷ) | εἰς οἴνου κνίδ(ια) χ. Thus the text on the back of PSI 1122 would have run, [γρα(μμάτιον) Δαυὶδ υἱοῦ Παύλου ἀπὸ ἐποικίου name χρ(υσοῦ) νο(μισμάτων) β εἰ(ς) (κεράτια) κ]γ̣ εἰ(ς) οἴ(νου) (πεντα)ξ(εστιαῖα) σηκ(ώματα) σ (καὶ) (ὑπὲρ) προχρεί(ας) βοϊδί(ων) χρ(υσοῦ) κερ(ατίων) ια (there are scattered traces from the first part of the docket, but it is not easy to match them with letters, at least on the basis of the image).

PSI 1122 is closely related to P.Michael. 35, another loan of money with repayment in kind (or a sale with deferred delivery), this time of wheat; both are dated to a tenth indiction, and are signed by the same notary. Its endorsement was read as, Δαυὶδ μείζ(ων) υἱ(ὸς) Παμου[θίου - - - ]μ̣μαιουτ( ) τοῦ Ὀξυρ(υγ)χί(του) νομοῦ χρυ(σοῦ) νο(μισμάτιον) εἰ(ς) (κεράτια) κβ 𐅵 σίτου ἀρτ(άβαι) κ[. I examined the original at the British Library, and read a slightly different text: [γρα(μμάτιον)] Δαυὶδ μείζ(ονος) υἱ(οῦ) Παμου[θίου ἀπὸ ἐποικίου] Ἀμβιοῦτ(ος) τοῦ Ὀξυρ(υγ)χί(του) νομοῦ χρυ(σοῦ) νο(μίσματος) α εἰ(ς) (κεράτια) κβ εἰ(ς) σίτου ἀρτ(άβας) κ. The hand is the same as that in PSI 1122.

The origin of the debtor (or seller) in P.Michael. 35 should be restored in the prescript of the document, where in frA.7 read ἀ]πὸ ἐ̣π̣ο̣ι̣κ[(ίου)] Ἀ̣[μβιοῦτ(ος) in place of ἀ]π̣ὸ [ ̣] ̣ ̣κ[ ̣] ̣ [. It is only a coincidence that he is called David, like his counterpart in PSI 1122, but it may not be accidental that the creditor (or buyer) is also called Victor, here described as a κολλεκτάριος and ζυγοστάτης. It may well be that the two documents come from Victor’s ‘papers’.

One other textual point requires attention: ed. pr. has καὶ | ἐπὶ τούτοις πᾶσιν ἐπω̣μ(νύμενος) in frB.13f., but indicates that the papyrus has επω̣μο. This led to the suggestion to read ἐπ(ερωτηθεὶς) ὡμο(λόγησα) (BL V 68), but this should be abandoned. Read ἐπω̣μοσάμην, which goes with the prepositional phrase that precedes it; for this formula, cf. SB V 8029.23 (537), P.Oxy. I 138.33 (610/611), etc. PSI 1122.28 also has ἐπω̣μοσάμην, but in a different construction.

I close with a note on the date of the two texts. In ZPE 153 (2005) 171, I wrote that they were likely to date from the early Islamic period on the basis of the references to solidi of 23 and 22 1/2 carats. Solidi of 23 carats occur already in 639 (SB XXII 15729), but I am not aware of any post-Conquest text that attests a solidus of 22 1/2 carats. Thus the tenth indiction mentioned in PSI 1122 may correspond to 651/652, and P.Michael. 35 may date from 2 April 652 (but they could also date from an indiction cycle later). If this holds, these would be two of the latest dated documents attesting financial activities in the city of Oxyrhynchus after the Islamic conquest.

The endorsement of this loan of money of 565 was read as π(αρὰ) Παπνουθί(ου) υἱοῦ Κοσμᾶ ἀπὸ τῆς Ὀξυρυγχιτῶν πόλεως. π(αρά) is out of place; the on-line image shows that the papyrus has γρ(αμμάτιον), like many other loans. The reference to the name of the document is given in the main text, including the subscription, where read [στοιχε]ῖ̣ [μο]ι̣ τ̣ο̣ῦ̣το τὸ γ̣ρ̣α̣μ[μ]ά̣τ̣ιον (l. 26; ed. pr. only indicates a lacuna before τ̣ο̣ῦ̣το); for the phrase, cf. PSI I 63.34f., X 1122.31f., etc.

There is something that has not been deciphered at the end of l. 21: ̣αν ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣τως. There is an upright before alpha that I cannot explain, but then I read ἀνυπε̣ρ̣θ̣έτως (there is apparently a diaeresis over upsilon); for the form of υπ, cf. ὑποκ(ειμένων) in l. 23. The introduction of this adverb after the listing of the items pledged for the loan is awkward, but it is part of a formula that continues κινδύνῳ τῶν ἐμοὶ ὑπαρχόντων, as here.

This is a fragmentary grain receipt assigned to the fifth century. As the editor points out, the reference to a particular measure in l. 4 points to the area of Oxyrhynchus or Hermopolis as its origin: μέτρῳ παραλυμτικῷ, l. παραλημπτικῷ (παραλητικῷ ed. pr.; for the omission of pi, cf. P.Stras. VI 557.21f. (291) παραλημτι|κῷ). It may well be that it is Oxyrhynchus. At the start of the extant text, we find αὐτῆς οἰκίας̣ δ̣[ιὰ - - - ]|πουνίου ἐξ̣ Ὀ̣ξυρ̣[ύ]ν[χ(ων)] π[όλ(εως)] (ll. 2–3); the editor notes that πουνίου must be part of a name: [Καλ]πουνίου or [Καρ]πουνίου. This recalls a passage in one of the most often cited documents from fifth-century Oxyrhynchus, P.Mil. II 64.4 (440): the person who has been thought to be the first colonus adscripticius to occur in a papyrus is said to originate ἀπὸ ἐποικίο[υ] Κ[α]λπουνίου τοῦ αὐτοῦ νομοῦ τῆς αὐτῆς θειοτάτης οἰκίας. It is worth considering whether the reference is to the same locality and the domus divina. However, the reading ἐξ̣ Ὀ̣ξυρ̣[ύ]ν[χ(ων)] π[όλ(εως)] cannot be verified; all that can be read with certainty is the second xi, and the phrase itself is rather unexpected.

