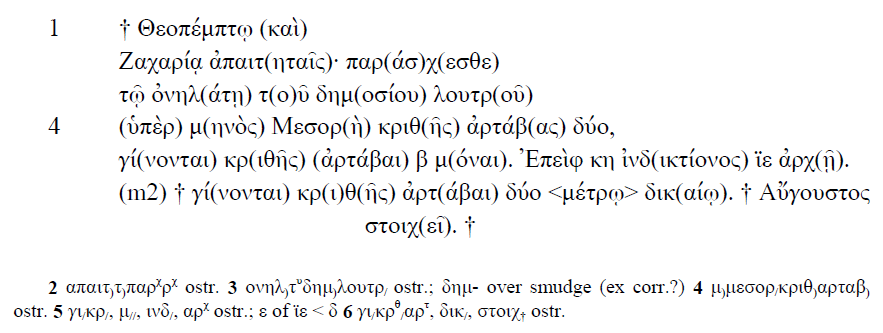

Todd M. Hickey

A Misclassified Sherd from the Archive

of Theopemptos and Zacharias (Ashm. D. O. 810)*

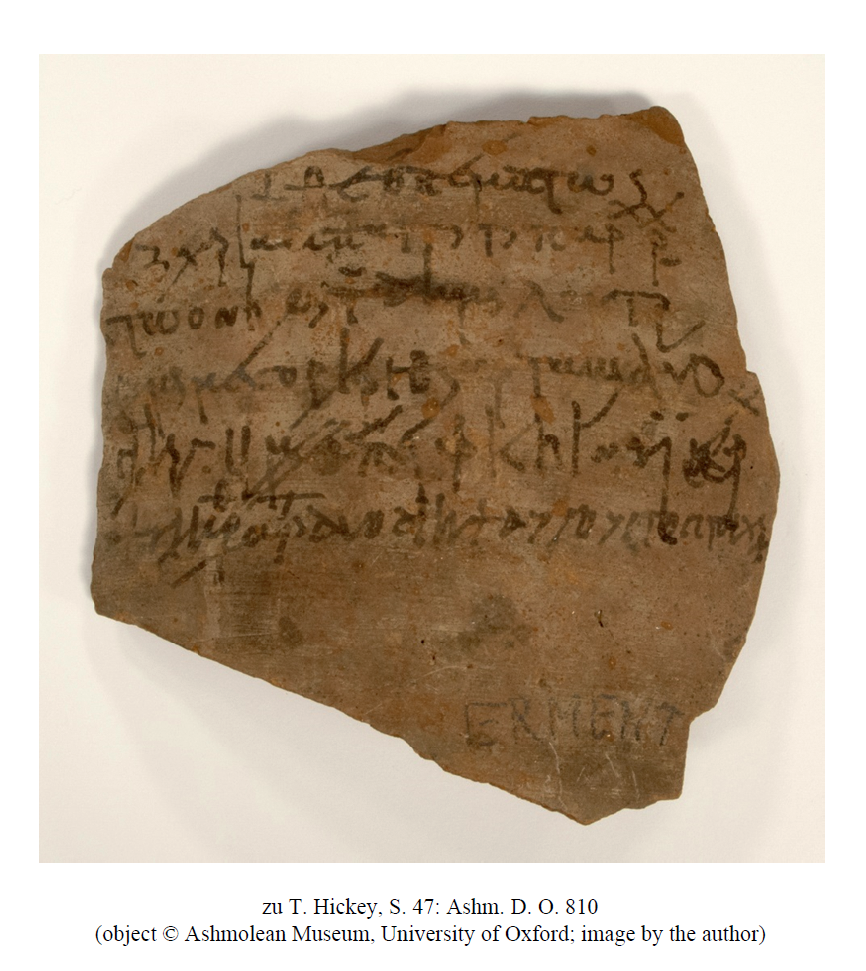

Plate 2

Ashmolean Museum D(emotic) O(strakon) 810 is not an Egyptian-language text at all but an order for payment from the large Greek archive of Theopemptos and Zacharias. Though the texts in this assemblage largely lack variety — the new Ashmolean text might be considered emblematic of the vast majority of the pieces[1] — the archive has attracted significant scholarly attention, principally because it dates to the brief Sasanian occupation of Egypt (619‒629); see further P.Oxy. LV 3797, 9 n. (last paragraph); B. Palme, Das Amt des ἀπαιτητής in Ägypten (MPER N.S. 20), Vienna 1989, 262‒263; Cl. Foss, The sellarioi and Other Officers of Persian Egypt, ZPE 138 (2002) 171‒172; P. Sänger, Saralaneozan und die Verwaltung Ägyptens unter den Sassaniden, ZPE 164 (2008) 197‒199; and most recently, O.Petr.Mus. III, pp. 637‒639.

