Nikos Litinas

Accounts Concerning Work of Weavers

Tafel 9

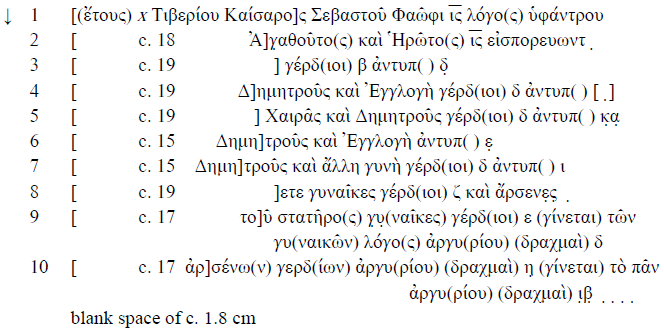

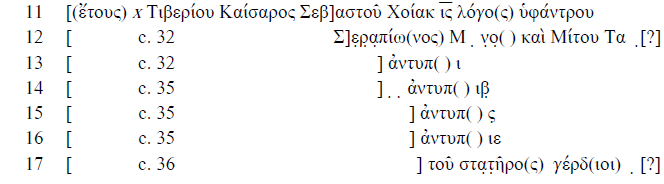

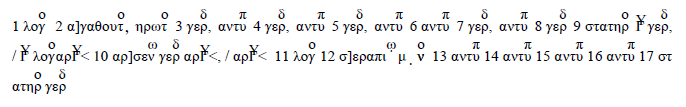

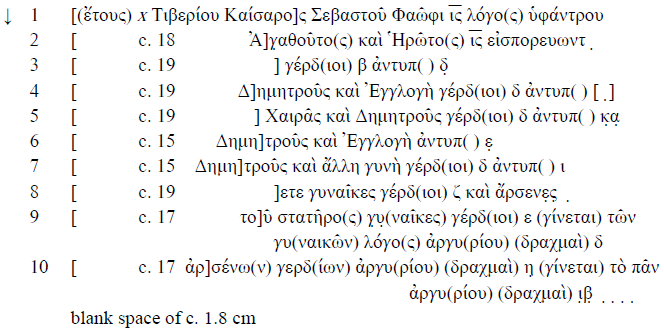

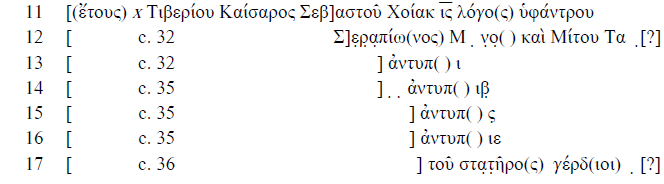

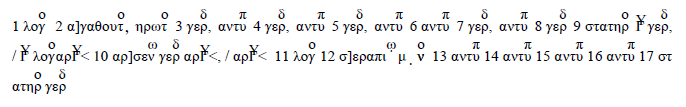

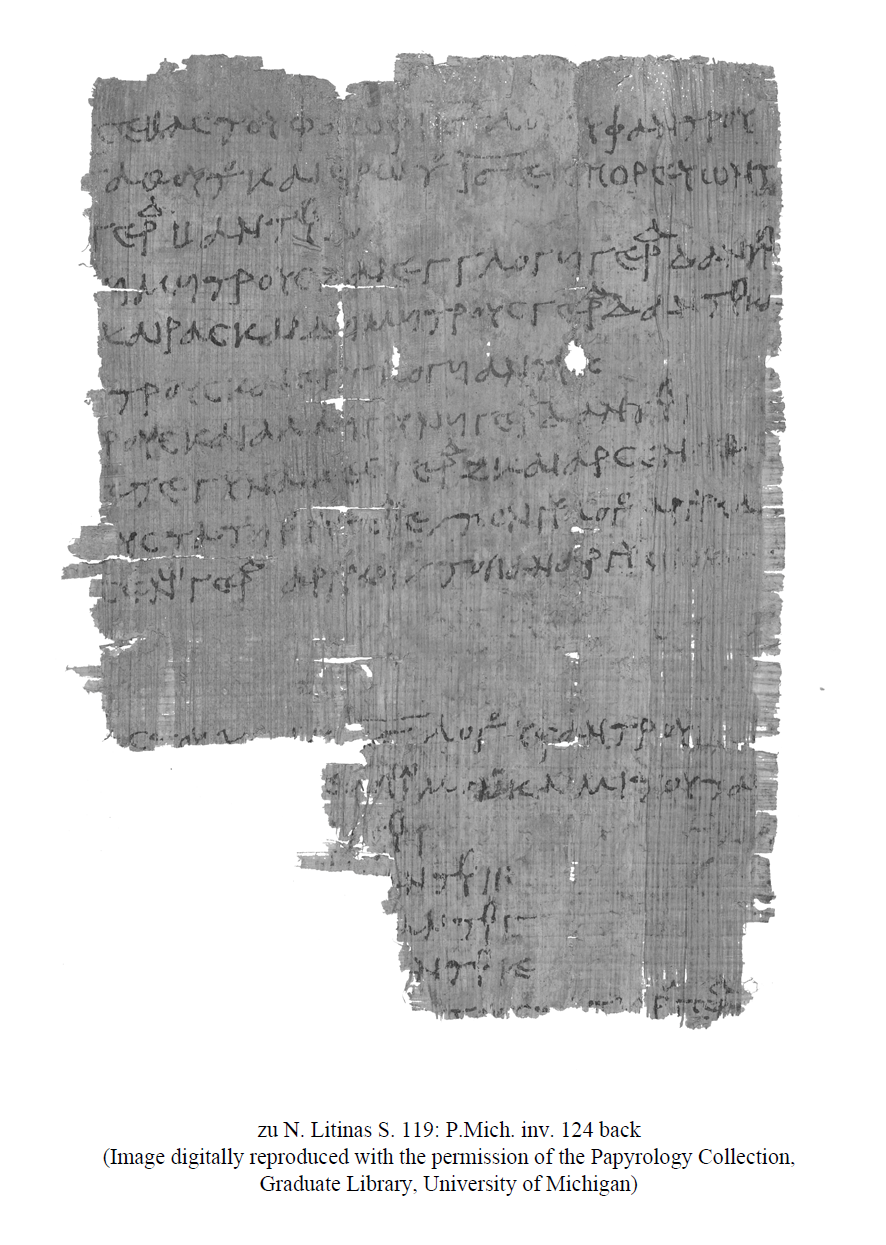

P.Mich. inv. 124 back 10.5 × 13.9 cm December of A.D. 35 or 36

Arsinoite nome? Plate 9

The front side of P.Mich. inv. 124 was published by E. Tov, “Two Documentary Papyri”, in ZPE 5 (1970) 17–20 (= SB X 10759) and preserves a joint declaration dated from the 20th year of Tiberius (A.D. 33–34), but probably this declaration was filed in A.D. 34–35 (see comm. to l. 1). Five brothers state that premises in the quarter of Dionysius’ Region in Arsinoe belong to them and declare themselves and their tenants as residents of the said premises. The text of the declaration is broken off at the right-hand side. About 20–25 letters per line have been lost up to l. 16 and what it is preserved is actually almost the half of the papyrus. It is questionable whether this piece of papyrus was the application which was submitted to the office of a laographos (Apollonios) or just a copy or draft which was kept in the house of the five brothers. In any case, sometime later (see comm. to l. 1) there was no need to keep the papyrus and the back side of this piece was reused (probably in the Arsinoite nome; see comm. to l. 2 concerning Ἡρῶτος). Someone wrote down an account (λόγος) of charges for weaving (ὕφαντρον). None of the names on the front appears on the back [1].