One of the entries in this account reads οἴνου χο(ῦς) α (l. 8). χο(ῦς) is represented by χ and a superscript letter that should be read as delta, not omicron (see Tav. XLVI). This is the standard abbreviation for (τετρά)χ(οον), a typical Oxyrhynchite container, on which see N. Kruit, K.A. Worp, APF 45 (1999) 106.

The account is written on the back of a document that may date from 255–260 (PSI XVI 1646). The 28 drachmas thought to be the price of one chous of wine suggested a date around 270. There is no need to alter this on the basis of the new reading; see the references collected in PSI XVI 1642.8 n.

This sale of 324, a re-edition of PSI IV 300, is addressed to a person described as ] ̣ῳ ἴλης τρίτης Ἀ[στο]υρίων (l. 2). According to the second editor, “The letter before omega after the break at the start of the line seems … to be … probably either kappa or chi. This should represent a rank in the unit, which I have not been able to identify; but it is possible that the rank was omitted and this is the end of a second name.” (BASP 27 [1990] 88). The latter option is less likely; the reference must surely be to a rank, and I suggest restoring βιάρ]χ̣ῳ. For other biarchs of cavalry units in contemporary documents, see M.Chr. 271.5f. (359) βίαρχος οὐεξελλ[ατίωνος] | ἱππέων καταφρακταρίων, and, though the word is restored, P.Oxy. LX 4084.6 (339) [βιάρ]χου ἀριθμοῦ ἱππέων Μαύρων σκουταρίων κ̣ο̣μ̣ιτα̣τησί̣ω̣[ν].

This receipt for chaff, assigned to the fifth century, is headed ε ̣[ ̣ ̣ ̣ ] ̣εμο Θεοδώρῳ ὀνηλάτῃ κυρί|ω μου λαμπροτάτου Φ[ο]ι̣β̣άμμων, translated as ‘- - - to Theodoros, donkey-driver of my lord, a vir clarissimus, Phoibammon’. According to the editor, the text shows “two extraordinary features”, one of them being the fact that “the letters at the beginning of line 1 are unexpected. I cannot decipher a further qualification of the donkey-driver Theodoros … Neither can I read a proper name (of the person who gave the order …)” (AnPap 5 [1993] 122, 123). There is nothing extraordinary, however; the problems largely stem from the scribe’s faulty grammar.

As we can see from the on-line image, the letter after the first epsilon is ν; combined with the Oxyrhynchite origin and date of the text, it suggests reading ἐν[τάγι]ο̣ν̣ ἐμο[ῦ] (the lost υ, if indeed written, would have been superscript, as elsewhere in the text). This expression is normally followed by the name and occupation of the person who issues the receipt; Θεοδώρω and ὀνηλάτη are not real datives but genitives in phonetic spelling, just like κυρίω. Further, Φ[ο]ι̣β̣άμμων should be taken with what precedes it (the editor considered this only as an alternative); for similar idiosyncratic uses of the nominative instead of the genitive, cf. P.Oxy. LVI 3868.5f. κυρίου Φοιβάμμων, or SB XXII 15268.1 ἐντάγιων ἐμοῦ Φοιβάμμων π̣ρ̣(εσβυτέρου). In normalized grammar, the text would run ἐντάγιον ἐμοῦ Θεοδώρου ὀνηλάτου τοῦ κυρίου μου <τοῦ> λαμπροτάτου Φοιβάμμωνος. Since the document belongs to the fifth century, this clarissimus Phoibammon may have been the son of Ioannes and brother of Samuel at a time not far removed from 489; see P.Oxy. LXVIII 4697.3–4 n.

In l. 4, ὑ̣π̣ὲ̣ρ̣ τῆς δ ἰνδ[ι]κ̣(τίωνος), the preposition should be read as ἐπ̣ί̣.

Only the top of this receipt for rent has survived. It was said to be of unknown provenance and was assigned to the fifth/sixth century, but these statements are in need of revision: the reference to the ἰδιωτικὸς ζυγός (4f., ἰδ[ιωτ]ι̣[κῷ ζυγῷ; ἰδ[ιωτικῷ ζυγῷ; ed. pr.) points to the area of Oxyrhynchus, and the hand suggests a date in the later sixth century. For this type of document, cf. PSI I 81 (595).

Nikolaos GONIS

Schon bald nach dem Erscheinen von BGU I hat U. Wilcken erkannt[38], daß in Z. 10–11 dieses Sitologenberichts (Karanis; 186 n. Chr.), wo unverständliches πυροῦ μὲν δημ(οσίου) | [ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣]πρ ἀρτ(άβας) gedruckt worden war, die Bezeichnung des Maßes stecken muß, mit dem das Getreide gemessen wurde; er schlug folgende Korrektur vor: πυροῦ μέτ(ρῳ) δημ(οσίῳ) | [ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣] πραιτ(ωρ-). Doch was sollte in diesem Kontext die Erwähnung eines Prätors zu tun haben? Die jetzt im Internet vorhandene Abbildung[39] ermöglicht die Lösung: Zu lesen ist μέτ(ρῳ) δημ(οσίῳ) | [ξυσ]τ̣(ῷ) ἔπαιτ(ον). Nach der Lücke sieht man in Z. 11 noch den langen Ausläufer eines hochgesetzen τ; das ε danach (bisher als π gedeutet) hat dieselbe Form wie auch in ἔτους genau darüber in Z. 10, und mit dem folgenden π vergleiche man den Anfang von πυροῦ in Z. 10. Die Korrektur ist gewissermaßen trivial, weil das μέτρον δημόσιον ξυστὸν ἔπαιτον weit über fünfzigmal in den Papyri bezeugt ist[40].