Ashm. D. O. 810 is an order to pay two artabai of barley to the donkey driver of the public bath of an unspecified locale. Its closest parallel in the archive is O.Petr.Mus. 539, which requests the same amount of grain for the same recipient,[2] was written in the following month (viz., Mesore) of the same indiction, likewise addresses both Theopemptos and Zacharias as apaitētai, and has the same signatory (Augoustos).[3] The primary hand of the two texts is not identical, however, [4] and other differences include the order of the names (Theopemptos comes second in the Petrie sherd) and the presence of an addition specifying the purpose of the barley (539 inserts εἰς ἀποτροφὴν τῶν ἀλόγ⟦ο⟧ων̣ in l. 4).

Ashm. D. O. 810 is a piece of ribbed pottery with noticeable inclusions in its fabric. The sherd’s core is a dark sand color, while its margins are reddish brown. It has a sand-colored slip. The text on the sherd runs parallel to the rotation lines. Its inventory number appears on its back, as does its acquisition number, 569.1892. The second half of the acquisition number indicates that the piece arrived in the collection in the same year as the Ashmolean ostraka from the archive that were classified as Greek (O.Ashm. 96‒101 = 545, 512, 526, 511, 478, 567.1892). The source for all seven of these Ashmolean sherds was the Reverend Greville Chester.[5] Chester’s notes reveal that O.Ashm. 96 and 100 were acquired at Armant (Hermonthis),[6] a purchase locus that would seem to be corroborated by D. O. 810, which has “ERMENT” written in pencil on its front (cf. image).[7] The place of purchase need not, however, correspond to the provenance or findspot of the archive, even in the case of material offered for sale at a local (as opposed to national) market, though one might expect ostraka to be less likely to travel.[8] Internal evidence from the archive, specifically the references to a δημόσιον λουτρόν, suggests an urban context,[9] but this does not, of course, exclude Hermonthis.[10] Foss has questioned the Hermonthite provenance on the basis of the administrative structure that it implies, preferring an origin in the province of Arcadia (see Foss, Sellarioi [cit. above] 172, for details); a chronological formula in the new Ashmolean sherd, however, points to the Thebaid (see 5 n. below).[11]

![]()

2 απαιτ)τ)παρχρχ ostr. 3 ονηλ)τυδημ)λουτρ/ ostr.; δημ- over smudge (ex corr.?) 4 μ)μεσορ/κριθ)αρταβ) ostr. 5 γι/κρ/, μ//, ινδ/, αρχ ostr.; ε of ϊε < δ 6 γι/κρθ /αρτ, δικ/, στοιχ† ostr.

“To Theopemptos and Zacharias, apaitētai: Supply to the donkey driver of the public bath for the month Mesore two artabai of barley, total 2 art. barley exactly, Epeiph 28, indiction 15, at its beginning. (2nd hand) Total two artabai of barley by correct [measure]. Augustus assents.”

1 †: The cross is used inconsistently in the archive. Its complete absence is verifiable (on an image) in, e.g., O.Ashm. 96 and O.Petr.Mus . 541 (which have different principal scribes). Prima facie, it is tempting to associate omission with the Sasanian occupation, but if Persian sensitivities were the cause, why does the cross appear in texts like O.Bodl. II 2125 and 2126, which concern Sasanian personnel (cf. O.Petr.Mus., p. 638)? In regard to this question we might also note the continued presence of the cross on the copper coinage minted during the occupation; cf. Ph. Grierson, Byzantine Coins, Berkeley 1982, 118. (Some have attributed the coins in question to Anastasius; against this see M. Metlich and N. Schindel, Egyptian Copper Coinage in the 7th Century AD: Some Critical Remarks, Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter 179 [2004] 12.) The publication of images of all of the texts in the archive may well yield a solution. For the moment, I note that the signatory Theon seems never to have used the cross (even when the text’s principal scribe did; cf. O.Bodl. II 2130 and 2486).