The main interest of this account lies in the word ἀντυπ( ). Only the word ἄντυπος is found in Greek to start with ἀντυπ- and its meaning “equal, similar or opposite” (see LSJ9 s.v. citing Hesychius, s.v.) does not make sense here. The same applies if we assume that this word was spelled wrongly, for instance, instead of ἀνθυπ( ) or ἀντιπ( ), even though some rare words like ἀντίπ(ονον), “return of labour, wages” (see LSJ9 s.v.), which can be compared with the noun ὑφάντρου in lines 1 and 11, or ἀντίπ(αις), “a mere boy” (see LSJ9 s.v. II 2), which corresponds to the experts, γέρδιοι, seem reasonable. The total sum of wages for 5 women is 4 drachmas and for the men (their number is uncertain) is 8 dr. and no boys are mentioned regarding this sum. Also, there is no proportion between the number of weavers and the number of ἀντυπ( ). In l. 3 four weavers and 4 ἀντυπ( ), in l. 5 four weavers and 21 ἀντυπ( ) and in l. 7 four weavers and 10 ἀντυπ( ) are recorded. In a letter sent to the strategos Apollonios (P.Giss. I 12, 2–7, A.D. 113–120), an ἰστωνάρχης writes that ἔπεμψάς μοι ὑγιῶς τὸν στήμονα καὶ τὴν κρόκην τῶν φαιλωνίων. παρακαλῶ σε οὖν, τέκνον, ὁσάκις ἐὰν μέ̣λ̣λῃς πέμψαι, ἐντύπην μοι τοιαύτην πέμψον. The noun ἐντύπη was a subject of discussion and it seems that it should be interpreted as a drawing on a papyrus sheet in a scale 1:1, which works as a sample for the reproduction of decorative motifs (“Wirkkartons”)[2]. The striking fact that ἐντύπη and ἀντύπη are found in the context of weaving makes it tempting to assume that ἀντύπη is a variant of ἐντύπη [3]; for the interchange of α and ε at the beginning of a word (in case of an unaccented syllable) see Gignac, Gram. I, 283. The noun ἐντύπη derives from the verb ἐντυπῶ and its meaning is comparable with one of the verbs ἐμπάσσω (see LSJ 9 s.v. “weave rich patterns in a web of cloth”), ἐντίθημι (see Hom. Il. 19,179), ἐνυφαίνω (see LSJ9 s.v. “weave in as a pattern”, “to be inwoven”) or διυφαίνω (see LSJ9 s.v. “fill up by weaving”, “interweave”); cf. also the noun τύπος with the meaning “form, shape” (LSJ9 s.v. VI). With this approach the Michigan papyrus reveals the same noun and our assumption best accords with the present data: the total number of female weavers who worked on the production of garments with a certain number of patterns is seven (l. 8), but the number of male weavers cannot be read with certainty at the end of the line (probably 9). From the preserved names (in ll. 2–7) Agathous and Chairas are two men and Heros, Demetrous, Ekloge and another woman are four women. Therefore, the names of the other three women and, presumably, of some more men (nine, if the reading θ is correct in l. 8) are lost at the left part of the papyrus. The numbers of weavers are even (2 or 4) per line. This might indicate that these weavers were working in pairs[4]. Because of the fragmentary condition of the document it is certain if these teams consisted of a male and a female weaver. Some persons appear more than once in the text, which might mean that these weavers were working in various teams during a certain period. Furthermore, the first account (λόγος) was made one day after the middle of the month Phaophi, and the second was made on the very same day of Choiak, that is, two months later. There is no information about the work in Hathyr, which is the month in between. We cannot say whether the second account extends over a 15-day period in Choiak or over an one-and-half-month period (in Hathyr and half of Choiak).

Then, it is interesting that the number of Wirkkartons varies from 10 to 21 for the same number of weavers (e.g. four weavers in l. 5 and 7), who probably worked on the same number of looms (and garments) at a time. It is obvious that one Wirkkarton was not always sufficient to produce the patterns that the decoration of a specific textile required. Several Wirkkartons were needed for tabulae, various decorative stripes, necklines and so on [5]. Also, there are many ways to weave such patterns in a woven cloth, but all of them require various amounts of time. This interpretation explains why the same number of weavers is recorded with various numbers of patterns. Although a weaver usually tries to follow a standard design, there are always factors, which may lead to some modification: personal initiative, some minor mistakes in counting the threads or various differences concerning the thickness and the strength of the spun threads.

