María Limón Belén

Towards a New Interpretation of CLE 2288 through its ordinatio*

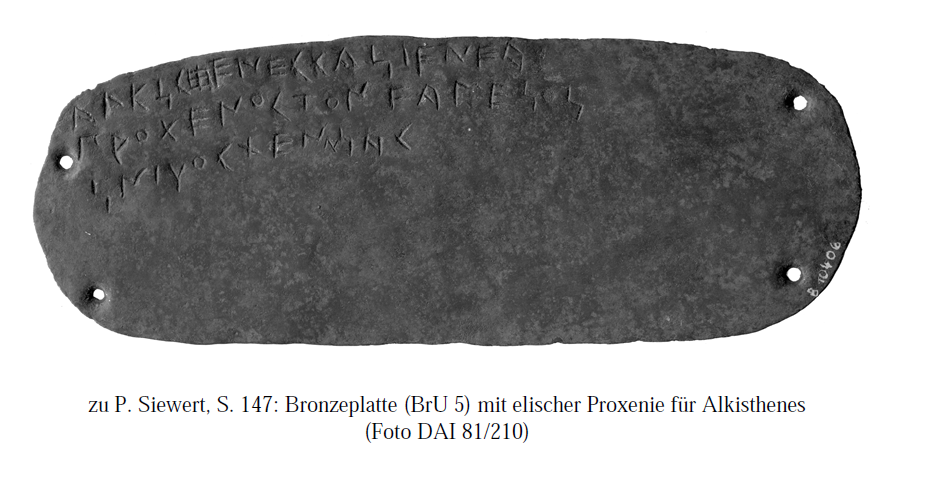

Tafeln 7–8

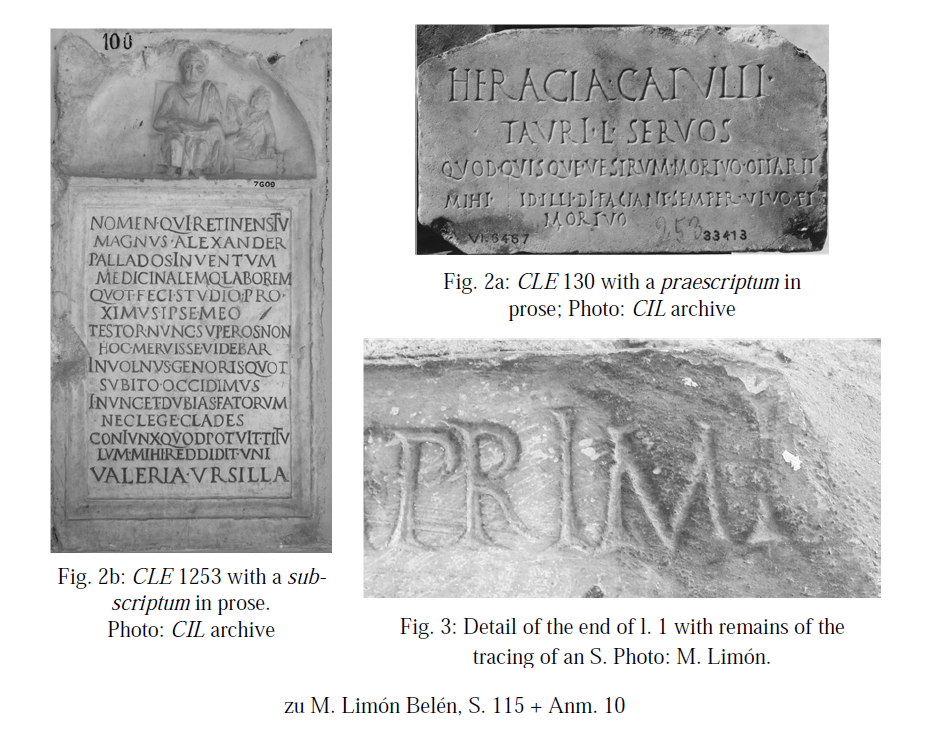

The ordinatio, usually understood as a manual task involved in the production of ancient epigraphs, has repeatedly been studied in detail over the last few decades[1]. However, in this paper the term ordinatio refers to the external distribution or layout of an epigraph. The study of the ordinatio in the latter sense applied to the Latin verse inscriptions is a relatively recent and novel approach. It was first developed by J. del Hoyo in a study of epigraphic carmina from Hispania[2]. It is now well-known that the layout of much of the Carmina Latina Epigraphica[3] was established using tactics and resources with two basic purposes: distinguishing and separating verse from prose, and providing some help to avoid problems when reading the carmen[4]. Therefore, marks for separating verse from prose or to show verse boundary can be found in many of these inscriptions. Recent scholarship has shown that a good knowledge of these features enables us to reconsider earlier editions of theCLE, as in the case of CLE 2288, but also to recognize new carmina from fragments of inscriptions[5] and to identify CLE inscriptions previously published as prose [6].

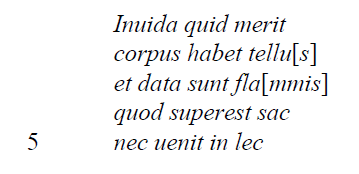

CLE 2288 is a clear example of the ordinatio being a significant factor when editing verse inscriptions (see fig. 1). This inscription is preserved at the church of S. Silvestro in capite at Rome. As many other churches in this city, S. Silvestro houses dozens of ancient Latin epigraphs embedded in the walls of its courtyard which isolates the entrance of the church from the street. According to Paolino Mingazzini [7], this collection was acquired by Rev. Whitmee between 1900 and 1910. Mingazzini thinks it is possible that most of the texts originate from the necropolis of the via Salaria which was repeatedly plundered between 1904 and 1910.

