Sofie Waebens

When Two Fragments Meet

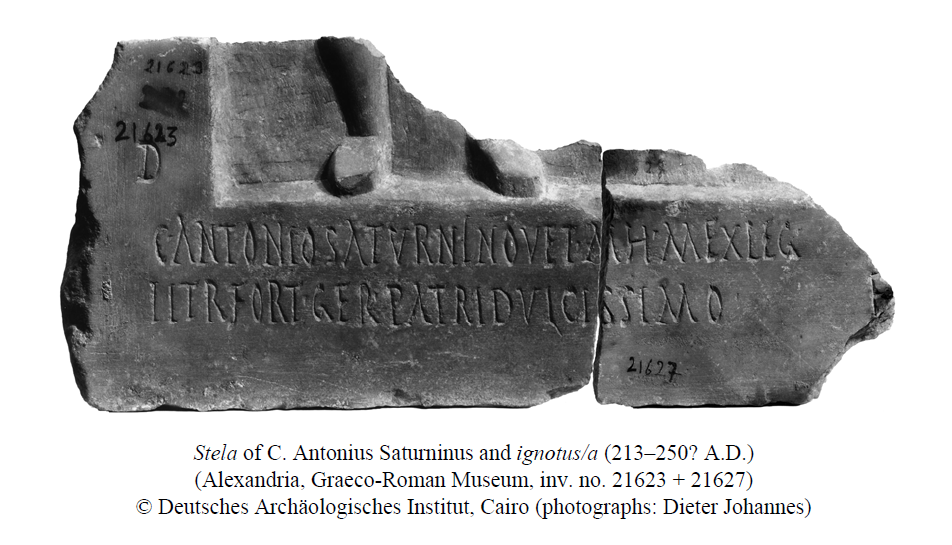

A Funerary Stela for Two People from Roman Egypt (Nikopolis)*

Tafel 15

Following the defeat of Marc Antony and Cleopatra VII by Octavian in the Battle at Actium in 31 B.C., a fortress was established southwest of the newly founded town of Nikopolis near Alexandria, which remained in use until at least the sixth century. [1] Its necropolis was located close to the fortress and gathered funerary monuments of the soldiers and their close relatives. Most tombstones are made of white or grey blue-veined marble, presumably from Asia Minor, some of limestone, alabaster or granite. More than 140 tombstones, most associated with legio II Traiana fortis, [2] come from this military burial site at Nikopolis. Only a small minority has been discovered in situ; the major part has been sold on the antiquities market in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. As a result, the tombstones are now scattered among various museum collections (Alexandria, Port Said, Suez, Cairo, Tanta, Baltimore, Brooklyn, Athens, Brussels, Marseille, Paris, Warsaw, Bologna, London, Stockholm, Uppsala, Edinburgh and Barcelona). In the course of my research on these funerary monuments from Nikopolis, [3] I have been able to join two fragments of a funerary stela set up for two people, a veteran of legio II Traiana fortis and an ignotus/a, kept in the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria under inventory numbers 21623 and 21627. Previous editors have published these fragments separately. I therefore provide a revised edition here.

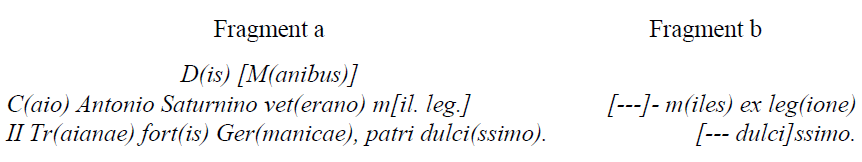

The fragments (a with inv. no. 21623, b with inv. no. 21627) have been discovered in the late nineteenth century at Sidi Gaber, the modern name of the area where the fortress and nearby necropolis may have been.[4] Dr. Alfred Osborne (1865–1933), the renowned ophthalmologist and collector of antiquities,[5] donated them to the Graeco-Roman Museum (Alexandria) in 1923. The two fragments were once part of a coarse-grained, white marble funerary stela bearing a representation of the deceased. Despite being broken on all edges except the bottom, the fragments are in good condition with only slight chipping along the bottom edges and minor surface damage. The inscribed face of the stela is smoothly dressed, but the background plane of the relief scene was left roughly finished with the chisel. The first editor, E. A. Breccia, published these fragments as follows:[6]