Eine weitere Korrektur zu Z. 28: Die dort vorgenommene Ergänzung [τεσσαρ]ακαιεικοστόν für den Bruch 1/24 ist falsch. Es muß [τετρ]ακαιεικοστόν heißen, wofür die DDbDP zahllose Belege bietet[41], während τεσσαρακαιεικοστός ansonsten unbezeugt ist.

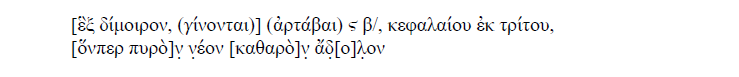

Quittung über den Erhalt der Verkehrssteuer für die elterliche Schenkung eines halben Anteils an zwei Sklaven (Philadelphia; 166/7 n. Chr.) [42]. Die anhand der Abbildung im Internet[43] von mir festgestellten Transkriptionsfehler in Z. 2/3, 5 und 9 nehme ich zum Anlaß zu einer vollständigen Neuedition, weil ich auch eine ältere Korrektur in Z. 9 integrieren und zusätzlich kleinere Änderungen bei der Setzung von Klammern und Unterpunkten vorschlagen möchte [44].

1–3 Die Zeilenfüller am Zeilenende sind in der Erstedition nicht verzeichnet worden.

1 Ein Χάρης Σαβείνου begegnet auch in P.Yale III 137, 210 (Philadelphia; 216/7 n. Chr); dieser dürfte, wie der Herausgeber Paul Schubert im Kommentar vermerkt, nicht der hier genannte Nomographos, sondern eher dessen Enkel sein.

2–3 Γαίῳ | Ἰουλ̣ίῳ: γεω[ργῷ] | ἰδίῳ ed. pr. Der Nomographos hat die Quittung also nicht „seinem eigenen Pächter“ ausgestellt, sondern einem Mann mit den römischen tria nomina, zu dem er offenbar keine näheren Beziehungen hatte. Damit entfällt ein Problem, mit dem sich Jean A. Straus in dem genannten Aufsatz ausführlich beschäftigt hat. Wie überall im Fayum, so hatten sich ganz besonders auch in Philadelphia viele ehemalige Soldaten niedergelassen; vgl. nur John F. Oates, Philadelphia in the Fayum during the Roman Empire, Atti dell’XI Congresso Internazionale di Papirologia, Milano 1966, S. 451–474 mit einer Liste dort ansässiger römischer Bürger auf S. 459–474. Bemerkenswert ist indes, daß schon die Mutter unseres Mannes sich „römisch“ nannte; s. Z. 5. Gaius Iulius Marinus könnte also schon von einem solchen Siedler abstammen; ob er wirklich das römische Bürgerrecht besaß, muß dahingestellt bleiben.

4 ὧ[ν]: lies οὗ (zu verbinden mit μέρους in Z. 7).

5 Ἰουλία Ι̣ ̣ ̣ ̣ ̣: ̣ ̣ ο̣ναιν[α] ed. pr. Den zweiten Namen der Mutter kann ich nicht entziffern. Der Buchstabe nach dem (auch sehr fraglichen) Iota könnte eventuell ein Epsilon oder (weniger wahrscheinlich) ein Sigma sein.

9 διαγράψω καὶ ἐνεγκῶ: διεγράψω καὶ ἐν̣έ̣γκω̣ (l. ἠνέγκω) ed. pr., also aufgefaßt als 2. Person Sg. Aor. des Mediums. Daß ἐνεγκῶ, also die späte Form des Futurs, zu verstehen ist, hat schon Straus, La quittance (s. o. Anm. 42) 116 korrigiert (= BL XII 20); seltsamerweise hat er aber an dem Aorist διεγράψω festgehalten (und somit einen Personenwechsel postuliert), obwohl alle Parallelen, die er zitiert, ebenfalls das Futur haben. An unserer Stelle ist an der Abbildung das erste Alpha von διαγράψω über jeden Zweifel erhaben; es kommt hinzu, daß ein Medium von διαγράφω — wenn ich recht sehe — in den Papyri sonst nirgendwo bezeugt ist.

10 Ἀν̣τωνίνου: Ἀτωνίνου ed. pr., aber man braucht den unerwarteten Fehler nicht anzunehmen, denn zwischen Alpha und Tau sind noch Tintenreste vorhanden.

12 Von Π̣[αρθικῶν] gibt es nach dem Pi noch weitere Tintenspuren, die sich aber einzelnen Buchstaben nicht zuordnen lassen.