Θεοπέμπτῳ: Outside of the archive under discussion here, this is a relatively uncommon (and late) name; see P.Amst. I 57.1‒2 (= SB XII 11138; provenance unknown, VI); P.Köln VI 281.2 (provenance unknown, VI); P.Mich. XI 613.2 (Herakleopolite, 19.viii.415); P.Naqlun I 9.28, 29, 36 (Θεοπέμτου is the form that appears; VI); P.Rein. II 107.6 (Koptite, 27.iii.573/588/603 [+ BL XI 186]); PSI XVI 1640.2 (Antinoopolite?, end VI); P.Sorb. II 69/76F(x2), 111D1 (Hermopolite, ca. 618‒619/ca. 633‒634); P.Stras. V 330.1‒2 (Θεόπεμτος is written; provenance unknown, V); SB VI 9616.22, 30 (Antinoopolite, 10.viii.550‒558?), XIV 12085.14 (provenance unknown, V); and SB Kopt. II 843.2 ([ⲑ]ⲉⲟⲡⲙ̅ⲡⲧⲟⲥ), 6 (ⲑⲉⲟⲡⲉⲙⲡⲧⲉ; Antinoopolite?, VII?). Regarding SPP XX 113.9 (provenance unknown, 26.ix.401), a check of the image reveals that the reading of the ed. pr. is correct (pace BL II.2 164); this is the earliest securely dated attestation of the name in the corpus of documentary papyri. The Alexandrian grave stele of Abba Theopemptos (SB III 6255.2‒3; 515) might also be noted, as might the fifth-century bishops of Kabasa and Nikiou in the Delta (cf. K. A. Worp, A Checklist of Bishops in Byzantine Egypt, ZPE 100 [1994] 300, 303).

2 ἀπαιτ(ηταῖς): Palme, Amt (cit. above), is the standard reference. In the archive, the office is also associated with Theopemptos and Zacharias in O.Petr.Mus. 529.2 (26.v‒24.vi.625; word abbreviated in the same manner as it is in D. O. 810), 531.2 (ca. 623‒631), 532.3 (623‒627; word abbreviated in the same manner as it is in D. O. 810), 534.2 (1.iv.626; word abbreviated in the same manner as it is in D. O. 810), 539.2 (12.viii.626 [HGV: 627]; word abbreviated in the same manner as it is in D. O. 810), and O.Bodl. II 2124.2 (12.v.624; information from Gonis); the designation probably also appeared in O.Ashm. 97.2 (cf. n. ad loc. + BL IX 397) and O.Bodl. II 2129.2 (cf. n. ad loc.). Palme, Amt (cit. above) 262‒263 prudently queried to what extent the office should be ascribed to Theopemptos and Zacharias. O.Petr.Mus. 539.2 (a reedition of O.Petr. 431), which speaks of the pair as “apaitētai of the 13th indiction” and is dated to the 15th indiction, now implies that they were held over in office. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that none of the archive texts that mention the office and possess secure indiction dates were written before the thirteenth indiction (624/625). In light of this, I would suggest that O.Petr.Mus. 531 and 532 be dated to the thirteenth indiction or later; the same may be said of O.Ashm. 97 and O.Bodl. II 2129 if ἀπαιτηταῖς appeared in them. (It may well be that not a single text in the archive predates the thirteenth indiction; a study photograph from Gonis indicates that O.Ashm. 96 dates to the 14th, not the 11th, indiction.) A Theopemptos and Ioannes appear as apaitētai of the holy church in O.Bodl. II 2136 (information from Gonis; note also II 2487); if, as seems likely, the former is our man, it may mean that his work with Zacharias also occurred under ecclesiastical authority. (In such a context, the absence of the cross [see 1 n. above] would be all the more striking.)

παρ(άσ)χ(εσθε): It is unclear whether the horizontal stroke near the tail of the second rho of παρχρχ is merely a stray or intentional (e.g., an attempt to make a staurogram).