This document raises another question regarding the understanding of the noun ὕφαντρον. The nouns ending in -τρον have always been a subject of discussion, because they present various problems of interpretation when they appear in documents. First, U. Wilcken considered this noun to be “Werkzeug”, “Mittel zur Erreichung von Zwecken”[6], then H.I. Bell concluded that this noun has “an abstract rather than a concrete sense” and denotes fees[7]. Afterwards, B. Olsson translated it as “Lohn” or “Kosten” and concluded that “in diese konnte man natürlich in gewissen Fällen Kosten für Materialien einschliessen” and that “wenn es sich um Werkzeuge handelte, sollte, wohl an irgend einer Stelle der Singular vorkommen. In vielen Fällen scheint mir auch der Preis zu niedrig, als dass man von Werkzeugen sprechen könnte”[8]. E. Wipszycka [9] agrees with this assumption: “la rémunération payée au tisserand par la personne qui lui avait passé une commande portrait le nom de ὕφαντρα ou κέρκιστρα”. Finally, A.E. Hanson in her commentary on ὕφαντρα in SB XVI 12314, 57 (II A.D.), agreed with Bell[10]. Like the noun βάπτρα in l. 16 of SB XVI 12314, which is interpreted as “charges for dyeing”, ὕφαντρα has been translated in the same way, “charges for weaving”[11] . However, the singular ὕφαντρον of the Michigan papyrus is also attested only in PSI VI 599, 8–9 ὕφαντρον τοῦ ἑνὸς ὀθονίου χαλ(κοῦ) (δραχμὰς) γ, a private letter, which dates from the third century B.C.[12]; all the other attestations are in the plural [13]. Since the noun is attested in the singular, as Olsson pointed out (see above), it is not certain whether the noun should be interpreted as “charges (or fee) paid out for weaving” or “cost for weaving equipment” [14]. The assumption that ὕφαντρον was an amount of money spent for some kind of equipment, e.g. threads etc., could be supported by the appearance of the noun στατήρ (ll. 9 and 17), which is probably a measurement for the weight of threads. In P.Ryl. II 127, 27 (A.D. 29) the cost of the threads for the warp and the weft (but the exact quantity is not recorded) to be used for weaving a garment was 18 dr. In P.Oxy. XXXI 2593, 5–12 (II A.D.) 30 staters cost 21 dr. (0.70 dr./stater). Threads for the warp was at 8 dr. (probably 20 dr./stathmion) in P.Mert. III 114 (late II A.D.)[15]. Nevertheless, even though the amounts could fit the interpretation “cost for weaving equipment”, this is also open to doubt. In a short account there was no reason to make a distinction regarding the equipment used by women and men. If the scribe simply writes “for all the cost of weaving in the month, 12 dr.”, it would be adequate. In addition, if the teams comprised both women and men, how they could separate what is the exact cost of each of them? It does not seem probable that someone kept daily records about the amount of equipment that each person needed and then these daily expenses were summed up in a (semi-?)monthly account.

Then, I have refrained from assuming that the money paid out to 5 female weavers (4 dr.) and 9(?) male weavers (8 dr.) (in half(?) month) were wages of

weavers, since we know from other documentary sources that a weaver in the first century A.D. was salaried at c. 17–18 dr./month [16]. On the other hand, if we interpret the noun as charge for weaving and we assume that the lost number

of ἀντυπ( ) at the end of l. 4 was 1–10, then the charges for weaving c. 50 ἀντυπ( ) were 12 dr., that is c. 1.5 obols/

ἀντυπ( ). This amount seems reasonable, if we compare it with the charges for various works concerning cloths (ἤπητρα and κέρκιστρα) in P.Oxy. IV

736 (c. A.D. 1): l. 10 ἤπητρα εἰς φαινόλ(ην) Κοράξου (ὀβολὸς) α (ἥμισυ), l. 77 κέρκισ[τ]ρα φα[ι]νόλ(ου) (δραχμὴ) α̣ (διώβολον).

Equally difficult to explain is the reference in l. 8 to seven and in l. 9 to five female weavers (in l. 10 the number of the male weavers is lost). It is reasonable that only a certain number of male and only 5 out of 7 female weavers were paid. I think that the most realistic inference to be drawn is that these were professional weavers, while the others were assistants or apprentices. Since the amount of threads paid for the work done by women is almost the half of the amount paid to men, one might wonder if the men were professional weavers assisted by women, who perhaps were not present all the time and did less work, especially if they had other obligations (e.g. in their household). Alternatively, since some female names (Ekloge and Demetrous) appear in various teams (Demetrous is mentioned twice with Ekloge, ll. 4 and 6, and once with another woman, l. 7), we might think of the case of a small textile establishment, where the persons have to work in various teams to produce the best results.

Another interest of this document lies in the attestation of the personal name Ekloge, which is for the first time found in Egypt (see comm. to l. 4), and the use of ἄρσην as opposite to γυνή instead of the noun ἀνήρ (see comm. to l. 8). The hand which wrote the account is characteristic because of the regular and well executed letters and the abbreviated words indicated with superscript letters.