Als „Dekaprotenquittungen“ haben die Herausgeber diesen Text von Juli–Oktober 259 n. Chr. bezeichnet, weil sie — mit Recht — der Meinung waren, daß es sich bei den hierin tätigen Einnehmern von Weizensteuern, obwohl ihr Titel ungenannt geblieben sei, wegen der Abfassungszeit und des Formulars um Dekaproten gehandelt haben müsse. Exakt an der Stelle, wo der Titel zu erwarten wäre, nämlich nach der ausführlichen Namensnennung der beiden Beamten am Ende von Z. 3, haben die Herausgeber sechs Buchstaben unentziffert gelassen und zu Ζ. 3–4 folgenden Kommentar gegeben: „Man könnte lesen ἐ̣γ̣κ̣α̣τ̣α̣|μεμετρήμεθα oder εἰσμεμε|{μεμε}τρήμεθα. Das letztere wahrscheinlich richtig.“ Allerdings beginnen andere Dekaprotenquittungen nicht mit einem Compositum von μετρέομαι, sondern dem Simplex; vgl. nur BGU II 579 = Chrest.Wilck. 279. An der jetzt im Internet verfügbaren Abbildung (http://smb.museum/berlpap/index.php/03010/), sehe ich meines Erachtens zweifelsfrei, zumal wenn ich das Wort δεκαεπτά am Anfang von Z. 13 vergleiche, daß die korrekte Lesung in Z. 3/4 das zu erwartende δεκάπρ̣ω̣(τοι). | μεμετρήμεθα ist:

Eine weitere Beobachtung: Mir scheint, daß in Z. 1 (fehlerhaft) Γαλλιηνῶν anstelle von Γαλλιηνοῦ steht; derselbe Fehler begegnet, hervorgerufen durch das vorausgegangene korrekte Οὐαλεριανῶν, laut DDbDP auch in O.Bodl. II 1637, 3; O.Wilck, 1595, 2 und SB I 776, 6, sowie ferner in der Inschrift SB IV 7290, 6; vgl. hierzu auch John R. Rea, Valerian Caesar in the Papyri, Atti del XVII congresso internazionale di papirologia, vol. III, Napoli 1984, S. 1125–1133, hier S. 1131.

Der kürzlich neu edierte[45] Brief eines Vaters an seinen Sohn (Euhemeria; 2. Jh. n. Chr.) endet vor dem Abbruch in Z. 10–11 mit der Aufforderung: καὶ σὺ φιλοπόνησον | τ̣ὰ με[τρήμ]ατά σου ̣[, was übersetzt wird mit „you too try hard [to make] your payments …“. Die Abbildung[46] zeigt, daß von dem Epsilon in με[τρήμ]ατα höchstens eine minimale Spur vorhanden ist, eher sogar überhaupt nichts, während ich vom zweiten μ nach der Lücke noch Reste zu sehen glaube. Dies eröffnet die Möglichkeit einer Alternativergänzung, die mir im Kontext attraktiver erscheint, nämlich μ[αθή]μ̣ατα. Der in der Lücke vorhandene Platz wird dadurch gut gefüllt. Φιλοπονέω („fleißig etwas betreiben“) mit einem Akkusativobjekt ist normal (s. LSJ s.v.) und das Thema „fleißig lernen“ spielt in Briefen von Eltern oder ihren Kindern in den Papyri bekanntlich nicht selten eine Rolle. Beispiele mit Verwendung von φιλοπονέω bzw. sinnverwandtem προσκαρτερέω und μαθήματα sind z. B. P.Brem. 63, 24–25; P.Oxy. X 1296, 6–7; PSI I 94, 8–9; SB XXVI 16536, 6. 10.

Alle drei „Quittungen für φόρος προβάτων“, die in diesem Text (Euhemeria[47]; 152–153 n. Chr., s. unten) vereinigt sind, verwenden der Edition zufolge in den Datierungsformeln bei den Jahresangaben Ordinalzahlen, die in nachklassischer Zeit unerwartet sind [48]. So liest man in Z. 1 ἔτους τετάρτου καὶ δ[εκάτου, wo τεσσαρεσκαιδεκάτου zu erwarten wäre, in Z. 7 ἔτους πέμπτου καὶ δεκάτου, wo πεντεκαιδεκάτου üblich wäre, und in Z. 15 ἔτους ἕκτου καὶ δεκάτου anstelle von ἑκκαιδεκάτου. Eine Überprüfung der am Orte der Erstedition beigegebenen Abbildung[49] erweist jedoch alle drei Fälle als Fehllesungen. In Z. 1 steht nicht τετάρτου καὶ δ[εκάτου, sondern πεντεκαιδ[εκάτου, in Z. 7 steht wirklich πεντεκαιδεκάτου und in Z. 15 tatsächlich ἑ̣κ̣καιδεκάτου.

Für die erste der drei Quittungen bedeutet die Korrektur, daß sie nicht vom 11. Mai 151 stammt, wie man bisher annahm, sondern vom 11. Mai 152 n. Chr.