3 ὀνηλ(άτῃ) τ(ο)ῦ δημ(οσίου) λουτρ(οῦ): The barley ordered by the sherd is likely fodder for the donkeys of the onēlatēs; no doubt the donkeys themselves were primarily tasked with bringing fuel to the bath (but note SB XVI 12471.5‒9 along with the commentary in J. D. Thomas,Unedited Merton Papyri II, JEA 68 [1982] 286). Cf. P.Cair.Zen. II 59292.28‒29, 96‒98 (note the barley in both entries), P.Brem . 47, and BGU I 14/3.17‒19.

5 ἰνδ(ικτίονος) ϊε ἀρχ(ῇ): The word order here seems to appear only in the Thebaid; cf. O.Sarga 173.7 (VI‒VII), P.KRU 36.2‒3 (4.vi.724 + BL V 96 [see SB I 5572]), 106.246 (31.v.734 + BL VII 188 [see SB I 5609]). For ἀρχῇ, see R. S. Bagnall and K. A. Worp, Chronological Systems of Byzantine Egypt, Leiden 22004, 22‒35, esp. 25‒26, 30 (for usage in the Thebaid). Gonis informs me that ἀρχ(ῇ) recurs in O.Bodl. II 2124.6 (12.v.624).

6 <μέτρῳ> δικ(αίῳ): See P.Heid. V, p. 321. This phrase seems preferable to the anachronistic <μετρήσει> δικ(αίᾳ), which was suggested for O.Ashm. 99.4, 5 (n. ad loc.) and retained without comment by the editor of O.Petr.Mus. 528 and 530 (who does not translate it because he elides the recapitulations in the texts). δικ(αίῳ) also appears, abbreviated in a slightly different fashion (probably due to limitations of space), in O.Bodl. II 2124.6 (information from Gonis).

Αὔγουστος: Also the signatory in O.Ashm. 99.6 (9.viii.625); O.Bodl. II 2125.6‒7 (6.iv.626), 2133.7 (11.viii.625); O.Petr.Mus. 528.5‒6 (ca. 623‒631, but see 2 n. above), 530.8‒9 (10.viii.625; ϊνδ/ ιδ is missing from the transcription at the end of l. 5 [indicated to me by Gonis]), 532.12 (Pauni 24; 623‒627, but see 2 n. above), 533.5 (10.viii.626), and 539.8 (12.viii.626 [HGV: 627]). For the dates of O.Ashm. 99 and O.Bodl. II 2133, I follow the corrections of Gonis, who informs me that O.Bodl. II 2126 (2.iv.626), 2128 = 2489A (9.viii.625), 2131 (15.iv.626), 2132 (24.iv.626), and Ashm. G. O. inv. 510 (no date preserved) likewise have Augustus as signatory. The last three of these additional texts reveal that he was a dioikētēs and show him signing through an intermediary (a man named Besarion in 2131 and 2132). Augustus is first attested (securely) on 9.viii.625 (14th indiction), while his latest sure date is 12.viii.626 (15th indiction). Other archive signatories were active during the same period, e.g., Theon (cf. O.Petr.Mus. 541 [2.iv.626, the same day as Augustus in O.Bodl. II 2126]). The clustering of Augustus’ activity in the months of Mesore and Pharmouthi (with the exception of O.Petr.Mus. 532 [Pauni] and D. O. 810 [Epeiph, but late in the month and concerning a payment for Mesore]) might seem noteworthy, but cf. O.Petr.Mus., pp. 637‒638, which presents the month dates for the archive as a whole.

Outside of an imperial context, the name Augustus is rare; beyond the archive discussed here, I can point only to P.Stras. VII 691.22 (where the reading is uncertain and inspired, it seems, by a bad entry in Foraboschi’s Onomasticon).

- - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri |

Todd M. Hickey |

* I thank Andreas Winkler for bringing D. O. 810 to my notice during his survey of the demotic ostraka in the Ashmolean Museum; Liam McNamara, the Ashmolean’s keeper for its collections from ancient Egypt and the Sudan, for permission to photograph the sherd and publish it; and Nikolaos Gonis, who kindly shared notes from his forthcoming (re)edition of the Oxford ostraka from the archive with me. (Gonis knew of D. O. 810 under its accession number through a transcription made by W. E. Crum, but he understandably could not locate it because it was stored among the demotic sherds. With characteristic generosity, he encouraged me to go ahead and submit this article after the “dots were connected” in the eleventh hour.) Dates and provenances follow HGV unless otherwise indicated.

