ADNOTATIONES EPIGRAPHICAE V

<Adn. Tyche>

Kom Aushim inv. no. 521 is a large limestone block that preserves the partial remains of a dedicatory inscription to the god Soxis and was published by Guy Wagner and S. A. A. El-Nassery in 1975[1]. While recently examining this inscription in the Kom Aushim magazine I compared the transcription provided by Wagner and El-Nassery with the actual inscription and noticed that there was an error in the published edition of this text that has never been corrected[2]. It occurs in the first extant line of the transcription where there is a misreading of the first word that consequently changes the titulature, which is lost, but preceded the first line of extant text. The mutually agreed reading for the beginning of the first line of text is λαδελφω. Wagner and El-Nassery then read Iota which consequently lead them to the following reconstruction: [βασιλεῖ Πτολεμαίωι θεῶι Φιλοπάτορι καὶ Φι]|λαδέλφωι … . As noted in the article they settle on this reconstruction primarily because of the paleography of the text, which suggests a late Ptolemaic date, and because there are numerous inscriptional references to Ptolemy XII Auletes Philopater Philadelphos[3]. However, the reconstructed form of the titulature they provide is a little odd, not least because they cannot provide a compelling contextual parallel, but also because the reconstruction is unusual in a dedicatory inscription of the type we are dealing with here. Most often dedicatory inscriptions of that type begin with the preposition ὑπέρ so that the following titulature is governed by the genitive case[4].

Based on an examination of the actual inscription it is evident that they have misread the first word, which changes the preceding titulature, although it does not change the reference to Ptolemy XII Auletes. What follows λαδελφω is not Iota but a Nu; therefore the reading of the first word is λαδελφων. Having personally examined the inscription, the reading is definitely a Nu even though the top is partially effaced [5]. Searching for this letter combination in inscriptions reveals that it occurs about a dozen times and in every case represents the final part of a titulary formula for Ptolemy XII Auletes Philopater Philadelphos. The most common formula and the one that appears most often in dedicatory contexts is: ὑπὲρ βασιλέως Πτολεμαίου καὶ βασιλίσσης Κλεοπάτρας τῆς καὶ Τρυφαίνης θεῶν Φιλοπατόρ̣ων καὶ Φιλαδέλφων [6]. Turning to the papyri, a search for λαδελφων produces a dozen attestations and in every instance but one, which is a spelling error, refers to Ptolemy XII Auletes[7]. Interestingly, three papyri date to “year 9,” the same year mentioned on l. 4 of the extant text of the inscription, and contain the same titulature just cited [8].

Lincoln H. BLUMELL

A Latin public inscription from the conventus centre of Synnada (Phrygia) is printed by Peter Thonemann in the concluding volume of the MAMA series thus (MAMA XI 178):

As the first editor noted, ‘in line 2, we presumably have the genitive [- - provin]ciae’. Further tentative restorations seem possible, determining the nature of this text as a ‘career inscription’. If the offices held were listed in ascending order, we would expect a fragment of a name in l. 1 (arguably the ending of a gentilicium in the dative and the beginning of a cognomen), followed by [quaestori or q. pro pr. provin]ciae in l. 2 and then [praetori] urb[ano] in l. 3. Alternatively, in descending order, the name would be followed by a mention of a consulship and proconsulship [provin]ciae [e.g. Asiae] and then of a curatorship [alvei et riparum Tiberis et cloacarum] urb[is]. The title in l. 4 clearly includes the adjective consularis, which precludes mention of the honorand’s praetorship in the preceding line if his offices are listed in descending order. Speculating on the exact office-title with that element is obviously insecure given the variety of both Roman and provincial possibilities from the late second century AD onwards; assuming the dative case here, [consul]ari S[ardiniae] or S[iciliae] might be one possible solution.[9]

Palaeographic features of the inscription would not preclude even a mention of a consularis sexfascalis or of another fourth-century AD office, but ‘an extremely fine monumental script, with unusually wide interlinear spaces’ (Thonemann) makes an honorific inscription for a proconsul of Asia whose career included an earlier governorship elsewhere somewhat more likely. The remains would not, however, fit the known career of the only known proconsul of Asia whose cognomen begins with the letters TA, the historian Cornelius Tacitus.

In the report of the excavation of the ‘Double Table’ at Anchialos Michalis Tiverios records a vase with a graffito of the name Βόρυς. He considers the name Scythian, drawing parallels with the place-names Βορυσθένης and Βορυσθενίς.[10] The name is in fact very well attested at Sinope, particularly on Sinopean amphora stamps, and does not otherwise appear elsewhere, certainly not at Olbia-Borysthenes itself, while Βορυσθένης and Βορυσθενίς are not in fact attested as personal names.[11] The graffito should be added to the record of Sinopeans abroad.[12]

An inscription from Chios, published by Dimitrios Evangelidis in 1927 and not much noticed since, might provide interesting evidence on an aspect of grants of Roman citizenship to provincials in the second century AD.[13] One side of the stone contains honours to Aur(elius) Neikandros from the council and people of Chios, presumably post-dating the universal grant of citizenship in AD 212; the other, in a different hand, but palaeographically conceivably from the same or a slightly earlier period, has honours from the gerousia to Lucius Ulpius Glykon of the tribe Sergia: ἡ γε<ρ>ουσία ἐτείμησεν | [- - -]ον Λούκιον Οὔλπιον | [- - -] υἱὸν Σεργία Γλύκωνα (ll. 1–3).