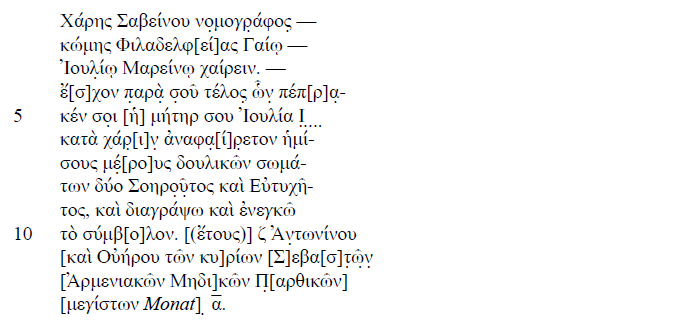

Das Studium der Abbildung ermöglicht aber auch eine weitere interessante Korrektur, nämlich bei der Lesung des Namens des Praktors, der laut der zweiten und dritten Quittung (und möglicherweise auch der ersten) die Steuer vereinnahmt hat. In Z. 10–11 und 18–19 ist transkribiert worden: διέγ(ραψε) [50] Διδύμ̣(ῳ) κ(αὶ) μετόχ(οις) | πράκ(τορσιν) Name des Zahlers; die Abbildung läßt jedoch deutlich über dem Iota von Διδύμ̣(ῳ) einen hohen waagerechten Strich erkennen, der eine Abkürzung anzeigt. Es ist hier also δι(ά) zu lesen, worauf der Name des Einnehmers (und seiner Kollegen) im Genitiv folgte, wie dies besonders in arsinoitischen Steuerquittungen sehr häufig der Fall ist. Die Suche nach „διέγραψε/διέγραψεν διά“ in der DDbDP liefert gegenwärtig rund 60 Ergebnisse für das Formular, welches den Praktor nicht als Empfänger, sondern als Vermittler der Zahlung an den Staat bezeichnet. Der Name des in SB XXII 15241 genannten Prakors muß recht kurz gewesen sein; er hat sicher mit einem Delta begonnen, aber υμ̣, was der Herausgeber danach transkribiert hat, ist nicht akzeptabel; man sieht vielmehr am ehesten ein zweites Delta, wobei sich eine Deutung des Befundes nicht aufdrängt. Hier helfen zwei Parallelen weiter, und zwar die beiden Steuerquittungen P.Stras. V 365 und 366, deren Herkunft unbekannt ist, die aber vom Juni/Juli 152 stammen, also aus demselben 15. Regierungsjahr wie die erste und die zweite Quittung des hier diskutierten Papyrus. In P.Stras. V 365, 3–4 lesen wir: διέγρ(αψε) δι(ὰ) Δ̣ι̣δᾶ | [καὶ μετόχ(ων) πρ]ακ(τόρων) Name, in 366,3–4: διέγρ(αψε) | [δι(ὰ) Δ]ι̣δ̣ᾶ κ̣α̣ὶ̣ μετ(όχων) πρακ(τόρων) Name. Die Vermutung liegt nun sehr nahe, daß auch in SB XXII 15241, 10 und 18 δι(ὰ) Διδᾶ gelesen werden muß.

Weil mir dies aber an der Abbildung nicht evident nachvollziehbar war, habe ich Paul Heilporn gebeten, die Originale der Straßburger Papyri mit dieser Abbildung zu vergleichen, in der Hoffnung, daß sich so mehr Sicherheit gewinnen lasse. Heilporn ist dieser Bitte bereitwillig nachgekommen, wofür ich ihm herzlich danke, und hat mir am 18.06.2015 durch E-Mail zusammen mit guten digitalen Abbildungen seine Beobachtungen mitgeteilt. Danach ist P.Stras. V 366 nicht hilfreich, weil die Schrift an der Stelle sehr verblaßt ist[51]; in P.Stras. V 365, 3 dagegen ist die Lesung δι(ὰ) Διδᾶ unausweichlich, und der Vergleich läßt erkennen, daß eine solche Lesung auch in SB XXII 15241, 10 und 18 möglich ist. Heilporn resümiert: „Je suis d’accord avec vous sur la coïncidence avec SB XXII 15241, où rien ne semble empêcher de lire Διδᾶ.“

Der Schreiber verwendet offenbar für die Kombination der Buchstaben δι neben der wohlbekannten, die er in P.Stras. V 365, 3 und SB XXII 15241, 10 bei δι(ά) eingesetzt hat, eine zweite, bei welcher das Iota in einem kurzen, das Delta rechts schließenden senkrechten Strichlein besteht, derart, daß die Verbindung δι das Aussehen eines Quadrats oder Trapezes annimmt. In SB XXII 15241, 10 und 18 bleibt fraglich, ob man nicht besser δι(ὰ) Διδ(ᾶ) καί transkribieren sollte; ich möchte aber nicht ausschließen, daß das Alpha in einem (undeutlichen) Verbindungsstrich zum Kappa von καί vorliegt, und würde daher auch hier δι(ὰ) Διδᾶ̣ καί für vertretbar halten, was ja in P.Stras. V 365, 3 offenkundig ist.

Insgesamt beweist der Vergleich der Schriften, daß derselbe Schreiber sowohl die Quittungen II und III von SB XXII 15241 als auch die beiden Straßburger Texte geschrieben hat. Letztere, deren Herkunft bislang unbestimmt geblieben war, stammen nach den neuen Erkenntnissen sicher aus Euhemeria [52].

Nach dem Erscheinen meines diesbezüglichen Aufsatzes[53] sind mir weitere Fälle bekannt geworden, in denen Numeralsubstantive im Zusammenhang mit Tagesdaten nicht erkannt worden sind und wo man daher fälschlich stattdessen Ordinalzahlen oder andere Formen ergänzt hat.

Übersehen hatte ich P.Lond. II 197 recto, 8 (S. 100): τ̣ῇ τετ̣ρατ[ηκ]αιεικ̣[οστῇ]; hierzu gibt es bei der Edition keine Korrektur und keinen Kommentar, aber die Tatsache, daß die Stelle im Register auf S. 406 von P.Lond. II unter τετρακαιεικοστός aufgenommen worden ist, verdeutlich, daß die Herausgeber die Form für eine Verschreibung von τῇ τετρακαιεικοστῇ gehalten haben. Dieser Gedanke war in der Frühzeit der Papyrologie, als man noch nicht über die Fülle von Texten verfügte, die wir heute kennen, verständlich, zumal die Herausgeber in demselben Bande, nämlich in P.Lond. II 180, 11 (S. 94), erstmals mit dem Wort τετρακεικοστόν für 1/24 konfrontiert waren[54]. Sofern richtig entziffert worden ist — eine Abbildung steht zur Kontrolle momentan noch nicht frei zur Verfügung —, muß man τ̣ῇ τετ̣ράτ[ι (l. τετράδι) κ]αὶ εἰκ̣[άδι] herstellen; ich vermute jedoch, daß auch τ̣ῇ τετ̣ράδ̣[ι κ]αὶ εἰκ̣[άδι] gelesen werden kann.