CLE 2288 is fixed on the left-hand side of the hallway leading to the patio where I saw and photographed it in April 2013. It is a small marble tablet measuring (14) × (16) cm, nowadays covered with a thin coat of ochre paint, the same colour as the wall (see fig. 1). It is broken into three pieces, having lost its right half. The lower left-hand corner is also damaged but this does not affect the text. It is engraved in capital book script with a good deep cutting measuring 1 cm on average (lines 1–6), and 1.4 cm (line 7). After each word there are triangular interpunctions with the vertices pointing downwards. Lines 2, 4, 6 and 7 are indented. It can be dated in the first or second century AD according to its palaeography.

P. Mingazzini[8] first published it together with other inscriptions from the same church. It must be noted that this edition does not respect the indentation of the original text:

This edition indents the first and last line, and aligns the others, which the author must have considered as part of the carmen, although this is not stated. Neither is the metrical scheme of the text specified which, in his opinion, could be composed in hexametres or elegiac couplets. P. Mingazzini does not state whether he regards any line of the text as written in prose.

On the other hand, Ernst Lommatzsch includes this inscription among the fragmenta in his collection of Carmina Latina Epigraphica under the number 2288[9]. He reproduces the text from the edition by Mingazzini making no changes and indicating nothing about the metre. Regarding the layout of the text, Lommatzsch does not include the indentation of the even lines, which shows that he has neither seen the inscription nor corroborated Mingazzini’s edition. In his collection this text appears as:

In the critical apparatus the author adds that the name Beryllum Primi ... appears first and is followed at the end by that of Clodia ... , both in prose, as far as he deduced. The carmen would therefore begin with Invida quid […].

I propose a new interpretation of which lines are in prose, and which ones are in verse; questions regarding the metrical scheme will be tackled at a later stage.