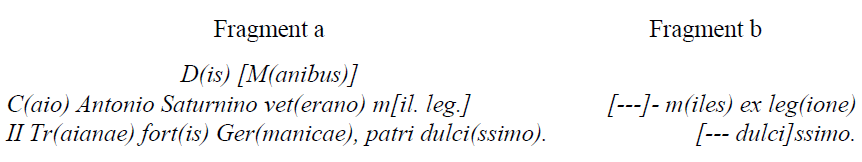

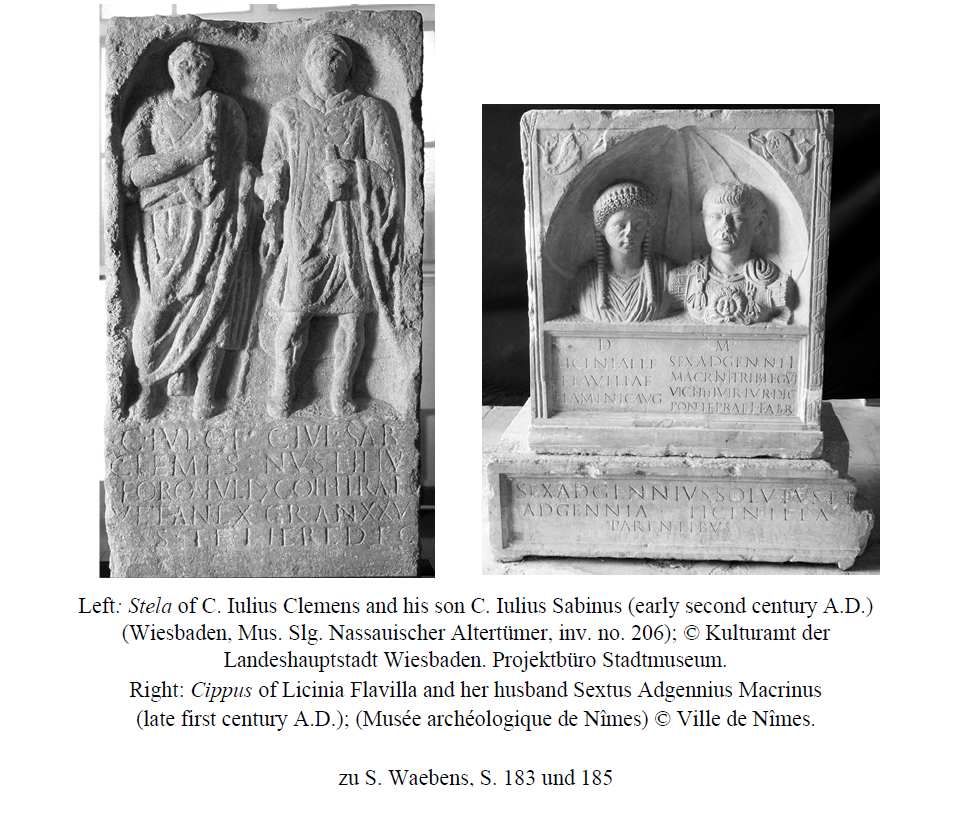

The fragments have also been included in Schmidt’s recent catalogue of funerary monuments from Alexandria, Nikopolis, Terenouthis and Oxyrhynchos in the Graeco-Roman Museum.[7] He read a previously unnoticed letter at the right edge of fragment b, which suggests that two Latin inscriptions were carved underneath the relief scene in two columns (for close parallels, see plate 15). Not one but two full-length standing figures were thus depicted on the monument. His discovery resulted in a new edition:

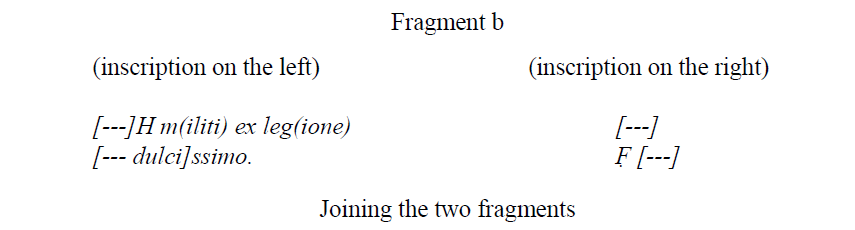

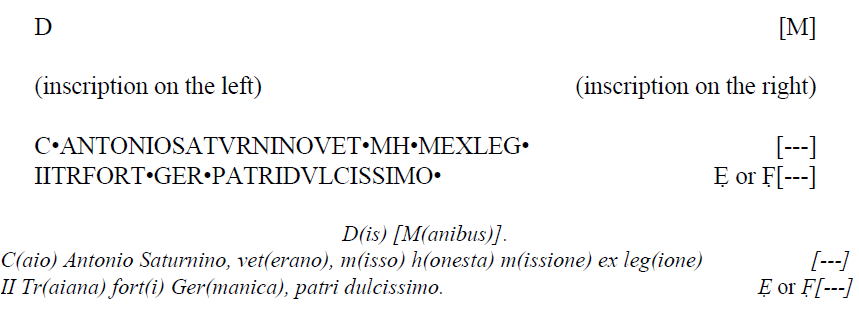

While editing the Nikopolis tombstones, I was struck by the fact the last lines of fragments a and b fit together, leading me to consider the possibility that the two fragments were in fact part of the same funerary monument. As it was impossible to check this in person due to continuing major renovation work at the Graeco-Roman Museum, digital photographs of the fragments were scanned at comparable scales and merged to produce a photograph of the two fragments joined, as seen on plate 15. This image clearly shows that these fragments fit together. The dimensions (a: 20.2–14.0 x 13.9–29.7 x 3.2 cm, b: 14.0 x 15.8 x 3.1 cm) and letter heights (a: 2.1 cm, b: 2.1–2.3 cm) recorded for the two pieces support their join. The two fragments also display a similar lettering style (scriptura actuaria). We thus have a single funerary monument comprising two inscriptions, carved underneath the relief scene on the left and right: the inscription on the left is complete (the join does not obscure the letters M and S in l. 2–3), but only one letter of the inscription on the right is partly preserved. It remains therefore uncertain whether E or F should be read. Two people were commemorated: C. Antonius Saturninus, a veteran of legio II Traiana fortis,[8] and an ignotus/a, probably a close relative. The relief, set in a niche, may have taken up almost the entire surface of this funerary stela, as on most Nikopolis stelae, but only the feet and lower right leg of the man on the left, representing C. Antonius Saturninus, survive. When joining fragments a and b, the texts read as follows:

L. 2: many soldiers bearing Saturninus as cognomen are known from Egypt, including Iulius Saturninus, centurio of legio III Cyrenaica (CIL III 6599 of c. 80 and 6603 of 80), C. Iulius Saturninus, soldier of cohors III Ituraeorum (P.Oxy. VII 1022 = CPL 111 = CEL I 140, dating after 24 February 103) and Barbius Saturninus, polio of legio II Traiana fortis (CIL III 141261 of 213–?250). [9]

Numerous parallels for the formula missus honesta missione ex, followed by the veteran’s unit, can be found in inscriptions, especially from Rome (e.g. CIL VI 2511, 2515, 31009; CIL VIII 5180, cf. 17266; CIL X 1753; CIL XII 1749; CIL XIII 1838, 1901). [10]

