W. Graham Claytor

A Decian Libellus at Luther College (Iowa)*

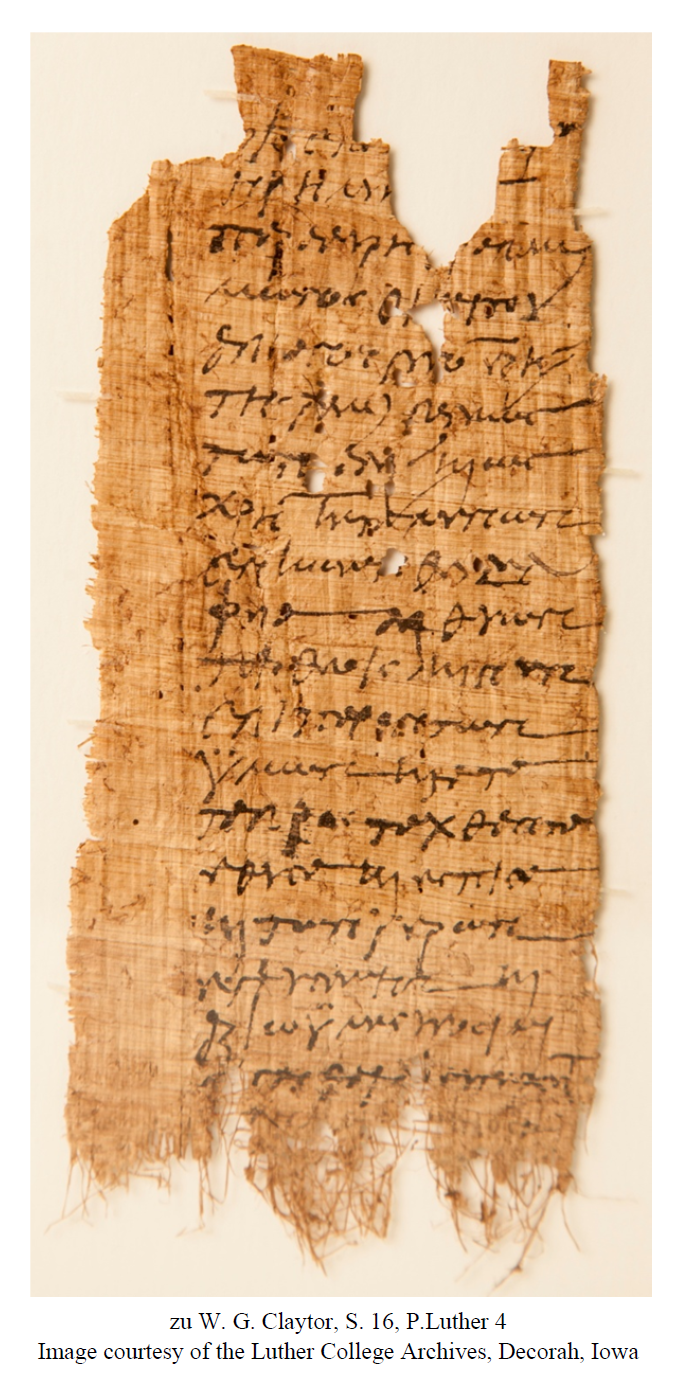

Plate 6

This libellus was recently rediscovered at Luther College (Decorah, Iowa) during the cataloging of papers belonging to the late Orlando W. Qualley (1897–1988), a professor of Classics and longtime dean of the college.[1] In 1924–1925, Qualley spent seven months in Egypt as part of the University of Michigan’s excavation team during the first season at the Fayum village of Karanis. His entire sojourn is documented in a remarkable trove of letters sent back to his then-fiancée, from which we learn that he purchased a small lot of ten papyri on October 28, 1924 from the Cairo banker and antiquities dealer Maurice Nahman.[2] Nine of these papyri [3] were accessioned along with Qualley’s papers in 1986 by the Luther College Archives, where they lay dormant until January, 2014. After rediscovery, the papyri were sent to the University of Michigan for conservation and preliminary study. [4]