[Year x of Tiberius Caesar] Augustus Phaophi 16 account of charge for weaving. [ ] of Agathous and Heros 16th going into [ ] weavers 2, patterns 4. [ ] Demetrous and Ekloge, weavers 4, patterns [ ]. [ ] Chairas and Demetrous, weavers 4, patterns 21. [ ] Demetrous and Ekloge, patterns 5. [ ] Demetrous and another woman, weavers 4, patterns 10. [ ] women weavers 7 and men [ ] of the stater women weavers 5, total of the account of women 4 silver drachmas. [ ] of the men weavers 8 silver drachmas, total 12 silver drachmas …

[Year x of Tiberius Caesar] Augustus Choiak 16 account of charge for weaving. [ ] Serapion … and Mitos son of Ta[ ] patterns 10 [ ] patterns 12 [ ] patterns 6 [ ] patterns 15 [ ] of the stater weavers [ ].

1. Φαῶφι ις: October 13 or 14. Certainly the year should be after the 20th year of Tiberius (A.D. 33–34), the year stated on the recto. R.S. Bagnall in the article Notes on Egyptian Census Declarations II, BASP 28 (1991) 31, n. 16, argues that the declaration on the front side should be dated presumably to A.D. 35, rather than A.D. 33/34 “since the Arsinoite declarations were normally filed in the second half of the year following that of the census” (see BL X 205). Therefore, the only possible October and December (see below l. 11) to which our account should be dated are of A.D. 35 (22nd year of Tiberius) or 36 (23rd year of Tiberius; Tiberius died in March 16, A.D. 37).

2. Ἀ]γ̣αθοῦτο(ς): The reading Σαμ]β̣αθοῦτος is not possible. The personal name Agathous is attested in the Roman period (e.g. P.Mich. V 326, 17 [A.D. 48]; P.Oxy. XIV 1710 [A.D. 148]; P.Mil.Vogl. I 28, 6. 8. 19 [A.D. 163]; P.Oslo II 52, 21 [II A.D.]; P.Oxy.Hels. 22, 7 [II–III A.D.]) and its appearance in our papyrus seems to be the earliest one.

Ἡρῶτο(ς): The feminine name Heros is attested in the Roman period (with most examples in the second century A.D.) in the Arsinoite nome. Naturally, therefore, the thought arises that the papyrus was reused in the same nome.

ις εἰσπορευωντ ̣: Below τ there is ink and it seems that the scribe squeezed the letters at the end of the line: A tolerable reading could be α̣ι̣ or ω̣ν̣, but the spelling of εἰσπορεύωνται (l. εἰσπορεύονται) or εἰσπορευώντων (l. εἰσπορευόντων) is wrong. The verb εἰσπορεύω is usually expected in the passive voice (see LSJ9 s.v. and SB XX 14656, 16; SB XVI 12818, 5; P.Cair.Zen. I 59015, 18; P.Col. III 6, 10; BGU VI 1463, 7; P.Col. IV 81, 14–15 (Ptolemaic period); P.Oxy. IV 744, 4–5 (1 B.C.) and P.Oxy. IV 717, 5, 7 (end of the first century A.D.). For the syntax cf. P.Giss.Apoll. 9 (A.D. 115) πα[ρ]ά τινων ἀπὸ Ἰβιῶ̣ν̣ος σή̣μερον ἐ̣λθόντω[ν. The relationship of the 16 th with the preceding Phaophi 16 is not clear. I am not sure if and how the construction should continue in the next line.

4. Ἐγγλογή: The personal name is attested in various areas of the ancient world; see LGPN I; IIIa; Va. For the interchange of κ and γ before another consonant see Gignac, Gram. I, 79. Here we have a gemination of γ, as well; cf. UPZ I 14, 41, 90 (157 B.C.); SPP XX 9, 27 (A.D. 157–161).

γέρδ(ιοι): The resolution of the abbreviation is γέρδ(ιοι), but since the persons might be all women we could also resolve the feminine form γερδ(ίαιναι), which appears in the Greek papyri of the Roman and Byzantine period, but not γερδ(ίαι), which is rarely attested in Byzantine sources (see LSJ9 s.v. γερδία citing Edict. Diocl. 20.12; Suda s.v. γέρδιος); for the attestations in the first century A.D. in the Arsinoite nome see F. Ippolito, I tessitori del Fayyum in epoca greca e romana: le testimonianze papiracee, in: PapCongr. XXII, 701–715, esp. 708; also for weavers see K. Droß-Krüpe, Wolle (above n. 2), 58–86.