Two considerations taken together speak against the natural suggestion that the family of Ulpius Glykon owed its citizenship directly to Trajan: the uncommon combination of the imperial gentilicium with the praenomen Lucius and Hadrian’s tribe Sergia instead of Trajan’s Papiria. [14]

A better candidate for the sponsor of their citizenship may be proposed. It has been suggested by J. H. Oliver and A. R. Birley that Ulpius Marcellus, attested in a letter of Commodus to Aphrodisias as the proconsul of Asia and imperial amicus in AD 189, is the same as L. Ulpius Marcellus, governor of Britain in ca. AD 177–185 and of Lower Pannonia before that.[15] Birley identifies a number of Ulpii Marcelli in the province of Asia whom he views as possible relatives of the proconsul, almost certainly showing an established network of local influence. One of them, Ulpius Tatianus Marcellus (IGRR III 299) comes from Pisidian Antioch, a city in the Sergia. [16] It seems better to view our Lucius Ulpius Glykon (and perhaps even some of Asian Ulpii Marcelli) as owing his citizenship to the good services of the proconsul than to derive his citizenship from Trajan himself. [17] If this suggestion is correct, the text would provide evidence for proconsuls still being involved in granting citizenship and passing on their nomina to enfranchised provincials at the end of the Antonine period.

Georgy KANTOR

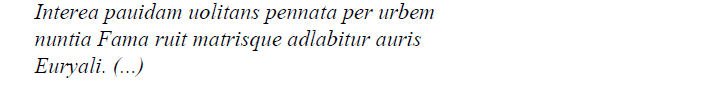

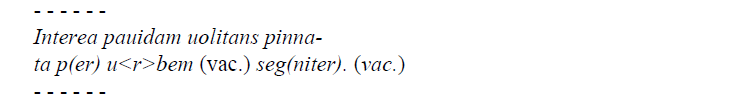

T.Vindol. II 118 (written on the obverse of letter draft T.Vindol. II 331) reads as follows:[18]

This has commonly been thought of as a pupil’s exercise of sorts,[19] copying the beginning of a famous passage from the ninth book of Vergil’s Aeneid, namely Verg. Aen. 9,473–475, at which the rumour of her son’s death reaches Euryalus’ mother:[20]

“Meanwhile Rumour, the winged messenger, rushes ahead, fluttering across the trembling town, and reaches the ears of Euryalus’ mother.”

Accordingly, the text of the tablet has been restored and interpreted by the editors (and others)[21] as follows:[22]

‘Meanwhile (scil. Rumour), the winged (scil. messenger, rushes ahead), fluttering across the trembling town. . .’ – ‘Slack!’

The ‘teacher’ (if this is indeed the underlying scenario that resulted in the addition of what seems to say seg(niter), in a different hand) [23] may well have taken the writing on this tablet in the same way as its modern interpreters.

Another interpretation is possible, however — an interpretation that accounts for the spellings of line 2 without the assumption of any abbreviations or mistakes (which, incidentally, are absent from the first line, as pinnata is hardly more than an orthographical variant of pennata in Classical Latin). The alternative interpretation that one ought to consider is this:

‘Meanwhile, the winged, fluttering, a trembling pubes . . .’ – ‘Slack!’

Pauidam ... pubem , ‘trembling pubes’ (vel sim.),[24] could thus have advanced to become the object of what follows in the Vergilian passage, nuntia Fama ruit (‘messenger Rumour casts’) — but there is, of course, no urgent need to supply ruit at this stage so as for this obscenity to develop its force.

Finally, if the ‘teacher’ understood the ‘pupil’s’ obscene variation of Vergil’s line, of course, one may wish to take his comment seg(niter) as ‘lame’ or ‘dumb’ rather than ‘slack’.[25]

Peter KRUSCHWITZ

The edition of CIL VI 5953[26], a metrical inscription, has been lately corrected by Matteo Massaro [27]. This correction affects the word iter in the third line, which must be read as ter. Still, some observations about the ordinatio of this third line can be pointed out in order to complement Massaro’s study.

The attention must be called to a virgula between piissimo and ter in the third line of the inscription (see fig. 1). The connection between this virgula and ter was misunderstood by the scholars of the Settecento, who read her(es) by interpreting the sign as П or H,[28]. Since this term was not reasonably translatable, it was finally corrected to iter[29], a correction that no one until Massaro has questioned. Neither her nor iter are possible, given that the stone clearly contains the word ter.

The stroke on CIL VI 5953 is related to the ordinatio, the study of which in the Latin verse inscriptions has increased strikingly in the last decade[30]. A good knowledge of this subject may be useful to recognise new carmina in fragmentary inscriptions, or even in inscriptions previously published as prose, but also to reconsider earlier editions as in the case of CIL VI 5953.