Zwei Fälle sind erst später publiziert worden: In BGU XX 2843, 1 sollte τετράδι καὶ ε]ἰκάδι statt τετάρτῃ καὶ ε]ἰκάδι ergänzt werden, und entsprechend in P.Mich. inv. 779, 5[55] τετ̣[ράδι] κ̣α̣̣ὶ̣ ε̣[ἰκά]δι statt τετ̣[άρτῃ] κ̣α̣̣ὶ̣ ε̣[ἰκά]δι.

Dieter HAGEDORN

Il papiro (Tebtynis; 166 d. C.) contiene un conto delle spese sostenute per i lavori di costruzione di un torchio vinario. La revisione del reperto, unitamente alla collocazione dei tre frammenti non trascritti nell’ed. pr. [57], ma visibili in P.Mil.Vogl. VII, tavv. IV e IV B, suggerisce nuove letture e, pertanto, la trascrizione del testo può essere così precisata:

col. I, l. 5[58]: ἀ̣ν[ὰ φ]ο̣ρ̣[άς. Qui si posiziona il frammento più piccolo e scritto solo sul recto, ove è leggibile la lettera ν.

col. III, ll. 43–49: ὑπουργοῦντ̣[ε]ς̣ ̣ ̣ [±3] ǀ ἐπ̣ισκά̣[πτοντες[59]] ἐργ(άται) β [±3] ǀ εἰσ̣π[± 4] ἐργ(άται) β̣ [±3] ǀ ι̅β̅ ὁμοίω̣[ς] ἐ̣ργ(άται) β [±3] ǀ ι̅γ̅ ὁμοί[ως] ἐ[ργ(άται) β [±3] ǀ χ̣(αλκοῦ) (δραχμαὶ) ρδ ǀ [͞ι]͞δ̣ λιθοφο̣ρ̣[οῦντες ὄνοι[60]. In questa sede è stato collocato il frammento più ampio.

La parte inferiore della colonna, a partire da l. 54, può essere così trascritta, inserendo anche le righe che l’editore definisce “in lacuna”, ma delle

quali in realtà restano tracce[61]:

[ ̣̅ ὁμοίως ὄν]οι δ (δραχμαὶ) η ǀ [± 5 ἐρ̣γ(άται) β] (ὀβολοὶ) ις ǀ [ ̣̅ ὁμοίως ὄ]ν̣οι δ (δραχμαὶ) η ǀ [± 5] ἐρ̣γ̣(άται) β (ὀβολοὶ) ι̣ς ǀ [ ̣̅ ὁμοίως]

ὄ̣ν̣ο̣ι̣ δ (δραχμαὶ) η ǀ [± 2] ̣ [±3] ἐ̣ρ̣̣[γ(άται)] β̣ [(ὀβολοὶ) ι]ς̣ ǀ [ ̣̅ ὁ]μ̣ο̣ί̣ω̣ς̣ [ὄνο]ι̣ [ ǀ [± 2] ̣ [±3 ἐρ̣γ(άται)] β̣ (ὀβολοὶ) ι̣ς̣ ǀ [ ̣̅

ὁμοί]ω̣ς̣ ὄν[ο]ι [ ǀ [± 5 ἐ]ρ̣γ̣(άται) β [(ὀβολοὶ)] ι̣ς̣ ǀ ͞ζ ὁ̣[μοί]ω̣ς̣ [ὄνοι δ (δραχμαὶ)] η̣ ǀ [±5] ἐρ̣̣γ̣(άται ) [β (ὀβολοὶ)] ι̣ς̣ ǀ ͞η [ὁμοίως ὄνοι]

δ̣ [(δραχμαὶ)] η̣ ǀ [ ±5] ἐρ̣γ̣(άται) β̣ [(ὀβολοὶ)] ι̣ς̣ ǀ [͞θ ὁμοί]ως ὄνο̣ι δ (δραχμαὶ) η ǀ [± 5] ἐρ̣γ(άται) β̣̣ [(ὀβολοὶ)] ις ǀ [͞ι ὁμοί]ω̣ς ὄνο̣[ι δ]

(δραχμαὶ)] η ǀ [±5 ἐ]ρ̣̣γ(άται) β̣ [(ὀβολοὶ) ι]ς̣ ǀ ͞ι̣͞α̣ [ὁμοί]ω̣ς̣ ὄν[οι δ (δραχμαὶ)] η ǀ [± 5] ἐ̣ρ̣γ(άται) β [(ὀβολοὶ) ις] ǀ ͞ι[͞β ὁμοίως] ὄν[ο]ι ̣

(δραχμαὶ) ̣ ǀ [± 5 ἐρ]γ̣(άται) β̣ [(ὀβολοὶ)] ι̣ς̣.

col. IV: all’inizio della colonna, sopra la l. 68, c’erano verosimilmente sette linee. Le prime due di queste sono completamente perdute. Alla terza appartiene probabilmente il frammento 3[62], ove si può leggere: ̣̅ [ὁ]μο[ίως. Le tre linee successive sono del tutto perdute. Nella settima linea, antistante a l. 68, si legge: [± 15] (δραχμαί).

Dopo la l. 77 una linea è caduta in lacuna.

l. 79: λ̣ιθ̣οφ[ο]ρ̣[οῦντε]ς̣ ὄ̣[ν]ο̣ι θ (δραχμαὶ) ιη. Successivamente una riga è persa in lacuna.

col. VI, l. 106: [±5] (δραχμαὶ) ι̣η.

l. 112: ι̣ζ e non ζ.

col. VII, dopo l. 118 le 10 righe non trascritte nell’ed. pr. possono essere così lette: κ̣α̣ὶ ἐ̣ρ̣γ̣( ) [ ǀ 2 linee in lacuna ǀ ̣̅ ὁμ[ο]ί̣ω̣ς̣

ὄ̣ν̣[οι ǀ κ̣αὶ ἐ̣[ρ̣]γ̣(άται) [β̣ (ὀβολοὶ) ι]β̣ ǀ una linea in lacuna ǀ κα̣ὶ [ἐ]ρ̣γ̣(άται) β̣ (ὀβολοὶ) ι̣β ǀ ̣̅ ὁ[μ]ο̣ί̣ω̣ς̣ ὄ[νο]ι̣ β (δραχμαὶ) δ ǀ κ̣[α]ὶ

[ἐ]ρ̣γ̣(άται) β̣ (ὀβολοὶ) ιβ ǀ

[ ̣̅ ὁμοίως ὄνοι] β̣ (δραχμαὶ) δ.

l. 124: ͞ιε e non ͞ε̣.