The initial formula, of which only the first letter survives (D), flanks the bottom of the relief scene. The inscription on the left is carved in good quality letters with some rustication (especially notable in the A without crossbar, M, F and T). The horizontal bar of the L in l. 3 is curvilinear, unlike the L in l. 2. The A’s in l. 2 are slightly taller than the other letters. A tall I occurs in the same line. AE 1925, 63,[11] a fragment of a funerary stela set up for Aurelius Quintianus, candidatus of legio II Traiana fortis, offers a close parallel for this inscription in lettering. Faint traces of guidelines can be seen above and below l. 2–3. Triangular interpuncts end all lines but separate words intermittently. The inscription is unusual for the absence of the commemorator: 18 of the 19 inscriptions (excluding the most fragmentary) set up for soldiers or veterans of legio II Traiana fortis from Nikopolis record this information.[12]

The epithet Germanica, bestowed upon legio II Traiana fortis for its achievements in Caracalla’s war against the Alamanni in 213,[13] provides a terminus post quem of 213 for this monument. The laudatory adjective, dulcissimus, is consistent with this date. Since most figural stelae from Nikopolis date to the first half of the third century, the terminus ante quem is likely 250.

The figural stelae from Nikopolis usually portray only one person, although there are exceptions:

(1) AE 2002, 1586 (= GIBM IV, 2 1113; JJP 32 [2002] 45–48; AKB 35 [2005] 65–76; SEG LII 1762; CE 87 [2012] 343–360): two full-length standing male figures are portrayed on the relief. The man on the left, recently identified as the son of the deceased, a veteran, [14] is dressed as a soldier, while the man on the right, his right hand reaching for the plume of a helmet placed on top of a case surrounded by sword and shield, wears a tunic and toga (188/189). [15]

(2) AE 1980, 895 (= ZPE 38 [1980] 119–124 no. 2; Schmidt, Grabreliefs [cit. n. 7] 130–131 no. 116, Taf. 41): M. Aurelius Paullus and Aurelia Iulia Epictesis, the 12-year-old son and 35-year-old wife of Aurelius Timocrates, a soldier of legio II Traiana fortis, are represented on the relief (212–?235).

(3) Schmidt, Grabreliefs (cit. n. 7) 129 no. 111, Taf. 39: a child, shown in three quarter profile, looks up adoringly towards a man dressed as a soldier, holding his right hand. Due to damage, it remains uncertain whether the deceased was a soldier of legio II Traiana fortis or the young son of an anonymous soldier of legio II Traiana fortis, as St. Schmidt assumes (222–?250).

(4) Unpublished (without inscription; for a photograph, see Schmidt, Grabreliefs [cit. n. 7] 42 Abb. 41; AKB 35 [2005] 69–70 Abb. 3.1): two boys, one dressed as a soldier, are shown on the relief. Due to the absence of an inscription, the identification of the boys remains uncertain, although they were probably the children of a soldier or, less likely, veteran stationed at Nikopolis (222–?250).

What is unusual about the stela discussed in this paper is the commemoration of the deceased in individual inscriptions, carved underneath the relief in two columns. (2) depicts the deceased commemorated in the same inscription underneath the relief, [16] as on most figural stelae set up for two or more people (familial commemoration is, for instance, particularly common on third-century Danubian stelae).[17]

The importance of this funerary stela lies in the fact that it is one of the few funerary monuments set up for a veteran from Nikopolis. Only four other monuments are so far known:

(1) CIL III 6607 (= ILS I 2247; BIE 12 [1872/1873] 118; Athenaion 2 [1874] 422 no. 3): C. Niger, missicius, and M. Longinus, miles of legio III Cyrenaica (early first century, no relief).

(2) CIL III 14139 (= E. A. Breccia, Iscrizioni greche e latine [Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du musée d’Alexandrie 57], Cairo 1911, 221 no. 489): L. Vettius Vale[---], veteranus ex duplicario of ala I Thracum Mauretana (late first century, no relief).