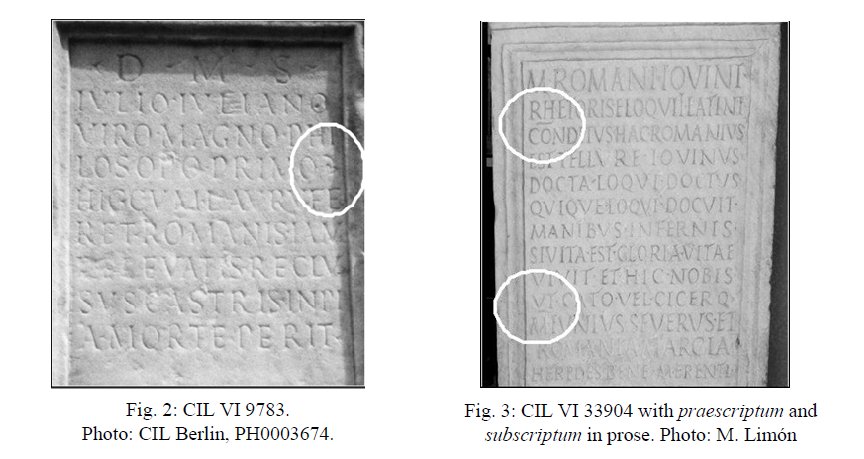

Regarding CIL VI 5953, the carmen is preceded by a prose praescriptum finishing with piissimo. In particular, the virgula is placed between piissimo and ter with the only purpose of separating prose from verse. It is important to highlight this sign which was ignored until Massaro’s paper[31]. The custom of marking the bound between prose and verse by a graphic sign is well-documented in Latin verse inscriptions, whether the prose precedes or follows the verse (see figs. 2–3). Graphic signs are especially used when there is no difference between the lettering size of the text in prose and of the text in verse [32], as in the case of CIL VI 5953. Thus, the reader should be able to distinguish both parts almost without difficulty. Although the use of a virgula in this use is a unique case within the carmina of Rome[33], we have documented other signs with the same function in inscriptions from both Rome and Spain [34].

The signs of punctuation, like this virgula separating different parts of the text, have been neglected and therefore often ignored. This is the main reason for the confusion of this virgula with the letter I, and clearly the starting point of this misreading held for quite a long time. It is reasonable that the first editors opted for the lectio facilior, and that they did not hesitate in reading (or reconstructing) the word iter, which, in addition, was perfectly appropriate in the context of the inscription. This case must be taken as a clear example of the importance of bearing in mind the ordinatio when editing Latin verse inscriptions.

María LIMÓN BELÉN

Die Inschrift AE 1937, 101 = LIA 165 aus Scampa (Elbasan, Albanien) überliefert uns die Laufbahn des M. Sabidius Maximus, der zunächst in der legio V Macedonica vom miles zum centurio aufstieg und danach von Hadrian und Antoninus Pius mehrfach befördert und in eine andere Legion versetzt wurde. Zu den unklaren Angaben am Schluß der Inschrift zählt jener Passus am Übergang von Z. 14 zu 15, in welchem zunächst möglicherweise das Sterbealter des Maximus und dann mit Sicherheit die Anzahl seiner Stipendien angeführt werden. Von den bisherigen Bearbeitern wurde dieser Abschnitt wie folgt gelesen bzw. wiederhergestellt:

A. Betz, JOEAI (Beibl.) 30 (1937) 101–108:

[v(ixit) a(nnos) LXX? mil(itavit) st(ipendia)] / |(centurioni)ka ( l. centurionica) XX continua XL

AE 1937, 101:

v(ixit) [a(nnos) . . mil(itavit) st(ipendia)] / |(centurio-) KA XX continua XL

ILAlb 88:

[v(ixit) a(nnos) LXX? mil(itavit) st(ipendia)] / |(centurioni)ka ( l. centurionica) XX continua XL

IDRE 364:

v(ixit) [a(nnos) …, st(ipendia)] / |(centurioni)ka ( l. centurionica) XX, continua XL

CIA 153:

[v(ixit) a(nnos) LXX? mil(itavit) st(ipendia)] / |(centurioni) (centuriae) Ka(esonii) XX continua XL

É. Deniaux, in: M. Silvestrini (Hg.), Le tribù romane, Bari 2010, 67–68:

[v(ixit) a(nnos) LXX? mil(itavit) st(ipendia)] / |(centurioni) (centuriae) ka(ndidato) XX continua XL

LIA 165:

[---] / |(centurioni?) I’ A’ XX continua XL

Es besteht somit Konsens, daß das verlorene Bezugswort für continua und die beiden Ziffern XX und XL mit stipendia zu identifizieren ist. Was das zugehörige Verb betrifft, so wären neben dem bislang angenommenen militavit auch andere Formulierungen wie accepit denkbar (s. unten AE 1990, 896). Fest steht ferner, daß am Anfang von Z. 14 die im militärischen Milieu übliche Sigle für das Wortfeld centurio/ centuria zu finden ist.

