R O D N E Y A S T — R O G E R S. B A G N A L L

New Evidence for the Roman Garrison of Trimithis

Plates 1–3

Paul Kucera has recently surveyed the evidence for the Roman fort at el-Qasr in the Dakhla Oasis.[1] Largely concealed by the later buildings of the town, but partly re- vealed by excavations in recent years, this roughly 58 × 58 m fort can be identified as the home base of the ala I Quadorum, said by the Notitia Dignitatum (31.56, p. 65 Seeck) to have been stationed at Trimithis. The city of Trimithis is itself 2 kilometers to the south-southwest of el-Qasr, at the site today called Amheida[2] (pl. 1). The remains of the fort are consistent with its belonging to the same horizon of fort- building seen at, for example, el-Deir in the Kharga Oasis and Dionysias (Qasr Qarun) in the Fayyum. A preliminary examination of ceramic deposits in connection with the walls indicates a third to fifth-century date. A late fourth or early fifth- century Coptic ostrakon found in association with the wall refers to the “imperial fort”, showing that this is how it was referred to locally.[3] On the basis of the archaeo- logical evidence and the parallels, Kucera argues that the fort at el-Qasr was part of Diocletian’s fort-building program and dates to the same period as el-Deir and as Qaret el-Toub in Bahariya.[4] Kucera also collects a number of references from the Greek documents found at Kellis (Ismant el-Kharab) to a military installation, consistently called “the castra” (τὰ κάστρα) without further specification. In order to provide more precise locational information, he refers also to an unpublished dipinto on the wall of a room in a building at Amheida that mentions a member of, probably in fact the commander of, the “camp of Trimithis.” In the present article we publish this dipinto. This is, how- ever, not the only reference to military personnel in the finds from Amheida. At the time Kucera’s article went to press, the first volume of the ostraka from the ex- cavations (O.Trim. I) had not yet appeared, so he was unable to refer to the relevant material there.[5] Now that the second volume of ostraka is complete, we are able also to cite with publication numbers additional texts from it.[6]

The ostraka in the two volumes even taken together give us at best a few glimpses of the imperial military presence, rather than any sort of systematic picture. Nonethe- less, they make it clear that, as we would have expected, the garrison of Dakhla was more complex than the soldiers of one unit. That the ala I Quadorum had its head- quarters in Trimithis is not to be doubted, and the ala, along with a decurion, is mentioned in O.Trim. I 73. But indications of other units are also present. O.Trim. II 525 states that the locally-collected annona is destined for “the Tentyritai.” The Tentyrites were horse-mounted archers stationed in the valley at Tentyra, outside the modern town of Dendera.[7] The same unit seems to be referred to in an ostrakon from the agricultural settlement of ‘Ain el-Gedida, near Kellis, which reports a payment εἰς ἀννῶναν τῶν ἐν Μώθι ἀγγαρευόντων ἱπποτοξοτῶν “for the annona of the horse-arch- ers stationed in Mothis.”[8] Tentyrites are also known to have been in Kysis (Douch, in the Kharga Oasis).[9]

In O.Trim. II 528, an optio of Asphynis (ὀπτίων Ἀσφύνεως) named Alexandros receives an annona payment in barley. He will have been a member of the legio II Traiana, known from P.Col. VII 188, a document recording the will of a centurion of a cavalry vexillatio of the legio II Traiana stationed at the village of Asphynis in the Latopolite nome in 320 under the command of a praepositus named Decentius. From the Trimithis ostrakon we may deduce that a detachment of the legio II Traiana was at the time in Dakhla. The unit is referred to in the Not. Dig. Or. 31.40 (p. 64 Seeck) as the equites felices Honoriani, Asfynis and appears in the register just before the ala prima Abasgorum of Hibis in the Kharga Oasis.[10] It is therefore not surprising to find soldiers from Asphynis also in ostraka from Kysis in the south of the Kharga Oasis.[11]

The ostrakon mentioning the optio Alexandros refers to Serenos, the owner of the house (B1) just outside of which the text was deposited during its last phase, and it can thus be dated to ca. 350–370 with some confidence. It is a receipt issued to Serenos for a delivery of annona to Alexandros in the month of Thoth. The ostrakon that refers to the Tentyrites was found in Room 22, part of the northern appendages of the large house. It is a receipt for annona paid in Phaophi, also by Serenos. Both of these receipts are signed by Sarapion, who in II 525 is identified as an exactor, an

official who became responsible for the collection of imposts like the annona as a result of tetrarchic reforms.[12]