This papyrus joins a well-established corpus of documents stemming from the emperor Decius’ empire-wide order to sacrifice issued shortly after his accession in 249 CE.[5] The nature, motives, and effects of this decree have been widely discussed,[6] with the papyri playing a pivotal role since the publication of the first libellus in 1893. [7] In particular, they undermined the traditional view that the decree pertained only to suspected Christians.[8] The turning point was the appearance of a libellus submitted by a priestess of the crocodile god Petesouchos (an unlikely guise even for a wary Christian) and it is now generally held that the decree was universal. [9] More recently, the debate has centered on the nature of Decius’ religious policy and, specifically, whether the decree was intended to initiate a persecution of Christians. In my view, the overriding purpose of this admittedly unprecedented measure was to reaffirm the empire’s special relationship with the gods through a universal display of traditional piety; Decius’ more particular desire for legitimation of his rule and the loyalty of his subjects cannot be discounted.[10] That the emperor was aware of the difficulties this measure would present for Christians seems likely enough, but the general nature of the decree and the fact that it was not followed up with more targeted measures suggest that Decius’ intent was not fundamentally anti-Christian, in contrast to the persecutions of later emperors.

The Egyptian libelli are our only documentary sources resulting from the decree, but written certification of sacrifice was also required in Rome and North Africa, which suggests that the policy was universal.[11] Just as in the case of the Roman census, however, the actual implementation of the decree was left to provincial authorities, who in turn entrusted the task to civic bodies and other local authorities. [12] In Egypt, the commissioners were often called οἱ ἐπὶ τῶν θυσιῶν ᾑρημένοι, “those selected to oversee the sacrifices,” and were drawn from the local curial class (see ll. 1–2 n.).

The libelli take the form of hypomnemata, common to census and property declarations, declarations of birth and death, and other ἀπογραφαί.[13] The libellus P.Oxy. LVIII 3929 is in fact entitled ἀπογρ(αφὴ) Ἀμοϊτᾶ μητ(ρὸς) Τααμόϊτ(ος) on its verso, an important witness to how these documents were classified by the local administration. After the address and the identification of the petitioner, the documents invariably contain a statement of sacrifice and a request for the presiding authorities to certify the action. There follows the certification, “we saw you sacrificing,” and, in many cases, a subscription in the hand of one of the officials. Extant copies suggest that the normal procedure was to draw up the libellus in duplicate, with one copy being returned to the petitioner and the other archived. This multi-stage process and the stress on the commissioners’ visual confirmation of the act likely reflect the decree’s insistence on the personal appearance and participation of the entire empire in this monumental offering to the gods.[14]

Like the vast majority of extant examples (34 of 47), the Luther College document was issued to a resident of Theadelphia, a village in the southwest of Egypt’s Fayum region. It has long been suspected that most or all of the Theadelphian libelli were found together in the village, particularly since 21 of them were acquired as a group by Hamburg’s Staatsbibliothek (now Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek). [15] This group may have been retained by one of the presiding officials because the parties failed to retrieve their documents, or perhaps represent the remnants of an official archive.[16]

The Luther College libellus was submitted by Aurelius Sarapammon, who is identified as a servant (οἰκέτης) of the well-known Alexandrian magistrate Aurelius Appianus. Sarapammon is in all likelihood a camel driver known from the archive of Heroninus, Appianus’ estate manager in Theadelphia (see ll. 3–4 n.). The fragmentary bottom of the papyrus contains the beginning of the attestation of the presiding officials, Serenus and Hermas, [17] after which Hermas may have written his distinctive signature, with large, awkward letters. The last element would have been the date of the certification, probably in June, 250 CE.[18]

This papyrus is a medium-brown color with dark fibrous inclusions. It is frayed at the bottom, but otherwise mostly complete, except for some damage at the

top, particularly along the right fold line. Enough is preserved to determine that its top margin is 1 cm. The left margin is about 1.75 cm and the writing

reaches the right edge, often with the help of filler strokes. The papyrus was folded lengthwise twice. The writing is with the fibers and the verso is

blank. Digital images of the front and back can be found here: https://www.luther.edu/archives/

research/digital-collections/papyrus/images (accessed 7 Oct., 2015).