Hingegen ist die Deutung der Buchstaben KA noch immer unklar[35]. Als Alternative zu den bisherigen Vorschlägen möchte ich auf die Möglichkeit hinweisen, daß sich nach dem Vorbild von AE 1990, 896 (…stipendia ac/cepit caligata XVI evo/cativa VII centurioni/ca IIII militavit annis XXVII …) hinter der Verbindung KA auch das Wort kaligata (l. caligata) verbergen könnte. Die Verwendung von K für C in Wörtern, die auf CA- anlauten, ist in kaiserzeitlichen Inschriften ein bekanntes Phänomen — man denke nur an karus/karissimus, kastra oder kandidatus —, und diese Schreibweise wurde sogar von einigen Grammatikern des Zeitalters als die korrekte Form erachtet[36]. Im Übrigen hat ja schon Betz eine solche C-K-Vertauschung (centurionika) postuliert, die freilich im Binnenlaut eher ungewöhnlich wäre. Der neue Deutungsvorschlag für die Stelle lautet demnach wie folgt:

[v(ixit) a(nnos) . . . (?) mil(itavit ) vel acc(epit ) stip(endia)] / (centurionica) ka(ligata) (l. caligata) XX continua XL

Ob die verkürzte Ausdrucksweise vom Verfasser so intendiert war oder ob er die Ziffer XX nach (centurionica) versehentlich ausgelassen hat, bliebe bei einer solchen Deutung ungewiß. Der Sinn des Passus schiene in jedem Fall klar: Maximus hatte 20 Jahre als centurio und (zuvor) 20 Jahre als gregarius in den Mannschaftsdienstgraden gedient[37], was eine Gesamtdauer seines Militärdienstes von 40 Jahren ohne Unterbrechung ergab.

Fritz MITTHOF

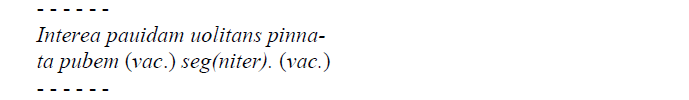

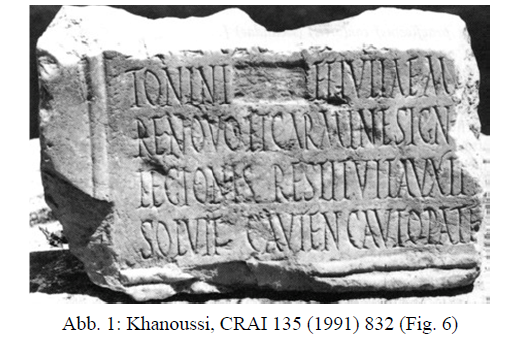

Die unter der Nummer AE 1992, 1823 aufgenommene Inschrift bietet die Transkription einer fragmentarischen Weihinschrift an Mithras aus Simitthus (Africa proconsularis). Die Kaisertitulatur in den beiden ersten Zeilen ist nur noch fragmentarisch am Stein zu erkennen. Lediglich der Name [An]|tonini ist sicher zu lesen. Danach folgt eine Rasur von etwa 3–5 Buchstaben und die Nennung einer Iuliae Ma[---.

In der Erstedition von Mustapha Khanoussi[38], der die Inschrift vorerst flüchtig bearbeitet und einen ausführlichen Kommentar angekündigt hat, wird der gesamte Text folgendermaßen wiedergegeben[39]:

Khanoussi identifiziert den genannten [AN]TONINI mit Kaiser Elagabal (218–222 n. Chr.), vermutlich zum einen aufgrund der Rasur und zum anderen aufgrund seiner Annahme, dass der unvollständige Name IVLIAE MA auf Elagabals Großmutter Iulia Maesa zu beziehen sei. Zwei Jahre später wurde dieselbe Inschrift in Friedrich Rakob (Hrsg.), Simitthus I. Die Steinbrüche und die antike Stadt, Mainz am Rhein 1993 aufgenommen. In dem darin enthaltenen Beitrag von Khanoussi (S. 66–67) findet sich die idente Transkription sowie der gleiche Kommentar wie in der editio princeps unter dem Titel „Mention de la légion sous Elagabal“ wieder, abermals mit der Ankündigung eines detaillierten Kommentars (S. 67, Anm. 133).

In AE 1992, 1823 wurde die Interpretation von Khanoussi einschließlich der Ergänzung der Kaisertitulatur des Elagabal und des Namens der Iulia Maesa übernommen:

![]()

Bei genauerer Betrachtung des Steines anhand des Fotos lassen sich meines Erachtens in Z. 1 (Mitte) recht deutlich Reste der Buchstaben CAE und gegen Ende der Zeile möglicherweise noch die Serifen der Buchstabensequenz ELI(?) (oberhalb von VLI) erkennen, die für die Rekonstruktion der Kaisertitulatur hilfreich sind. Die in AE vorgenommene Ergänzung der Kaisertitulatur basiert vor allem auf der Annahme, dass rechts kaum Textverlust vorliegt. Nach dem Cognomen [An]tonini folgten für gewöhnlich noch die Epitheta P(ius) F(elix) und der Augustus-Titel. Eine Rasur dieser einzelnen Elemente stellt aber eine eher unübliche Maßnahme dar. Die damnatio memoriae, die im März 222 n. Chr. offiziell über Elagabal verhängt wurde, findet in der epigraphischen Evidenz zwar deutlich ihren Niederschlag, am häufigsten wurde dabei aber eben gerade das Cognomen Antoninus selbst oder sogar, wie in 21 Inschriften belegt, die gesamte kaiserliche Formel getilgt[40]. Daher stellt sich die Frage, ob [An]tonini nicht vielmehr Teil der Filiation war[41]. Die partielle Tilgung der Filiationsangabe Divi Magni Antonini (Pii) filius, insbesondere aber auch nur der Angabe filius, lässt sich bislang in 8 Inschriften nachweisen[42]. In Anbetracht der Größe der Lücke könnte ursprünglich PII F oder FILII/FILIO eingemeißelt gewesen sein. Ob in der kaum mehr erhaltenen Z. 1 noch weitere Tilgungen vorgenommen wurden, lässt sich nicht mehr eruieren.