A camelarius receiving barley and wine for the adventus of a centurion appears in O.Trim. I 322. We cannot say with certainty what unit the centurion belonged to, but dromedarii were stationed at three locations in Egypt, two of them linked to the oasis circuit. Kucera has suggested the units stationed at Psinabla and Prektis in the Nile valley as plausible sources for the dromedarii attested in ostraka from Douch, and the same sources are likely for the man found at Trimithis.[13]

Given the economic character of most of the Trimithis ostraka, it is not surprising that the bulk of the references to the military are concerned with their supply, the annona militaris. A key official involved in keeping the records of military provisions is the actuarius, who appears in I 37.1 and I 329.4. In the former, he has 8 maria of oil registered against his name, while in the latter, he writes to a pronoetes giving orders to furnish barley for the annona of someone in Mothis.[14]

Other military personnel mentioned, in all cases receiving provisions, are a

singularis in I 294.5 (order or receipt for the value of oil), the scribae in I 41 and I

292 (receive hay, barley),[15] and a stationarius in I 293.3 (receives barley).

Amheida Dipinto

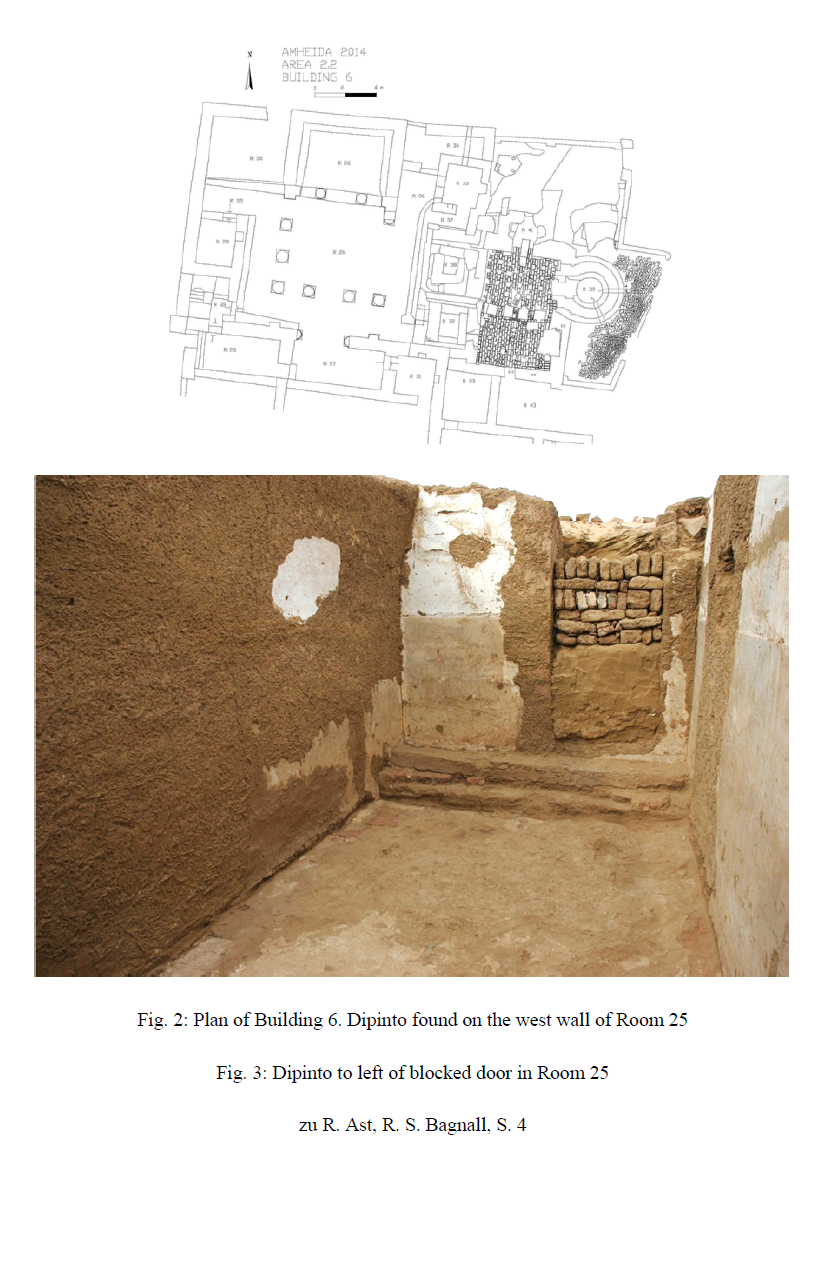

Inv. 14441. Area 2.2, Room 25, B6, FSU 49, FN 5, West Wall.