Dopo l. 125: qui sono posizionati i frr. 2 e 3. Sul verso del fr. 2 si legge: ͞κ̣ [ǀ ̣ [±3] ̣[ ǀ ͞κ͞α [ ; su quello del fr. 3 vi è solo una lettera che rassomiglia a ι.

Federica MICUCCI

BGU IV 1200 is the draft of a petition in which priests from Bousiris in the Heracleopolite nome ask the prefect Publius Octavius to investigate two officials, who according to the priests withheld an annual income of 100 artabas from them over a period of ten years (years 20–29 of Augustus). The priests claim that the two officials were bribed by villagers. In lines 21–22 the editor reads as follows:

The only possible supplement is (κατα)δυνα]στευόμενοι: “(the officials) being ruled by them (the villagers).” For διαμωλύω LSJ lists only this passage, where the editor suggested “sie machten uns mürbe” in a note. The verb has now also turned up in P.Bingen 58.15–16, a contemporary petition, where the petitioner claims that her tenants τὸν χρόνον διαμωλύουσι, “waste time (= drag their feet).” Such a meaning would fit BGU IV 1200 but not require a supplement ἡμᾶς at the end of line 21. If we tentatively supplement τὸν χρόνον instead, in combination with δυνα]στευόμενοι, we get: “and until now they (the officials) have wasted time (= dragged their feet) under their (the villagers’) influence.”

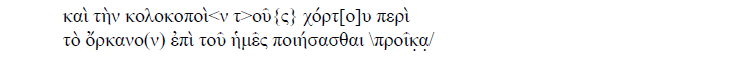

In this fourth-century contract the additional stipulation in lines 16–17 has not yet been satisfactorily explained in the re-edition. It is presented there as follows:

Κολοκοποί<ν> here is taken to stand for καυλοκοπήν, the cutting of stalks. This (or καυλοκοπίαν, earlier suggested in BL 1.110) occurs nowhere else, and to the best of my knowledge stalks do not occur in combination with χόρτος, hay. I propose an alternative reading that is slightly less interventionist than that of the re-editor R. P. Salomons (at the same time undoing some of the other changes over against the ed. pr. introduced by him):

I take κολοκοποιοῦς here to stand for κολοβοφυοῦς. The interchange of υ and οι is banal, and even π for φ between vowels is not uncommon (Gignac, Gram. 1.93; cf. πασήλων for φασήλων in line 7). κ for β is more difficult, but in some hands the two letters look alike. Note that P.Cair.Preis. 38 is a copy (in one hand) made from an original where the subscription by one of the parties may have been hard to read. The subscription is in any case faulty, and I assume κοπήν has fallen out: “and on condition that we perform the <cutting> of the short-growing hay around the irrigation machine(s) free of charge.” Short-growing hay is typical of the Hermopolite nome, if we go by the few occurrences of this adjective that have so far turned up (BGU XII 2172.12–13; 2198.11 and 15; and P.Horak 9.6, where κολοβοφυτους seems to mix κολοβοφυοῦς and κολοβοφύτου). That P.Cair.Preis. 38 comes from the Hermopolite nome was suggested by the re-editor, because the man who wrote the original subscription, Βῆκις Βίωνος, may well be the same as in P.Eirene I 8.r.13, also from the fourth-century Hermopolite nome.

P.Genova V 204, provisionally entitled “composizione di una lite,” is a third/fourth-century fragment, which seems to contain, at least from line 3 onwards, a report of proceedings, in which one of the speakers is introduced twice. The editor transcribes the relevant portions of the text as follows:

Line 6: ] . . . λ˙ αε̣γι/

Line 7: ]λ˙ αε̣γι/

In both cases, a verb of saying would be absent or lost in the lacuna. Reports of proceedings without a verb of saying are more typical of the early Roman period (see R. A. Coles, Reports of Proceedings in Papyri, Brussels 1966, 40–46).

Instead of alpha I prefer lambda in both cases. Before the first lambda in line 6 I see an upsilon (cf. ed. ad loc.: Ἰυλ) and before that a phi (not just an iota). Reading φυλ for -φύλ(αξ) seems unavoidable, and λεγι/ must in that case be for λεγι(ῶνος). In combination with φυλ( ) this suggests ὁπλο]φύλ(αξ) λεγι(ῶνος) in line 6 and ὁπλοφύ]λ(αξ) λεγι(ῶνος) in line 7. ὁπλοφύλαξ is Greek for armorum custos. The Greek has so far occurred only in O.Berenike II 131.5 (a first-century papyrus) and a few Greek inscriptions from outside Egypt (Ramsay, Cities and Bishoprics, p. 380, no. 211, and p. 381, no. 214, both for equites). Armorum custos appears in Greek as ἀρμοκούστωρ in Ch.L.A. XLII 1207.17, O.Bodl. II 2022.1, and no doubt also in BGU I 344.14 (ed. Μαρῖνος αρμοκ( ); cf. BL II 2, p. 15) and abbreviated to ἀρμορου in Rom.Mil.Rec. 76.15.8. Armorum custos occurs more frequently in Latin, e.g. in P.Diog. 1.17: armorum cus(tos) and Rom.Mil.Rec. 129.6: a(rmorum) c(ustos), especially in inscriptions, including from Alexandria: CIL III 14138(2) (AE 2003, 1841) is a third-century dedication for M(arcum) Aurelium Neonem quondam mili(tem) a(rmorum) c(ustodem) leg(ionis) II Tr(aianae) Fortis Germani(cae) Severianae.