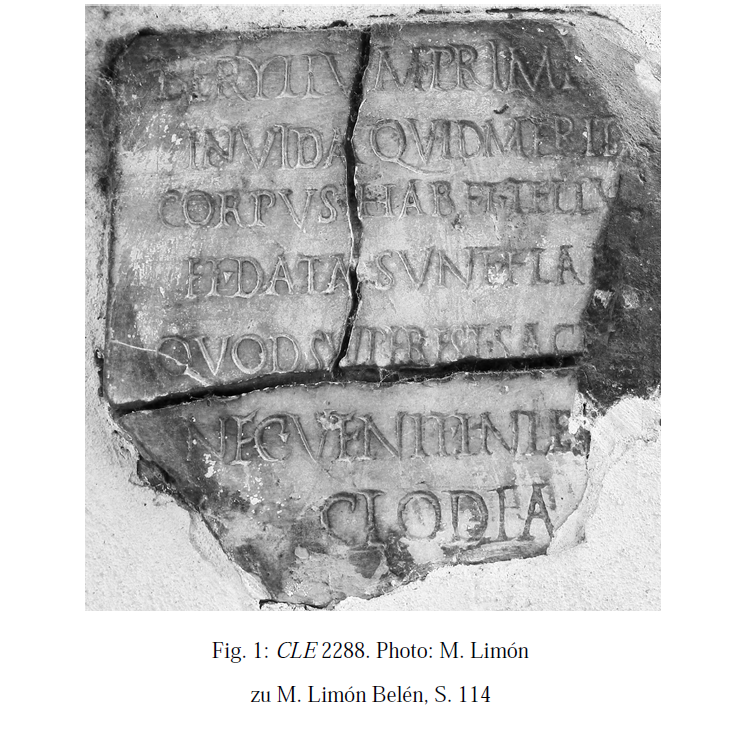

First, I would like to focus on Beryllum primiṣ[10] [---], or rather, what remains of the first line. When analysing the ordinatio of the CLE, it has often been shown that the text in prose has a larger font size than the text in verse[11]. Thus prose can be distinguished from verse almost at first sight. Two of many hundred examples, also from Rome, are CLE 130 and CLE 1253 (see fig. 2a and b).

It must be noticed that the text of the first line is inscribed in the same font size as the rest of the lines in verse (1 cm on average). However, Clodia has a greater indentation (perhaps the entire line was originally centred), and is slightly larger in size than the other lines (1.4 cm). For this reason, line 7 must be certainly understood as a subscriptum in prose. By contrast the sequence Beryllum primiṣ [---] in the first line has the same lettering size as the remaining lines of the carmen and fits faultlessly into the scheme of a hexametre. In addition, the restoration of the form primis precludes the possibility of a nomen in prose as provided by Heikki Solin [12]. Hence, the first line must be considered as verse.

Second, as can be seen in the photograph (see fig. 1), the even-numbered lines of the text are indented. This is a significant fact that makes me turn now to the metrical scheme.

According to Mingazzini the inscription appears to be in hexametres or in distichs. Both options could be possible, at least initially, since all the lines could fit into those two schemes. The problem is that if we accept that the carmen is in distichs and we consider the first line of text — that of Beryllum primiṣ — to be prose[13], this means that the hexameters, the odd-numbered lines, are indented. However, the norm for epigraphic distichs is to indent even-numbered verses, the pentametres[14]. Besides, if these are distichs and the first line is considered to be prose, there is a verse missing to complete the third distich.

It has been shown that the ordinatio provides some indications to suggest that the first line is not a praescriptum in prose, but another line of verse. At this point, it also enables us to confirm that the remaining verses are elegiac distichs and that there is verse-line coincidence.

The addition of the first line as another verse results in three complete distichs. With the addition of this line, the indentation of the even-numbered lines coincides with the pentametres, as has been shown to happen regularly in this type of composition. The carmen is no longer uneven and the formal composition of the inscription is more balanced and harmonious.

Considering all the above-mentioned statements, I propose the following text:

Due to the fragmentary condition of the text, it is difficult to suggest a translation. Nevertheless, the remainder of the carmen contains themes typically found in funerary epigraphic poetry which make it possible to attempt to reconstruct its content even though half of the text is lost[15].