(3) SB I 2477 (= RA 18 [1891] 341 no. 13): Heliodoros, οὐετρανὲ ἐντείμως ἀπολελυμένε (second or third century?, no relief). [18]

(4) AE 2002, 1586 [see (1) above]: Ares, παυσάμενος στρατιᾶς (188/189, with relief).

This small number of monuments from Nikopolis[19] suggests that few veterans settled near the fortress where they had been garrisoned. From the late first century onwards, when soldiers were usually locally recruited, the majority may have either returned to their native towns (most notably Alexandria)[20] or moved to villages in the countryside after their discharge.[21]

- - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - -

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven |

Sofie Waebens |

* This paper was made possible by a grant of the Research Fund (Onderzoeksfonds) KU Leuven, for which I here extend my warmest thanks. I am grateful to Katelijn Vandorpe for useful suggestions and Mervat Seif el-Din, previous director of the Graeco-Roman Museum (Alexandria), for permission to publish the fragments in a letter dated 4 March 2009. I would also like to thank Franziska Beutler and the two anonymous reviewers of Tyche for their comments on the material discussed. Tom Gheldof has produced the photograph of the two fragments joined together.

[1] J. G. Wilkinson, Modern Egypt and Thebes: Being a Description of Egypt, Including the Information Required for Travellers in that Country I, London 1843, 172; J. Murray, A Handbook for Travellers in Lower and Upper Egypt: Including Descriptions of the Course of the Nile through Egypt and Nubia, Alexandria, Cairo, the Pyramids, Thebes, etc. (Murray’s Foreign Handbooks), London 61880, 141; A. Adriani, Repertorio d’arte dell’Egitto greco-romano. Serie C, Palermo 1966, 102; R. Alston, Soldier and Society in Roman Egypt. A Social History, London 1995, 193.

[2] By 5 February 127 at the latest (CIL III 79, cf. 141476 = W. Ruppel, Der Tempel von Dakke III, Cairo 1930, 21–23 no. Gr. 28), legio II Traiana fortis was stationed in the fortress, where it remained for the next three centuries. On this legion, see E. Ritterling, Legio (II Traiana), RE 12, 2 (1925) 1484–1493 and S. Daris, Legio II Traiana Fortis, in: Y. Le Bohec (ed.),Les légions de Rome sous le Haut–Empire I (Université Lyon III. Collection du Centre d’études romaines et gallo-romaines N.S. 20), Paris 2000, 359–363. For a general history of the garrison in Egypt, see most notably J. Lesquier, L’armée romaine d’Égypte d’Auguste à Dioclétien (MIFAO 41), Cairo 1918, 6–114; E. Ritterling, Legio, RE 12, 1 (1924) 1280–1281; H. M. D. Parker, The Roman Legions, Oxford 1928, 109–115; Alston, Soldier and Society (cit. n. 1) 163–191; R. Haensch, The Roman Army in Egypt, in: C. Riggs (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt, Oxford 2012, 68–82.

[3] This paper has its origins in my Ph.D. thesis on the legio II Traiana fortis tombstones from Nikopolis, entitled: Picturing the Roman Army in Third-Century Egypt. Tombstones from the Military Necropolis at Nikopolis, written under the supervision of Katelijn Vandorpe and Jon Coulston (St. Andrews) at the KU Leuven and currently under preparation for publication. The project ‘Life and death of legionary soldiers in third-century Egypt’, resulting in this Ph.D. thesis, was funded by the Research Foundation Flanders (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen).

[4] T. D. Néroutsos-Bey, L’ancienne Alexandrie. Étude archéologique et topographique, Paris 1888, 85; E. A. Breccia,Alexandrea ad Aegyptum. Guide de la ville ancienne et moderne et du musée gréco-romain, Bergamo 1914, 73–74; Lesquier,L’armée romaine (cit. n. 2) 390; Adriani, Repertorio (cit. n. 1) 101–102, 229 (with extensive bibliography); B. Tkaczow, The Topography of Ancient Alexandria. An Archaeological Map (Travaux du Centre d’archéologie méditerranéenne de l’Académie polonaise des sciences 32), Warsaw 1993, 174–175 no. 143.