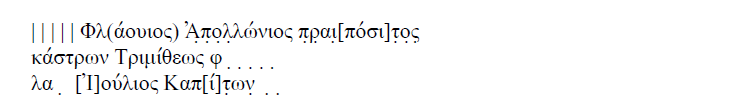

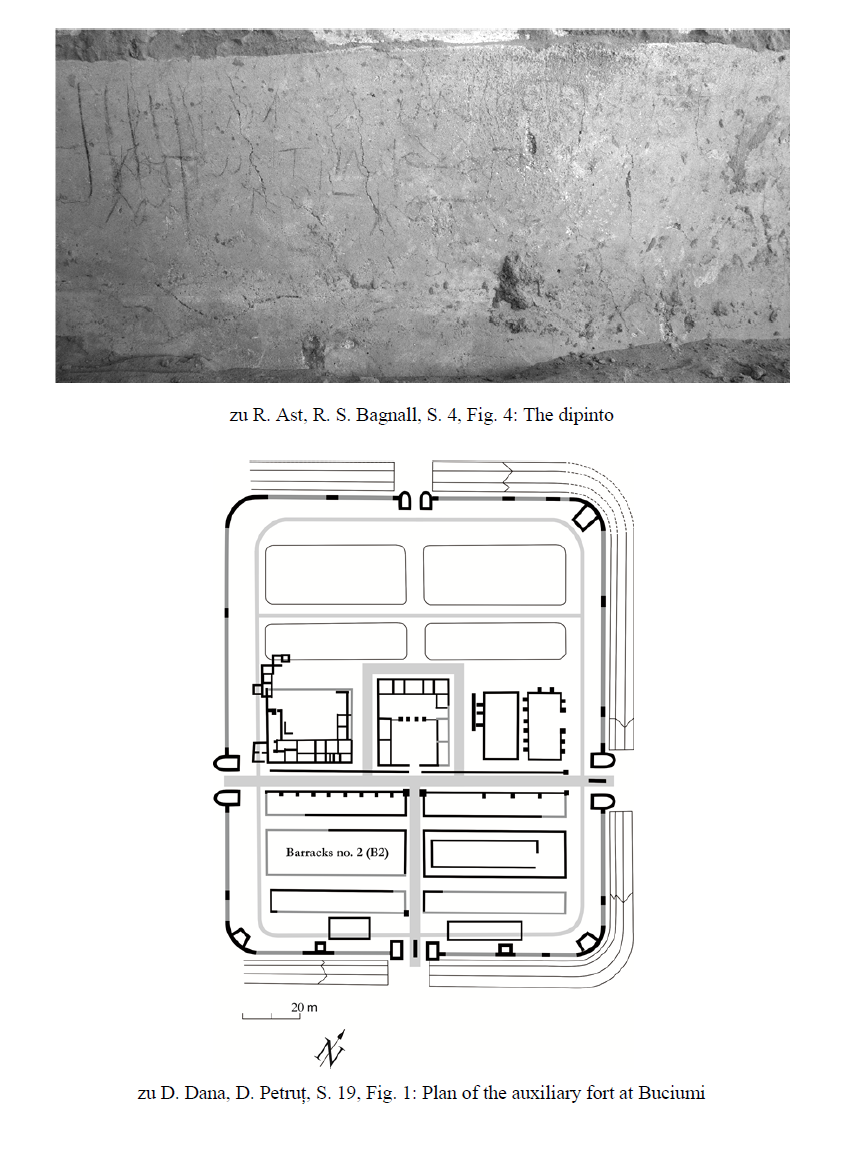

The 2011 excavation season was cut short by the Egyptian Revolution. During the few days spent in the field, loose sand was removed from Room 25 in Building 6, part of the renovated bathhouse, which represented the final phase of a large public bath located on the site and dating back to the 3rd century.[16] In the room a dipinto with a 3-line Greek text was discovered on the west wall next to a door and above two steps (pl. 2 fig. 2).[17] The top of the first line was written approximately 158 cm above floor level on smooth, gray hydraulic plaster, a few centimeters below a small decorative ledge dividing the gray from a polished white plaster. The dipinto and plaster were apparently covered over with mud plaster, perhaps when the walls were incorporated into Building 6. By the time of its discovery, the charcoal writing was already worn and very faint in places, especially on the right side of the text where the surface had developed gritty salt deposits. By the 2013 season the writing had nearly disappeared, and by 2014 it was entirely gone (pl. 2/3 fig. 3 and 4).