Presumably the deceased was Beryllus. This is a Greek nomen[16] that is documented in a few Latin inscriptions (also fem. Berylla), which are mostly of slaves and freedmen[17]. The inscription may have been dedicated by Clodia whose name is given in the subscriptum. From the content of the sixth verse (nec uenit in lec[tum?] [18]) we might suppose that Beryllus and Clodia were husband and wife. Bearing this in mind, it is more likely that Beryllus was a freedman.

The carmen begins with a mention of the deceased in the accusative (Beryllum). Inuida, in the second verse, requires a subject like mors or fata[19]. Both terms are often used with inuida in the CLE [20]. Sporadically, Parca or Clotho is also documented with the same adjective, always referring to the idea of envious and cruel death that ravishes someone’s life[21]. The idea of someone unfairly snatched by death — Beryllus, in this case — is expressed in the CLE with rapuit, tulit and derivatives[22]. Closely related to the idea of a loved one taken away by death is the topic of mors immatura[23]. Perhaps primiṣ, in the first verse, might point in that direction and we could think of a construction like primis annis for expressing the idea of Beryllus dying prematurely, while he was still a young man[24].

The sequence quid merit[o] (or merit[is]) reminds us of an interrogative formula conveying the interrogatio and criminatio topics, which are usually used to enquire and to blame Destiny, Fortune or the Parcae, for someone’s loss [25].

The three following verses express the contrast between the deceased’s tunc et nunc, now that he has come to bones and ashes [26] (quod superest[27]). The first hemistich of the third verse (habet corpus tellus) is documented in other carmina exactly in the same form [28], or with slight variations[29]. Many of these instances express the contrast between the material side of the deceased (the body lying in the tomb) and the spiritual part (the anima) which is blowing in the wind. In the next line — et data sunt fla[mmis] — the word ossa might be expected, as an image of the bones that have been consumed by the fire[30].

The sequence sac[---] might be related to the family of sacer. It is difficult to say, but perhaps it could be reconstructed as an adjective as sacrum/sacratum matching with quod superest, or a verbal form like sacrauit. In both cases the thought of the remains of the deceased as something sacred[31] and inviolable[32], or the action of consecrating those remains and the tomb where they are buried [33] is present. It also could be recalling the topic of finding comfort for someone’s death in the funerary monument[34].

Finally, nec venit in lectum implies the idea of Clodia, the wife, bitterly regretting because her husband is never coming back to the conjugal bed.

- - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - -

Universidad de Sevilla |

María Limón Belén |

* This work has been undertaken in the framework of the Spanish PAIDI Group HUM-156 and the Project “Inscripciones latinas en verso de Hispania: Tratamientos multimedia para la investigación y su transferencia ( FFI2009-10484)”. I would also like to thank M. Deodati for his help in Rome.

[1] Well-known studies on this issue are, for instance, J. Mallon, Paléographie romaine, Madrid 1952; G. C. Susini,Il lapicida romano, Roma 1968; J. S. and A. E Gordon, Contributions to the palaeography of Latin inscriptions, Milan 21977.

[2] J. del Hoyo, La ordinatio en los CLE Hispaniae, in: J. del Hoyo, J. Gómez Pallarès (edd.), Asta ac Pellege, 50 años de la publicación de Inscripciones Hispanas en verso de S. Mariner, Madrid 2002, 143–162.

[3] Here in after CLE.

[4] M. Limón Belén, La ordinatio en los Carmina Latina Epigraphica de la Bética y la Tarraconense, Epigraphica 73 (2011) 147–160. Other studies on the ordinatio of CLE are: del Hoyo, La ordinatio (above n. 2 ) 143–162; J. Gómez Pallarès, Carmina Latina Epigraphica de la Hispania republicana: un análisis desde la ordinatio, in: P. Kruschwitz (ed.), Die metrischen Inschriften der römischen Republik, Berlin, New York 2007, 223–240; M. Limón, La ordinatio en los CLE de la Provincia Lusitana, in: R. Carande Herrero, D. López-Cañete Quiles (edd.), Pro tantis redditur. Homenaje a Juan Gil en Sevilla, Sevilla 2011, 227–234. The layout of Pompeian verse graffiti and the CLE from Rome have also been studied: P. Kruschwitz, Patterns of Text Layout in Pompeian Verse Inscriptions, SPhV 11 (2008) 225–264; M. Limón Belén, La ordinatio en los CLE de Roma, Diss. Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla 2013 (unpublished).