Die Filiationsangabe Divi Magni Antonini (Pii) filius führte jedoch nicht nur Elagabal, sondern auch sein Adoptivsohn Severus Alexander (13. März 222–Febr./März 235)[43], zu dessen Titulatur die in Z. 1 noch erkennbaren Spuren von C̣ạẹ[s(aris)] und [Aur]ẹḷị(?) genauso passen würden. Die partielle Tilgung von Teilen der Filiationsangabe ist ebenfalls bei Severus Alexander dokumentiert[44]. Damit wäre auch die Ergänzung Ma[esae ---] in Z. 2 keineswegs sicher. IVLIAE MA[- - -] könnte ebenso zu Iuliae Ma[maeae ---], dem Namen der Mutter des Severus Alexander, ergänzt werden, auf den möglicherweise noch weitere Titulaturelemente, zumindest aber der Augusta-Titel folgten[45]. In jedem Fall scheint es eine Besonderheit der Inschrift zu sein, dass sie eine (zumindest partielle) Tilgung lediglich bei der Titulatur des Kaisers, nicht aber bei seiner weiblichen Begleiterin — Maesa oder Mamaea — dokumentiert.

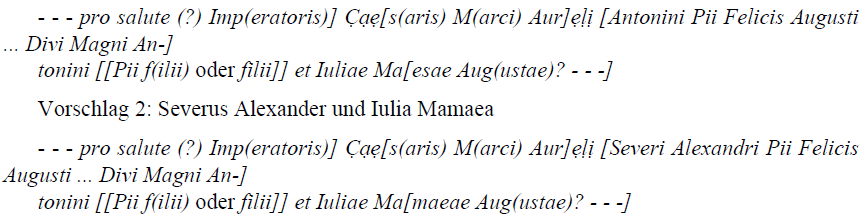

So muss letztlich offen bleiben, ob Elagabal oder sein Nachfolger Severus Alexander in dieser Inschrift genannt waren, zumal auch die hier genannte Augusta nicht sicher identifiziert werden kann. In Anbetracht dessen, dass in der Inschrift (wahrscheinlich) eine partielle Tilgung der Filiationsangabe vorliegt, die das letzte Element der Kaisertitulatur bildete, ist davon auszugehen, dass die erhaltene Länge des Inschriftenfragmentes etwa nur ein Drittel der gesamten Tafel ausmacht[46]. Weitere Überlegungen zu den Titulaturelementen des genannten Kaisers bleiben Spekulation. Dennoch sollen abschließend zwei Ergänzungsvorschläge, die auf dem dargelegten Interpretationsansatz aufbauen, geboten werden:

Vorschlag 1: Elagabal und Iulia Maesa

Kerstin SÄNGER-BÖHM

[1] Une nouvelle dédicace au grand dieu Soxis , ZPE 19 (1975) 139–142.

[2] Subsequent treatments of this inscription have simply reproduced the transcription given by Wagner and El-Nassery: L. u. J. Robert,Bulletin épigraphique, REG 89 (1976) 579 (no. 763); J. Bingen, Sammelbuch Griechischer Urkunden aus Ägypten. Zwölfter Band [Review], CE 51 (1976) 218; I.Fayum II pp. 136–137; I.Fayum III 138 pl. 41; cf. A. Łukaszewicz, A Petition from Priests to Hadrian, in: Pap.Congr. XVI (1981) 360. This inscription is not treated in the SEG.

[3] Wagner, El-Nassery, Une nouvelle dédicace (n. 1 above) 140–141. The reference to “S.B. 1105” is incorrect, the intended reference is to SB I 1104 which reads: βασιλεῖ Πτολεμαίωι καὶ Ἀρσινόηι Φιλαδέλφωι Πτολεμαῖος φρούραρχος καὶ οἱ ὑπ’ αὐτὸν στρατιῶται.

[4] For example, in I.Fayum II 115 (= SB III 6309; 67 BC; Theadelphia), a fully intact inscription from the reign of Ptolemy XII Auletes whose content is remarkably similar to the present inscription, even bearing a number of specific textual parallels to the dedication itself, reads as follows: ὑπὲρ βασιλέως Πτολε|μαίου θεοῦ Φιλοπάτορ|ος καὶ Φιλαδέλφου Πετο|σῖρις Ἡρακλήους καὶ ἡ γυνὴ καὶ | τὰ τέκνα τὸ πρόπυλον Ἥρωνι | θεῶι μεγάλωι μεγάλωι· | (ἔτους) ιεʹ, Θῶυθ ιθʹ. Despite the many parallels I.Fayum II 115 (= SB III 6309) is never cited in Wagner and El-Nassery’s analysis.

[5] Furthermore, the reading of Iota leaves an unusually large gap in the text before Pi.