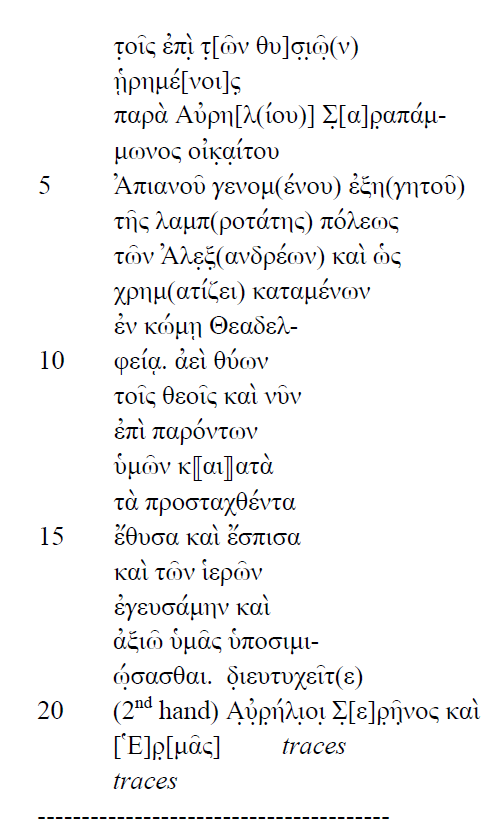

1 [θυ]σ̣ι̣ω̣ pap. 3 αυρη[λ] pap. 4 l. οἰκέτου 5 γενομ, εξη ̅ pap. 6 λαμ) pap. 7 αλεξ / pap. 8 χρημ pap., l. καταμένοντος 13 υμων pap. 15 l. ἔσπεισα 16 ιερων pap. 18 υμασ pap. 18–19 l. ὑποσημειώσασθαι 19 δ̣ιευτυχειτ pap.

“To those who have been selected to oversee the sacrifices, from Aurelius Sarapammon, servant of Appianus, former exegetes of the most-illustrious city of the Alexandrians, and however he is styled, residing in the village of Theadelphia. Always sacrificing to the gods, now too, in your presence, in accordance with the orders, I sacrificed and poured the libations and tasted the offerings, and I ask that you sign below. Farewell.

(2nd hand) We, the Aurelii Serenus and Hermas, saw you sacrificing (?) …”

1–2 τ̣οῖς ἐπὶ̣ τ̣[ῶν θυ]σ̣ι̣ῶ̣(ν) | ᾑρημέ[νοι]ς̣. αἱρέομαι is commonly used of those “selected” for curial liturgies, [19] generally by a decree of the town council.[20] The commissioners charged with overseeing village sacrifices were therefore likely drawn from the ranks of the curial class; one is specifically styled as a πρύτανις, or president of the town council (P.Ryl. I 12). See further Knipfing, Libelli (n. 5), 350–353.

3–4 Αὐρη[λ(ίου)] Σ̣[α]ρ̣απάμ|μωνος. There are two men of this name attested as οἰκέται of Appianus’ estate: one is an ox-driver working on the φροντίς (estate division) of Euhemeria and the other is a camel-driver employed in Theadelphia. Given that our Sarapammon is resident in Theadelphia, an identification with the camel-driver is more likely. Moreover, he received wages in Theadelphia just a few months after this libellus was issued ( P.Prag.Varcl II 2 = SB VI 9408 (1), September, 250).

4 οἰκ̣α̣ίτου (l. οἰκέτου). This term normally means “slave,” but D. Rathbone has collected evidence that points to the free status of οἰκέται employed on Appianus’ estate (Economic Rationalism and Rural Society in Third-Century AD Egypt, Cambridge 1991, 106–115). One of the more telling indications is the gentilicium Aurelius applied to the οἰκέτης Euprodokios in the certificate SB I 4450, which is now paralleled by the author of our libellus, Aurelius Sarapammon. Although technically free, the οἰκέται were clearly dependent laborers, maybe even attached to the estate for life (Rathbone, Economic Rationalism, 115). “Perhaps the use of the word οἰκέτης,” K. Harper concludes in the latest discussion, “reflects the shadowlands of legal status at the point where brutal poverty met total dependence” (Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425, Cambridge 2011, 518).

5–8 Ἀπιανοῦ γενομ(ένου) ἐξη(γητοῦ) | τῆς̣ λαμπ(ροτάτης) πόλεως | τῶν Ἀλεξ(ανδρέων) καὶ ὡς χρημ(ατίζει). This is Aurelius Appianus, the Alexandrian magistrate whose Fayum estate is well known to us through the archive of Heroninus, his estate manager in Theadelphia (see Rathbone, Economic Rationalism, 44–52). The omission of his gentilicium Aurelius is surprising and probably an accident, since his employee Sarapammon and the two officials are styled as Aurelii, as is Appianus himself in the other libellus issued to one of his employees (SB I 4450.4). The omission of βουλευτής, on the other hand, can probably be understood as an economical abridgement of his titles, since all Alexandrian ἐξηγηταί were members of the city council (it is likewise lacking in SB I 4450). Similarly, in tax receipts on ostraka from the archive, Appianus is styled simply as a former ἐξηγητής.