6. The number of ἀντυπ( ) at the end of line is either ε̣ (5) or κ̣ (20).

8. γυναῖκες γέρδ(ιοι) ζ καὶ ἄρσενε̣ς̣ ̣: The use of the adjective ἄρσενες instead of the noun ἄνδρες as a pair of the noun γυναῖκες is noticeable; cf. a parallel in P.Sijp. 44, 7–8 (c. A.D. 130) τινα τ̣ῶ̣ν̣ ἀρσέν\ω/(ν) [υ]ἱῶν̣ … ἐ̣[ὰν] δ̣ὲ τῶ̣ν θυγατέρων. For ἄρσην in papyri usually modifying animals (and not persons, unless they are children or slaves, υἱός, δουλάριον etc.) see Z.M. Packman, Masculine and Feminine: Use of the Adjectives in the Documentary Papyri, BASP 25 (1988) 137–148, esp. 145.

The number at the end seems to be θ̣; cf. the same form of the letter in l. 2 Ἀ]γ̣αθοῦτο(ς).

9. and 17. το]ῦ στατῆρο(ς): The stater was an accepted and standard measurement of products used in weaving (e.g. κρόκη and στήμων); see the discussion in Fr. Mitthof, Das Wertverhältnis des alexandrinischen Billon-Tetradrachmons zur Reichswährung unter Augustus und Tiberius, Chiron 39 (2009) 193–207, esp. 201, 4 n. The lost part at the beginnings of both lines (9 and 17) is an obstacle to the interpretation of the text and the relation of the stater to the amount of 4 drachmas (ἀργυ(ρίου) (δραχμὰς) δ) in l. 9.

At the end of line 9 after δ some traces of ink are probably offsets.

10. 12 dr. is the sum of 4 dr. (for female weavers, l. 9) + 8 dr. (for male weavers, l. 10). At the end of the line after the total sum of 12 dr. there are traces of ink of c. 4 letters.

11. Χοίακ ις: December 12 or 13.

12. Μ ̣ ν̣ο̣( ) καὶ Mίτου Τα ̣: Μ ̣ ν̣ο̣( ) is probably the name of the father of Serapion. The second letter seems to be an η, and we could read Μηνο(δότου) or Μηνο(δώρου). As for Μίτου, the genitive of the noun μίτος “thread of the warp” (see LSJ9 s.v.), even though it is an attractive interpretation in the context of the papyrus, I do not see how this meaning can make sense here. The last letter of the line is probably υ̣ and the second person was probably Mitos, son of Tau(?)[ ]. The personal name Mitos is not attested in Egypt so far, but it is found elsewhere; see LGPN IIIb and IV s.v.

- - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - -

Workshop of Papyrology and Epigraphy

|

Nikos Litinas |

[1] The papyrus is published and the image is digitally reproduced with the permission of the Papyrology Collection, Graduate Library, University of Michigan. For an image of the papyrus see http://quod.lib.umich.edu/a/apis/thumb/2/4/v/124v.jpg (November 6, 2013). I am grateful to Kerstin Droß-Krüpe: my discussions with her on various issues concerning the interpretation of this document were very fruitful.

[2] See LSJ9 s.v. II “pattern”; M. Kortus, P.Giss.Apoll. 20 = P.Giss. 2, comm. to l. 6: “ἐντύπην ist hier als Bezeichnung für ein Gewebemuster (Preisigke, Wörterbuch I, 503) oder für ein Warenzeichen (E. Kornemann, P.Giss. III, 161) gebraucht”; For the meaning “Wirkkarton”, a drawing on a papyrus sheet in a scale 1:1, which works as a sample for the weaver to reproduce decorative motifs see A. Stauffer, Antike Musterblätter. Wirkkartons aus dem spätantiken und frühbyzantinischen Ägypten, Wiesbaden 2008, esp. 14–16, where two instances in the Greek papyri are discussed: also P.Wisc. II 38, 114 (A.D. 54–76) χά̣ρτου ἐντυπ( ). Cf. K. Droß-Krüpe, Wolle – Weber – Wirtschaft. Textilproduktion der römischen Kaiserzeit im Spiegel der papyrologischen Überlieferungen (Philippika 46), Wiesbaden 2011, 158–159; in addition, see C. Nauerth, Zu Wirkkartons in den Papyri, ZPE 168 (2009) 278, for eventual attestation of Wirkkartons in O.Claud. II 239, 3–5 (mid-II A.D.) and P.Tebt. II 414, 12 (II A.D.). Finally, the noun παράδειγμα (see Stauffer, op. cit., 15, n. 44) is found with the meaning “pattern” in the context of mummification. We may compare the fact that in medieval and modern Greek the noun ξόμπλι, which derives from the Latin exemplum, is used for the decorative motif woven in a cloth.