[6] I.Hermoupolis Magna 5.1–2 (= É. Bernand, Inscriptions grecques d’Hermoupolis Magna et de la nécropole, Le Caire 1999 = SB I 4206; 80/79 BC); I.Hermoupolis Magna 6.1–2 (= SB V 8066; Jan. 25, 78 BC); I.Fayum I 9.1–4 (= SB I 623 = SEG 1728; 80/79, 69–7 BC); I.Fayum I 10.1–6 (80–68 BC; Arsinoe); I.Fayum III 145.1–2 (= SB I 5801; 90–68 BC); OGIS 182.1–2. (= SB I 4206; 80–69 BC, Hermopolis); I.Cairo Mus. 25,9296 (80–69 BC, Hermopolis); SB I 4963.1–3 (51–47 BC); SB V 8066.1–2 (78 BC; Hermopolis). Another attested formula that incorporates λαδελφων can be found in OGIS 741.1–4 (= SB V 8933; 52 BC): ὑπὲρ βασιλέως Πτολεμαίου | θεοῦ Νέου Διονύσου, καὶ τῶν | τέκνων αὐτοῦ, θεῶν Νέων Φιλ|αδέλφων. But this formula can be ruled out for the present inscription since it does not begin to be used until later in Ptolemy XII Auletes’ rule, after 69 BC, well beyond the “year 9” (= 73/72 BC) mentioned in l. 4 of the extant text of the present inscription: see A. Bernand, Les inscriptions grecques de Philae. Vol. I: Époque ptolemaïque, Paris, 1969, 300–301.

[7] The single instance where λαδελφων does not refer to Ptolemy XII Auletes is in BGU IV 1049.17 (342 AD; Ptolemais Euergetis), but the intended spelling here is Φιλάδελφον.

[8] O.Joach. 7.1–4 (= SB III 6033; Dec. 5, 73 BC; Ombos): ἔτους θ, Ἁθὺρ κζ, ἐπὶ β̣[ασι]|λέως Πτολεμαίου καὶ βασιλ(ίσσης) | Κλεοπάτρας τῆς καὶ Τρυφα(ίνης) | θεῶν Φιλοπα(τόρων) Φιλ(α)δέλ(φων); P.Oxy. XIV 1628.1–2 (Oct. 24, 73 BC; Oxyrhynchus): [βασι]λ̣ευόντων Πτολεμαίου καὶ Κλεοπάτρας [τῆς καὶ] | [Τ]ρυφα[ί]νης θεῶν Φιλοπ[α]τ̣ό̣[ρ]ω̣ν̣ [Φ]ι̣λ̣αδέλφων ἔ[το]υ̣[ς θ] (year 9 is mentioned in l. 25 of this papyrus); P.Oxy. XLIX 3482.1–2 (Oct. 8, 73 BC; Oxyrhynchus): βασιλευόντων Πτολεμ[α]ί[ου καὶ Κ]λ̣εοπάτρας τῆς καὶ Τρυφαίνης θεῶν Φιλοπατόρων Φιλαδέλφων, ἔτους | ἐνάτου; cf. SB VI 9092.1–3 (Oct. 10 – Nov. 8, 73 BC; Oxyrhynchus): [βασιλευόντ]ω̣ν Πτολεμαίου καὶ [Κλεοπάτρας τῆς καὶ] | [Τρυφαίνης θε]ῶν Φιλοπατόρω[ν Φιλαδέλφων] | [ἔτους θ τὰ δʼ].

[9] R. Paribeni, Consularis, in: Diz. Epigr. II (1910) 864–868, still provides a useful entry point. Note also Gaius Hasta, consularis trium Daciarum under Commodus (AE 1981, 801), and the more obscure consularis prov. Brit. mentioned in RIB I 1205. For Italian posts, W. Eck, Die staatliche Organisation Italiens in der hohen Kaiserzeit, München 1979, 247–248. A mention of Pompeius Falco (cos. suff. AD 108, PIR2 P 602) as leg. pr. pr. [pr]ovinciae Iudaeae consularis in ILS 1036, ll. 3/4, is almost certainly a mistaken expansion of cos. by a local stonecutter, as seen already by Dessau.

[10] Μ. Tiverios, Οι ανασκαφικές έρευνες στη διπλή τράπεζα της Αγχιάλου κατά το 1993, ΑΕΜΘ 7 (1993) 244 and 250 ph. 5 (whence SEG XLVI 724 and LGPN IV s.v.). Cf. M. B. Hatzopoulos, BE (1997) no. 387 (‘l’anthroponyme ... Βόρυς, qu’il considère non hellénique’).

[11] To references in LGPN VA s.v. add now SEG LVIII 746.30; 761.11; LIX 776. The only example of a Borysthenes in LGPN thus far (IIIA s.v.) comes from a 2nd-cent. AD Latin inscription of Puteoli (T. Aelius Borysthenes, CIL X 2013).

[12] For Synopeans abroad, see now A. Avram, Prosopographia Ponti Euxini externa, Leuven 2013, 257–290 nos. 2813–3056 (not recording our case).

[13] D. Evangelidis, Επιγραφαί εκ Χίου, ΑΔ 11 (1927–1928) Chron. 27 no. 8 (ph. of the squeeze); not noticed in the catalogue of B. Holtheide, Römische Bürgerrechtspolitik und römische Neubürger in der Provinz Asia, Freiburg 1983. I am grateful to Charles Crowther, who is preparing a new edition of the stone for the Chios fascicle of IG XII, for the discussion of my suggestion and his comments on the palaeographic features; his edition will contain new readings, which do not affect the argument here. I print Evangelidis’ text.