8–10 καταμένων | ἐν κώμῃ Θεαδελ|φείᾳ. Aurelius Sarapammon’s idia is not mentioned, but he was living and working in Theadelphia at the time (cf. ll. 3–4 n.).

13 κ⟦αι⟧ατὰ. The scribe wrote a quick καί (cf. those in ll. 7, 11, 15, 16, 17), then appears to have drawn a horizontal line through the αι, indicating a deletion, before continuing with the rest of the correct word, κατά. One might also interpret this horizontal line as an attempt to make a tau out of the iota, although this would leave a superfluous τα at the beginning of l. 14, which would have to be removed: κατὰ τὰ | {τα} προσταχθέντα.

13–14 κ⟦αι⟧ατὰ | τὰ προσταχθέντα. This phrase refers to Decius’ edict (called τὸ βασιλικὸν πρόσταγμα by Dionysius of Alexandria: Euseb., Hist . eccl. 6.41.1.), as confirmed by the expanded formula in P.Oxy. XII 1464.6: [κατ]ὰ τὰ κελευσθέντα ὑπὸ τῆς θείας κρίσεως, “in accordance with the orders of the divine (= imperial) decree.” Cf. P.Lips. II, p. 235.

16 ἱερῶν. This variation on ἱερείων is also found in P.Oxy. IV 658.1 and 12, SB I 4450.12, SB I 4452.10, and P.Mich. III 158.11–12.

- - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -

Departement Altertumswissenschaften |

W. Graham Claytor |

* I would like to thank the Luther College Archives for permission to publish this document, as well as Sasha Griffen and Sarah Wick for coordinating with the University of Michigan. I am particularly grateful to Prof. Wilfred Bunge for providing information on the Luther College Papyri and for his generous transcription of Qualley’s letters (see n. 2). I also thank David Potter, who commented on a draft of this work and offered his thoughts on the libelli and Decius’ reign, and Julianna Paksi for proofreading the manuscript.

[1] The story is detailed in “Ancient Egyptian papyri discovered at Luther College,” Feb. 21, 2014

(https://www.luther.edu/headlines/?story_id=533743, accessed 7 Oct., 2015). Information on Qualley and the papyri can be found at Luther College’s

online exhibit “The Orlando W. Qualley Papyrus Collection:” https://www.luther.edu/archives/research/digital-collections/

papyrus (accessed 7 Oct., 2015).

[2] Qualley to Wollan, October 29, 1924. The letters are in the possession of Prof. Wilfred Bunge of Luther College, who has transcribed and edited them. They can be consulted at https://www.luther.edu/archives/assets/Qualley_Log_1924_25.pdf (accessed 7 Oct., 2015).

[3] One papyrus has gone missing. Described by Qualley as “one little one tied up and sealed just as perfectly preserved as can be” (Qualley to Wollan, October 29, 1924), a later letter reveals that it was unrolled in Ann Arbor in early 1954 under the supervision of Enoch Peterson, although its contents proved disappointing in some way (Qualley to Peterson, March 27, 1954, “The Papers of O.W. Qualley,” Luther College Archives, Box 6, Folder 6 [314-76-63]).

[4]

The edition below is based on autopsy. Marieka Kaye and Layla Lau-Lamb were responsible for conservation, which is outlined here:

https://www.luther.edu/archives/research/

digital-collections/papyrus/conservation (accessed 7 Oct., 2015). Descriptions and images of the other papyri can be viewed at

https://www.luther.edu/archives/research/digital-collections/

papyrus/images/ (accessed 7 Oct., 2015). These are being edited by the author and Brendan Haug.