[5] M. Meyerhof, Dr. Alfred Osborne, British Journal of Ophthalmology 18 (1934) 60.

[6] Fragment a: E. A. Breccia, Note epigrafiche, BSAA 20 (1924) 269 no. 4, Fig. 12; fragment b: Ibid., 270 no. 9, Fig. 17 (erroneously listed with inv. no. 21527 instead of 21627).

[7] Fragment a: St. Schmidt, Grabreliefs im griechisch-römischen Museum von Alexandria (Abhandlungen des Deutschen archäologischen Instituts Kairo, Ägyptologische Reihe 17), Berlin 2003, 130 no. 114, Taf. 40 (referred to by L. Castiglione, Kunst und Gesellschaft im römischen Ägypten, AAntHung 15 [1967] 115 n. 38); fragment b: Ibid., 130 no. 115, Taf. 40.

[8] N. Criniti, Sulle forze armate romane d’Egitto: osservazioni e nuove aggiunte prosopografiche, Aegyptus 59 (1979) 214 no. 194a, to which add 252 no. 2256 due to the join of fragments a and b.

[9] The prosopographical information included in Lesquier, L’armée romaine (cit. n. 2) 518–551 and the prosopograhical studies of R. Cavenaile, Prosopographie de l’armée romaine d’Égypte d’Auguste à Dioclétien, Aegyptus 50 (1970) 213–320; N. Criniti,Supplemento alla prosopographia dell’esercito romano d’Egitto da Augosto a Diocleziano, Aegyptus 53 (1973) 93–158 and Criniti, Sulle forze armate romane (cit. n. 8) 190–260 should be supplemented with data from the People’s tool in Trismegistos (http://www.trismegistos.org). For general attestations of the cognomen Saturninus, see I. Kajanto, The Latin Cognomina, Helsinki, Helsingfors 1965, 18, 30, 54–55, 213; for attestations among legionaries in particular, see L. R. Dean, A Study of the Cognomina of Soldiers in the Roman Legions, Princeton 1916, 48–49, 273–278.

[10] For additional examples, see M. A. Speidel, Miles ex cohorte: Zur Bedeutung der mit ex eingeleiteten Truppenangaben auf Soldateninschriften, ZPE 95 (1993) 190–191.

[11] = Breccia, Note epigrafiche (cit. n. 6) 268–269 no. 3, Fig. 11 = Schmidt, Grabreliefs (cit. n. 7) 130 no. 113, Taf. 40. This fragment, found at Sidi Gaber, can be dated to the first half of the third century on the basis of nomenclature (twice Aurelius as nomen), formulation (impersonal centuria formula and bene merenti) and monument form (figural stela).

[12] An epigraphical analysis of the legio II Traiana fortis tombstones with Latin inscriptions is included in S. Waebens, Picturing the Roman Army in Third-Century Egypt. Tombstones from the Military Necropolis at Nikopolis, Leuven 2012, 267–273, Table IV.

[13] Ritterling, Legio (II Traiana) (cit. n. 2) 1488–1489, 1493; P. Sänger, Die Nomenklatur der legio II Traiana Fortis im 3. Jh. n. Chr., ZPE 169 (2009) 279–281.

[14] S. Waebens, Ares: Brother, Commander, Deity or Son? A New Interpretation of the Ares Tombstone, CE 87 (2012) 322–339.

[15] For this date, see A. Łajtar, A Tombstone for the Soldier Ares (Egypt, Late Antonine Period), JJP 32 (2002) 46; O. Stoll, «Quod miles vovit…» oder: Der doppelte Ares. Bemerkungen zur Grabstele eines Veteranen aus Alexandria, AKB 35 (2005) 68–69. This date is, however, debated; for a discussion, see AE 2005, 1609 and Waebens, Ares: Brother, Commander, Deity or Son? (cit. n. 14) 328–331.