[14] For the evidence on the tribal affiliations of the Ulpii, admittedly less clear-cut than standard accounts might suggest, see now G. Forni, Le tribù Romane I. Tribules, vol. 4, Roma 2012, 1187–1191 nos. 5–37. There are only three Ulpii from the Sergia, including our case from Chios (ibid., 1189 no. 19). The tribal affiliation of one, M. Ulpius Iaraios from Palmyra (AE 1947, 171 = ibid., 1189 no. 22), might, as Henri A. Seyrig suggested, be explained by Hadrian’s grant of municipal status to his hometown and so not come from Trajan either. For Publius Aelius, son of P. Aelius, Lysimachos from the tribe Sergia (whose father clearly had been granted his citizenship by Hadrian), the only other attested tribulis of Sergia on Chios, cf. IGRR IV 951. For a Lucius Ulpius being father of a Marcus Ulpius, see CIL VI 29252, the only such example to my knowledge.

[15] IAph2007 no. 8.35 l. 13: τῷ φίλῳ μου Οὐλ[πί]ῳ Μαρκ̣[έλλῳ]. Cf. J. H. Oliver, Greek Constitutions no. 211 ad loc.; A. R. Birley, The Roman Government of Britain, Oxford 2005, 170.

[16] For the tribal affiliation of Pisidian Antioch, W. Kubitschek, Imperium Romanum tributim discriptum, Wien 1892, 243.

[17] Compare especially H. Box, Roman Citizenship in Laconia, JRS 21 (1931) 204 for the appearance of the nomen Claudius at Sparta in the second century AD, and 209 for the Spartan Memmii, owing their citizen-status to a proconsul. Note also the eye doctor L. Ulpius Deciminus attested on a collyrium-stamp from Colchester (RIB II 2446.8); A. R. Birley, The Roman Inscriptions of Britain; vol. II: Instrumentum domesticum, fasc. 1–4, hg. v. S. S. Frere et al., Gloucester 1993 (review), JRS 83 (1993) 238 adduces him as an example that ‘Romanized Celts liked to ring the changes with praenomina’, but a grant of citizenship through the governor’s agency may be an explanation.

[18]

In addition to the edition and commentary in T. Vindol., see now M. C. Scappaticcio, Papyri Vergilianae: l'apporto della Papirologia alla Storia della Tradizione virgiliana (I-VI d.C.), Liège 2013, 141-142 no. 23. An image

is available at http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk/

exhibition/images/118.jpg.

[19] Cf. A. K. Bowman, J. D. Thomas, The Vindolanda Writing Tablets (Tabulae Vindolandenses II), London 1994, 65–67 (also available at http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk), a view taken by many since (cf. e. g. S. MacCormack,The Shadows of Poetry. Vergil in the Mind of Augustine, Berkeley 1998, 3 nt. 8, J. M. Ziolkowski, M. C. J. Putnam (ed.),The Vergilian Tradition. The First Fifteen Hundred Years, New Haven, London 2008, 44–45, or J. Wintjes,Keep the Women out of the Camp!: Women and Military Institutions in the Classical World, in: B. C. Hacker, M. Vining (ed.), A Companion to Women’s Military History, Leiden 2012, 17–59, esp. 17–18).

[20] On Vergil at Vindolanda see recently M. C. Scappaticcio, Virgilio, allievi e maestri a Vindolanda: per un’edizione di nuovi documenti dal forte britannico, ZPE 169 (2009) 59–70 (esp. 60–61 on the present tablet).

[21] In addition to the material assembled above n. 19, see e. g. A. K. Bowman, Life and Letters on the Roman Frontier. Vindolanda and Its People, London 32003, 11 and 88–89.

[22] Scappaticcio, Virgilio (above n. 20) suggests that the P in line 2, due to its graphic representation, is in fact to be understood asp(rae). This remains unconvincing, as (i) the form of the P (which occurs three times in the tablet — here, in pauidam, and in pinna|ta) is in flux and (ii) the shape of line 2 relatively closely resembles that of the P in pauidam.

[23] H. D. Jocelyn argued that, due to the consonantic cluster –gn–, the adverb segniter could not possibly be abbreviated seg. (on which see Scappaticcio, Virgilio [above n. 19] 61 with n. 13). This is, of course, as apodictic as it is indemonstrable. In fact, even a most superficial search in the manfredclauss.com database of Latin inscriptions yields numerous instances in the Latin inscriptions for e. g. forms and derivatives (including compounds) of cognoscere written as *-cog(n- - -).

[24] For pubes as a sexual term (referring to the pubic area more generally [cf. Auson. epigr. 58,6 Kay: tergo femina, pube vir es], pubic hair, or in fact the testicle) cf. J. N. Adams, Latin Sexual Vocabulary, London 1982, 68–69, 224 and 228.

[25] This would appear to be a more natural understanding, in keeping with the spectrum of meaning of Latin segnis –e, anyway.

[26] Preserved in the Palazzo Nuovo of the Capitoline Museum, fixed in the wall of the commonly named Sala delle colombe, inv. NCE 1941.

[27] Un “iter” di fantasia. Revisione e commento di CIL VI 5953 / CLE 1068 , ZPE 187 (2013) 164–172.

[28] For instance, F. Ficoroni, Le maschere sceniche e le figure comiche d. antichi Romani descritte brevemente, Roma 1736, 113; J. Russell,Letters from a Young Painter abroad to His Friends in England, London 21750, 128; P. Burmann, Anthologia veterum latinorum epigrammatum et poematum sive catalecta poetarum latinorum, II, Amsterdam 1773, nº 27.