[5] P.Lips. II 152 was the most-recently published. The editor, Reinhold Scholl, includes an up-to-date list of the 46 libelli published prior to the present document and a detailed discussion of the corpus with earlier bibliography (pp. 226–241). The groundwork on the texts was laid by P.M. Meyer, Die Libelli aus der Decianischen Christenverfolgung, Berlin 1910, and J.R. Knipfing, The Libelli of the Decian Persecution , The Harvard Theological Review 16.4 (1923) 345–390. Recent overviews of the texts and the implementation of Decius’ edict in Egypt can be found in A.M. Luijendijk, Greetings in the Lord: Early Christians and the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, Cambridge 2008, 157–174 and L.H. Blumell, T.A. Wayment, Christian Oxyrhynchus: Texts, Documents, and Sources (Second through Fourth Centuries), Baylor 2015, 373–393 (I thank Lincoln Blumell for providing me with an advance copy of this chapter).

[6] For a comprehensive and cogent overview, see J. Rives, The Decree of Decius and the Religion of Empire, JRS 89 (1999) 135–154. Other works of note published in the last 30 years include H.A. Pohlsander, The Religious Policy of Decius, ANRW II.16.3 (1986) 1826–1842; D.S. Potter, Prophecy and History in the Crisis of the Roman Empire, Oxford 1990, 42–43 and 261–267; R. Selinger,The Mid-Third Century Persecutions of Decius and Valerian, Frankfurt a. M. 2002; and B. Bleckmann, Zu den Motiven der Christenverfolgung des Decius, in: K.-P. Johne, T. Gerhardt, U. Hartmann (edd.), Deleto paene imperio Romano. Transformationsprozesse des Römischen Reiches im 3. Jahrhundert und ihre Rezeption in der Neuzeit, Stuttgart 2006, 57–71. See also A.R. Birley, Decius Reconsidered, in: E. Frézouls, H. Jouffroy (edd.), Les empereurs illyriens: actes du colloque de Strasbourg (11–13 octobre 1990), Strasbourg 1998, 57–80.

[7] F. Krebs, Ein Libellus eines Libellaticus vom Jahre 250 n. Chr. aus dem Faiyum, Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin (1893) 1007–1014, now BGU I 287 = W.Chr. 124.

[8] This view was so ingrained that Krebs (previous n.) simply assumed that the author of his text was a lapsed Christian, a libellaticus.

[9] The papyrus is W.Chr. 125, originally published by E. Breccia in 1907. Cf. Knipfing, Libelli (n. 5), 361–362. Dissenters: P. Keresztes, The Decian libelli and contemporary literature, Latomus 34 (1975) 761–781 and R.L. Fox, Pagans and Christians, Harmondsworth 1986, 455–457.

[10] Cf. D.S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395, London, New York, 22014, 139 and Bleckmann, Christenverfolgung (n. 6), 66.

[11] Cypr., Ep. 30.3.1 and 55.14.1. Cf. Rives, The Decree of Decius (n. 6), 141.

[12] On the provincial census, see now W.G. Claytor, R.S. Bagnall, The Beginnings of the Roman Provincial Census: A New Declaration from 3 BCE, GRBS 55.3 (2015) 637–653.

[13] Rives, The Decree of Decius (n. 6), 149–150 shows how the implementation of Decius’ decree in Egypt followed established bureaucratic procedure (cf. already Potter, Prophecy and History [n. 6] 43 and 262, n. 174).

[14] I thank David Potter for this observation.

[15] The Hamburg papyri and most of the other Theadelphian libelli were acquired before World War I, whereas the pair of Michigan libelli (P.Mich. III 157 and 158) and the Luther College libellus were acquired in 1920 and 1924 respectively.

[16] See further W. Clarysse, Decian Libelli (Version 2), Leuven Homepage of Papyrus Collections (2013), www.trismegistos.org/archive/331 (accessed 7 Oct., 2015).

[17] On whom see P.Lips. II, pp. 235–237.

[18] The earliest and latest dated libelli are June 4 and July 14, but besides these outliers all others fall between June 12 and 27: P.Lips. II, p. 234. It would be worth checking whether any of the fragmentary lower parts of libelli in the Hamburg collection join with the Luther College papyrus.

[19] N. Lewis, The Compulsory Public Services of Roman Egypt, Florence 1997, 58.

[20] The expanded phrase is αἱρεθεὶς ὑπὸ τῆς κρατίστης βουλῆς. Cf. e.g. P.Tebt. II 403.10–12 (215/216 CE): αἱρεθέν[των] ὑπὸ τῆς κρατίστη[ς βουλῆς] ἐπὶ ὄξους ἀννών[ης.