From a scan it appears that the correct reading in line 3 of SB XIV 11591, an early fourth-century account, is not εἰς τὸ πλοῖον but εἰς πλοῖον. This expression without the article occurs about twice as frequently as with the article.

In lines 7–8 the reading appears to be εἰς τὴ̣[ν] ὑπη̣[ρεσίαν] τῷ πραιπ(οσίτῳ), not τοῦ πραι[π(οσίτου)]. The expression εἰς τὴν ὑπηρεσίαν is followed by τῷ πραιποσίτου in the contemporary SPP XX 75.1.28, also from Hermopolis. In the related SB XIV 11592.7–8, εἰς τὴν ὑπηρεσίαν τ̣ο̣ῦ πραιποσίτου, the reading τ̣ο̣ῦ at the end of the line is uncertain to judge from the plate in the editio princeps.

In lines 27–28 of SB XIV 11593, also from fourth-century Hermopolis, ἐκ κελεύσεως τοῦ | π̣οστου ἐξάκτορος makes no sense. The plate in the editio princeps allows reading ως τοῦ instead of π̣οστου at the beginning of line 28, a case of dittography from the end of line 27.

Peter van MINNEN

[1] On the toponyms mentioned in this papyrus and their Apionic connections, see my Rural Settlements of the Oxyrhynchite Nome (Version 2.0; Leuven, Köln 2012; downloadable from <http://www.trismegistos.org/top.php>) under the relevant entries.

[2] A photograph of the papyrus is available online via HGV. I have inspected the original in the Sackler Library, Oxford.

[3] ‘Non è da scartare l’eventualità che sia da leggere, qui, Ταρο]υ̣θίνου, lo stesso nome che compare (anche se cancellato dallo scriba) al r. 28 del documento.’

[4] R. A. Coles, Location-List of the Oxyrhynchus Papryi and of Other Greek Papyri Published by the Egypt Exploration Society, London 1974, 39.

[5] http://www.trismegistos.org/ghostnames/index.php.

[6] F. Preisigke, Namenbuch enthaltend alle griechischen, lateinischen, hebräischen, arabischen und sonstigen semitischen und nichtsemitischen Menschennamen , Heidelberg 1922; D. Foraboschi, Onomasticon alterum papyrologicum, Milan 1971. The name section of Trismegistos and the Papyrologische Wörterliste online will probably play a similar roll in the future, though thus far papyrologists still tend to refer to Preisigke and Foraboschi for parallels.

[7] See W. Clarysse, Artabas of grain or artabas of grains?, BASP 51 (2014) 104 n. 13.

[8]

L. Berkes, Bemerkungen zu Papyri XXVI (Korr. Tyche), Tyche 28 (2013) 203 ;

D. Hagedorn, dans: T. Kruse, Urkundenreferate 2010, APF 59 (2013) 227–228 (ci-après Hagedorn).

[9] La formule de politesse des l. 2–3, καὶ τὴν ἐποφ̣[ειλομένην προσκύνησιν τῇ ὑμετέρᾳ] | πατρικῇ ἁγιοσύνῃ (ἁγιωσύνη̣), est acceptable, mais il en résulte une difficulté syntaxique par rapport à ce qui précède, aussi les éd. corrigent-ils en μετὰ τῆς ἐποφειλομένης προσκυνήσεως (app.). On peut éviter cette intervention, en insérant, sur le même plan que le γράψαι du début de la l. 2, l’infinitif ποιήσασθαι, l. 2, devant τῇ ὑμετέρᾳ. Cette conjecture conduit à ajouter jusqu’à 10 lettres par ligne.

[10] Voir pour ce sens P.Oxy. XVI 1838, 2.

[11] La restitution de la première personne par les éd. est probable au vu de la l. 20.

[12] Pour les dégâts causés par les souris sur les comestibles, voir par ex. P.Oslo. 52, 5, P. Lond. VII 2033, 4 et P.Flor. II 150, 4–5. Le cuir lui-même peut être atteint : P.Panop.Beatty 1, 391.

[13] Voir LexByzGräz VI, s. v. Dans le champ animalier, LSJ n’enregistre ποντικός qu’au sens de « belette ».

[14] Bemerkungen zu Papyri XXIV (Korr. Tyche) , Tyche 26 (2011) 290.

[15] Eine ungewöhnliche koptische Schreibhelferformel in P.Gen. IV 189 und Korrekturen zum griechischen und koptischen Teil der Urkunde , ZPE 177 (2011) 237–239 (je lirais à la l. 3 le nom Νααραοῦ au lieu de Νααραῦ).

[16] Ils ont à juste titre corrigé la l. 5 en υἱοῦ Ψέει πρε(σβυτέρου), au lieu de υἱο̣ῦ Ψεειτάρου. Il est curieux qu’un prêtre Ψέειος revienne à plusieurs reprises dans l’acte d’arbitrage arsinoïtain du VIIe s. P.Gen. IV 181, 2, [5], 8, 9. Les éd., n. 2, ont rapproché ce personnage du prêtre homonyme de SPP VIII 929, 1.

[17] C’est ici le lieu de remercier P. Schubert qui m’a aimablement procuré une image numérique du texte et a bien voulu discuter de ma conjecture.

[18] Bemerkungen zu Papyri xxvi (Korr.Tyche) , Tyche 28 (2013) 210.

[19] E. Battaglia, ‘Artos’. Il lessico della panificazione nei papiri greci, Milano 1989, 195–197.