The surface covered by the text measures 14 cm high and ca. 65 cm wide. Indi- vidual letter sizes are exemplified by kappa in line 2, which measures 3.2 (h) × 2.5 (w) cm; tau in Τριμίθεως, which is 3 × 3 cm; and the first lambda in line 3, which is 4 (h) × 3.6 (w) cm. The dipinto begins with the name of what appears to be the prae- positus of the garrison, Flavius Apollonius. His nomen gentile dates the text to some- time after 325.[18] Several places have so far defied interpretation, especially the end of line 2 and the beginning of line 3.

“Flavius Apollonius, praepositus of the camp of Trimithis . . . Julius Capito. . . .”

1 The end of the line is very difficult to make out and the reading not entirely certain.

3 We suppose that the first letters are the end of a word or name beginning in line 2.

- - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -

Rodney Ast |

Roger S. Bagnall |

[1] P. Kucera, al-Qasr: the Roman Castrum of Dakhleh Oasis, in: R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli, C. A. Hope (eds.), The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, Oxford 2012, 305–316.

[2] Annual reports on the excavations at Amheida and a complete bibliography of publications of the excavations and the finds can be found at www.amheida.org.

[3] I. Gardner, Coptic Ostraka from Qasr al-Dakhleh, in: Bagnall et al., The Oasis Papers 6 (above fn. 1), 471–474.

[4] F. Colin, Baḥariya. I, Le fort romain de Qaret el-Toub I, Cairo 2012.

[5]5 This is available online at http://dlib.nyu.edu/awdl/isaw/amheida-i-otrim-1/.[6] Some of this material was made available in advance to Kucera, but it was not used in his article.

[7] Not. Dig. Or. 31.25, p. 64 Seeck; see also P.Erl.Diosp. 1.73–74n.

[8] A further ostracon, I 329 (see below), also mentions the annona in Mothis. The Notitia Dignitatum refers to a cohors scutata civium Romanorum, Mutheos (31.59, p. 65 Seeck) three entries after that to the ala at Trimithis; whether Mutheos is to be identified with Mothis is uncertain.

[9] See, e.g., O.Douch I 30.3, II 85.5, 88.5, 153 concave (side), 4.

[10] Cf. G. Wagner, Les oasis d’Égypte, Cairo 1987, 384.

[11] O.Douch I 13.6, IV 465.3, 473.4, V 553.5, 573.1, 637.

[12] F. Mitthof, Annona militaris. Die Heeresversorgung im spätantiken Ägypten, Florence 2001, 143–144.

[13] Kucera (above fn. 1), 313–314.

[14] For discussion of the office of actuarius, see comments on O.Trim. I 37 and Mitthof (above fn. 12), 152–156; on the possibility of a garrison at Mothis, cf. above, fn. 8.

[15] First attested in A.D. 280 (P.Oxy. IX 1191), the scriba is known to have served municipal councils (see, for example, P.Panop. 27.24 and 29.17; cf. also P.Erl.Diosp. 96n. and A. K. Bowman, The Town Councils of Roman Egypt, Toronto 1971, 39–41). Some evidence suggests that he was also involved in imperial service, including military affairs. A good example of this is P.Lond. VI 1914.19 (May 23, 335; Heracleopolite or Cynopolite Nome), where a praepositus of a camp (παρεμβολή) at Alexandria and a scriba join in the common cause of expelling Meletian monks from the camp. H.I. Bell notes in the ed. pr. that the scriba was “no doubt a military scribe, on the staff of the praepositus.” Given the prevalence of military rather than civil offices in the Trimithis ostraka, we tend to the view that the scribae were probably also military officials.

[16] P. Davoli, A New Public Bath in Trimithis (Amheida, Dakhla Oasis), in: B. Redon (ed.), L e bain collectif en Égypte 2. Découvertes récentes et synthèses. Proceedings of the International Conference, Cairo October 26, 2010, Cairo (in press).

[17] For a detailed description of the wall on which the dipinto was found, see http://www. amheida.com/db/unit/A-2.2-F49 (login as guest required).

[18] J. G. Keenan, The Names Flavius and Aurelius as Status Designations in Later Roman

Egypt , ZPE 11 (1973) 33–63.