In both the Michigan and the Gissen papyrus the noun ἐντύπη cannot be interpreted as a sample of textile/fabric or of a specific garment or a motif woven in a small piece of cloth as sample (in Greek ξομπλοπάνι and it seems a medieval practice) or a motif traced on a piece of paper (which is a modern practice).

[3] Also, it is not probable that the form ἀντυπ( ) comes from ἀν<τί>τυπον (or ἀντιτύπωσις in LSJ9 s.v. “an image impressed”), an haplography which finds a parallel in the ἀν<τί>τιτος – ἄντιτος (see LSJ9 s.v.).

[4] As experimental archaeology has shown, teams of two weavers work faster and more efficiently; see Droß-Krüpe, Wolle (above n. 2), 82, n. 108 and 109.

[5] Cf. e.g. Stauffer, Antike Musterblätter (above n. 2), the tunic at Farbtafel 5c.

[6] See Zu den Leipziger Papyri, APF 4 (1908) 484.

[7] See The “Thyestes” of Sophocles and an Egyptian Scriptorium, Aegyptus 2 (1921) 281–288, esp. 283–286.

[8] See Die Substantiva auf -τρον in den Papyri, Aegyptus 6 (1925) 289–293.

[9] See L’industrie textile dans l’Égypte romaine, Wrocław 1965, 56 and 75.

[10] P. Mich. inv. 1933: Accounts of a Textile Establishment , BASP 16 (1979) 75–83, esp. 81, comm. to l. 16 (citing also Palmer, Gram., 117).

[11] See ed. pr. by Hanson, P. Mich. inv. 1933 (above n. 10).

[12] In SB XVIII 13766, the reading in l. 15 [ὑ]φάνδρ[ο]υ̣ is quite uncertain and (based on photo) I think we should read [ὕ]φανδρα̣; cf. the final α in the nominatives βάψιμα and ἔρια in ll. 13–14). In l. 18 [ὑ]φανθρ( ) is abbreviated and could be also resolved in the plural.

[13] P.Enteux . 4, 4 (219–218 B.C.), a petition; P.Lond. III 1168 introd. (p. 136) (A.D. 43–44); SB XX 14526, 15 (A.D. 57), an account, ὑπὲρ ὑφάντρω(ν) (δραχμαὶ) ε; P.Mich. III 201, 12 (A.D. 99), a private letter; P.Gron. 11, 6 ὑφάντρων χιτῶνος (δραχμαὶ) κ (ὀβολοὶ) κ; SB XVI 12314, 57 τεισμῆς ὑφάντρων (δραχμαὶ) πδ (both of II A.D.), and SB XVIII 13766, 15, 18 (II–III A.D.), as corrected above (n. 12).

[14] Cf. the same discussion of this difficulty concerning γράπτρα in Bell, The “Thyestes” (above n. 7). Certainly ὕφαντρον is different than δαπάνη as it is clear in SB XVIII 13766, 15–16 [ὑ]φάνδρ[ο]υ̣ (δραχμαὶ) λβ. δ̣απάνης γερδ(ίου) (δραχμαὶ) δ “weaver drachmas 32; expenditure of the weaver drachmas 4” (see P.J. Sijpesteijn in ed. pr. of this papyrus Six Papyri from the Michigan Collection, Tyche 1 [1986] 184–186); cf. also P.Oxy. IV 736, 27 ζύτου γ[ε]ρδί(ου) (διώβολον); l. 35 ἀρίστῳ [γε]ρ̣[δί(ου)] (ὀβολός); l. 37 τὸ περι̣δ[ι]πνο( ) Ἀθη( ) γναφέω(ς) (ἡμιωβέλιον).

[15] See Wipszycka, L’industrie textile (above n. 9), 75–76 concerning the provision of the raw material by the weaver or the person who ordered the garments.

[16] For the wages see also Droß-Krüpe, Wolle (above n. 2), 207–214.