[1] Pieces meriting more scrutiny (by virtue of their contribution to the interpretation of the archive) include O.Bodl. II 2136, 2487, and O.Petr.Mus. 529. A synthetic treatment, however, must await Gonis’ publication concerning the Oxford texts.

[2] On the digital image of O.Petr.Mus. 539, I am inclined to read τῷ ὀνηλ(άτῃ) instead of τοῦ (l. τῷ) ὀνηλ(άτῃ) at the beginning of l. 3.

[3] None of the editions of texts from the archive indicate hand shifts, but one clearly occurs in O.Petr.Mus. 539 at l. 8. The subscription of Augoustos there is certainly by the same hand that wrote the subscription in D. O. 810.

[4] Cf. O.Bodl. II, p. 372, “Il y a plusieurs écritures, qui vont de l’onciale à la cursive.” A study of the archive’s hands will need to await Gonis’ publication concerning the Oxford sherds from the assemblage. O.Petr.Mus. 534 (1.iv.626) seems, in any case, to have the same primary hand as D. O. 810.

[5] Regarding O.Ashm. 96‒101, see P.Oxy. LV 3797, 9 n. (last paragraph); Liam McNamara furnished the acquisition information for D. O. 810 (e-mail, 4 June 2013). For Chester, see W. Dawson and E. Uphill, Who Was Who in Egyptology, London 31995, 96‒97, and more germanely to the object under discussion here, G. Seidmann, The Rev. Greville John Chester and ‘The Ashmolean Museum as a Home for Archaeology in Oxford’, Bulletin for the History of Archaeology 16.1 (2006) 27‒33.

[6] Cf. P.Oxy. LV 3797, 9 n. (last paragraph).

[7] A study image of O.Ashm. 96 provided by Gonis shows that this sherd has an identical inscription in pencil.

[8] The editor of O.Petr.Mus. does not query the Hermonthite provenance of the archive. For the presence of external antiquities in local markets, cf., e.g., the case of the dossier of the Oxyrhynchite landowner Flavia Anastasia, most of which was purchased at Ashmunein (see T. M. Hickey, Reuniting Anastasia: P.bibl.univ.Giss. inv. 56 + P.Erl. 87, APF 49 [2003] 199). O.Var., p. 71, presents an example pertinent to ostraka. A careful study of the movement of papyri and related objects through the antiquities market would be very welcome.

[9] For δημόσιος as a signifier of a metropolite location, cf. B. Méyer,L’eau et les bains publics dans l’Égypte ptolémaïque, romaine et byzantine, in: B. Menu (ed.), Les problèmes institutionnels de l’eau en Égypte ancienne et dans l’Antiquité méditerranéenne, Cairo 1994, 277. But though the equivalence of δημόσιος and “municipal” (or “civic”) is well established for Late Antiquity (see, e.g., Fachwörter, s. v.), it seems imprudent, in my view, to rule out village settings completely, all the more so in light of the inconsistency and imprecision with which the Greek word was used (cf. A. Bowman, Public Buildings in Roman Egypt, JRA 5 [1992] 500). For δημόσιος as the source for the early Arabicdīmās, “bath,” see S. Denoix, Des thermes aux hammams: Nouveaux modèles ou recompositions?, in: M.-F. Boussac et al. (ed.), Le bain collectif en Égypte, Cairo 2009, 17‒18.

[10] For public baths at Hermonthis, cf. O. Mond and R. H. Meyers, The Temples of Armant: A Preliminary Survey, London 1940, 5, 10 (and pl. 1).

[11] The ἁγία ἐκκλησία mentioned in the archive’s O.Bodl. II 2487.2 (cf. also II 2136.2) is not responsive for the issue of provenance; cf. E. Wipszycka, καθολική et les autres épithètes qualifiant le nom ἐκκλησία : Contribution à l’étude de l’ordre hiérarchique des églises dans l’Égypte byzantine, JJP 24 (1994) 191‒212.