[16] The inscriptions of (1) and (3) commemorate only one person; the second figure shown on the relief was therefore still alive when the monument was erected. In the absence of an inscription, we do not know whether the boys on (4) were both deceased.

[17] J. C. N. Coulston, Art, Culture and Service: The Depiction of Soldiers on Funerary Monuments of the 3rd Century AD, in: L. de Blois, E. Lo Cascio (eds.), The Impact of the Roman Army (200 B.C. – A.D. 476). Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects (Impact of Empire 6), Leiden 2007, 549 n. 83.

[18] The inscriptions commemorating soldiers and veterans from Nikopolis are rarely in Greek: SEG VIII 358 of 200–?250 and B. E. Thomasson, M. Pavese (eds.), A Survey of Greek and Latin Inscriptions on Stone in Swedish Collections (Acta Instituti Romani regni Sueciae, Series altera in 8° 22), Stockholm 1997, 117 no. 198, 118 Fig. 70 of 222–?250. SB I 4276 (= SEG VIII 438a, cf. XLVI 2112) of 300–?325 is in Greek, but uses the standard phrasing and structure of a Latin funerary inscription. SB I 979 of the first century is bilingual, while CIL III 6611, albeit in Latin, ends with εὐψύχι. For the use of Latin in the army in Egypt, see J. N. Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language, Cambridge 2003, 599–623.

[19] Compare with Apamea in Syria: merely 3 of the 140 funerary inscriptions (19 are too fragmentary to take into account), most of them associated with legio II Parthica, which was permanently stationed at Alba near Rome but deployed at Apamea on at least three occasions (215–218, 231–233 and 242–244), were set up for or by veterans. The publication of these inscriptions by J. Balty and W. Van Rengen is currently under preparation. I am grateful to the latter for providing a draft of this forthcoming edition.

[20] Alexandria is most often attested as origo in soldiers’ inscriptions, e.g. CIL III 6580, cf. 12045 (= F. Kayser, Recueil des inscriptions grecques et latines [non funéraires] d’Alexandrie impériale [Ier – IIIe s. apr. J.-C.] [Bibliothèque d’étude de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 108], Cairo 1994, 322–333 no. 105), a dedication made by the veterans oflegio II Traiana fortis to Septimius Severus in 194, as observed by G. Dietze-Mager,Der Erwerb römischen Bürgerrechts in Ägypten: Legionare und Veteranen, JJP 37 (2007) 41–73; R. Haensch,Der Exercitus Aegyptiacus – ein provinzialer Heeresverband wie andere auch?, in: K. Lembke, M. Minas-Nerpel, St. Pfeiffer (eds.), Tradition and Transformation. Egypt under Roman Rule (Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 41), Leiden 2010, 119–122; Haensch, The Roman Army in Egypt (cit. n. 2) 72–74.

[21] Alston, Soldier and Society (cit. n. 1) 48–52; F. Mitthof,Soldaten und Veteranen in der Gesellschaft des römischen Ägypten (1.–2. Jh. n. Chr.), in: G. Alföldy, B. Dobson, W. Eck (eds.), Kaiser, Heer und Gesellschaft in der römischen Kaiserzeit. Gedenkschrift für Eric Birley (Heidelberger althistorische Beiträge und epigraphische Studien 31), Stuttgart 2000, 377–406; P. Sänger, Römische Veteranen in Ägypten (1.–3. Jh. n. Chr.): Ihre Siedlungsräume und sozio-ökonomische Situation, in: P. Herz, P. Schmid, O. Stoll (eds.), Zwischen Region und Reich. Das Gebiet der oberen Donau im Imperium Romanum (Region im Umbruch 3), Berlin 2010, esp. 122–125; Id., Veteranen unter den Severern und frühen Soldatenkaisern: Die Dokumentensammlungen der Veteranen Aelius Sarapammon und Aelius Syrion (Heidelberger althistorische Beiträge und epigraphische Studien 48), Stuttgart 2011, esp. 19–25.