[29] L. A. Muratori, Novus Thesaurus veterum inscriptionum, III, Milan 1740, MCDXCXIX, 10; F. E. Guasco Musei Capitolini antiquae inscriptiones, vol. III, Roma 1775, 528; Henzen, CIL VI 5953 (inde Bücheler, CLE 1068).

[30] It was first developed by J. del Hoyo, La ordinatio en los CLE Hispaniae, in: J. del Hoyo, J. Gómez Pallarès (ed.), Asta ac Pellege, 50 años de la publicación de Inscripciones Hispanas en Verso de S. Mariner, Madrid 2002, 143–162. Other studies on the same issue are: J. Gómez Pallarès, Carmina Latina Epigraphica de la Hispania republicana: un análisis desde la ordinatio, in: P. Kruschwitz (ed.), Die metrischen Inschriften der römischen Republik, Berlin, New York 2007, 223–240; M. Limón Belén, La compaginación de las inscripciones latinas en verso. Roma e Hispania, Roma 2014.

[31] Massaro, Un “iter” (above n. 27) 165 only remarks that “la barra obliqua abbastanza vistosa, che sostituisce l’interpunto ordinario tra piissimo e ter, non può che avere la funzione di segnalare graficamente la divisione tra le due parti”.

[32] Differentiating both parts by inscribing the prose with a bigger lettering size is quite frequent; see del Hoyo, La ordinatio (above n. 30) 158–159.

[33] Virgulae are also found in the carmina epigraphica to separate verses.

[34] Some other examples from Rome are CLE 685 and 1342 (with a hedera); CLE 105 and 757 (with a horizontal line); CLE 1064 and 1150 (with a blank space); from Hispania CLE 1158 (with a horizontal line); CIL II 2/7, 567 (with a hedera). For further details and examples see Limón, La compaginación (above n. 30) 47–53 and 98–100.

[35] Nach Prüfung eines Abklatsches aus dem Jahr 1934, der im Archiv der ÖAW verwahrt wird, steht die Lesung KA m.E. fest; in LIA wird I’ A’ transkribiert, ohne Vorschlag einer Deutung.

[36] So bemerkt Velius Longus (frühes 2. Jh. n.Chr.) in seinem Liber de orthographia, daß manche die Regel aufstellen würden, daß Nomina auf CA- im Anlaut mit KA- geschrieben werden sollen: [litteram k] necessariam putant esse nominibus quae cum a sequente hanc litteram inchoant (Gramm. Lat. VII 53, 12–13); vgl. ThLL III 502, 30–40 s.v. carus.

[37] Vgl. ThLL III 155–156 s.v. caligatus.

[38] Nouveaux documents sur la présence militaire dans la colonie julienne augustéenne de Simitthus (Chemtou, Tunisie) , CRAI 135 (1991) 833, n◦ 4.

[39] Khanoussi, op. cit., 833 Anm. 17.

[40] Eine Zusammenstellung der epigraphischen Evidenz zu Elagabal bietet L. de Arrizabalaga y Prado, The Emperor Elagabalus. Fact or Fiction?, Cambridge 2010, 350–351 (Appendix 4). Von 153 Inschriften bezeugen 80, also fast die Hälfte des gesamten Materials, die damnatio memoriae. Die unterschiedlichen Abstufungen, sprich die Variationen der Tilgungen, fasst Arrizabalago y Prado auf S. 118 zusammen. Als einzige Parallele für die Tilgung einzelner Titulaturelemente lässt sich eine Inschrift aus Britannien anführen, nämlich CIL VII 585 = RIB 1465, worin das Cognomen Antoninus, die Epitheta P(ius) F(elix) sowie der Titel Sacerdos Ampliss(imus) Dei Invicti Solis Elagabali getilgt wurden.

[41] Für diesen wichtigen Hinweis sei meinem Kollegen Olivier Gengler (Universität Wien) herzlichst gedankt.

[42] Vgl. dazu etwa AE 1981, 909 (Numidia) ([[Imp(eratori) Caes(ari)]] di/vi Antonini / Magni [[filio]]) oder CIL VIII 10308 + p. 2138 (Numidia), wo nur [[fil(ius)]] getilgt wurde. Weitere Beispiele zu Elagabal führt De Arrizabalago y Prado, Elagabalus (o. Anm. 38) 118 mit Anm. 262 an.

[43] Zu dieser Filiation siehe etwa D. Kienast, Römische Kaisertabelle, Darmstadt 32004, 177.

[44] Vgl. etwa AE 1981, 902 (Numidia).

[45] So etwa der mater castrorum-Titel oder die Bezeichnung als mater Augusti wie in CIL VIII 1313 = 14816 (Africa proconsularis) und CIL VIII 18254 = 18257 = AE 1967, 573 (Numidia).

[46] Die letzten drei Zeilen der Weihinschrift, zu deren Lesung und Ergänzung es bislang ebenfalls keine Vorschläge gibt, liefern keine Hilfestellung zur Rekonstruktion der Zeilenlänge. Zu Z. 3 sei allerdings angemerkt, dass am Ende der Zeile nicht AVXIL, sondern eher AVXIT, vielleicht noch gefolgt von einem weiteren finiten Verbum, zu lesen ist. Für diesen Hinweis danke ich Hans Taeuber (Universität Wien).