[5] J. del Hoyo, M. Limón Belén, CLE en el claustro de S. Lorenzo extramuros (Roma), in: C. Fernández Martínez et al. (edd.), Ex officina: literatura epigráfica en verso; homenaje a Xavier Gómez Font, Sevilla 2013, 184–201, nº 1.

[6] J. del Hoyo, R. Carande, Nuevo carmen epigraphicum procedente de Turris Libisonis (Sardinia), Epigraphica 71 (2009) 161–172.

[7] P. Mingazzini, Iscrizioni di S. Silvestro in Capite, BCAR 51 (1923) 63.

[8] Mingazzini, op. cit. 85.

[9] E. Lommatzsch, Carmina Latina Epigraphica, Supplementum II, 2, Leipzig 1926.

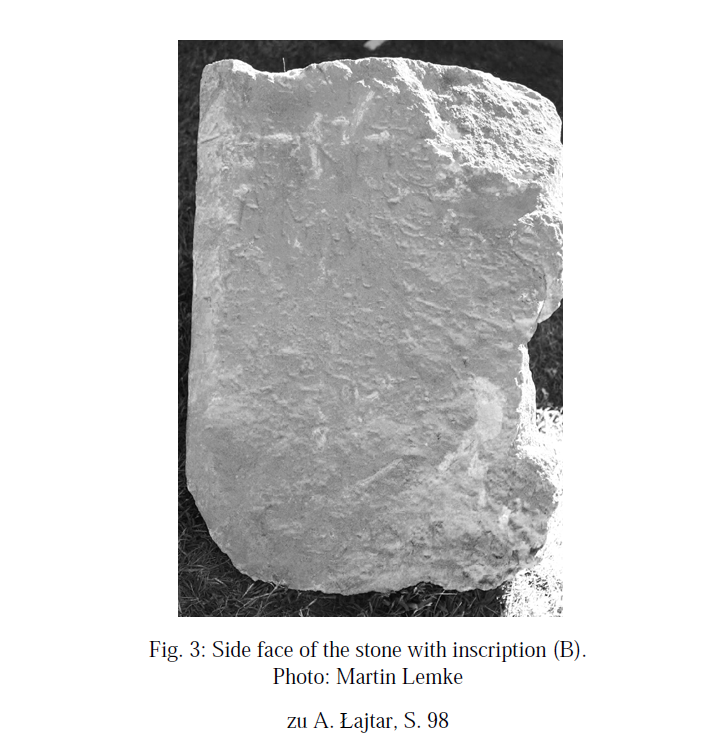

[10] Here I print primiṣ, as I was able to see that the remains of a letter that appears to be an S are still preserved (see fig. 3). Also the latex impression faithful to the original and sent to the CIL at Berlin by B. E. Thomasson (with reference number h6, EC0000020) leaves no doubt.

[11] del Hoyo, La ordinatio (above n. 2) 158–159; Limón Belén, Ordinatio CLE Bética (above n. 4) 152.

[12] H. Solin, Die griechischen Personennamen in Rom: ein Namenbuch, Berlin 22003, 1221. Solin quotes the text edited by Mingazzini.

[13] As proposed by Mingazzini and accepted by Lommatzsch.

[14] del Hoyo, La ordinatio (above n. 2) 154–156; Limón Belén, Ordinatio CLE Bética (above n. 4) 154.

[15] Well-known studies on the themes found in the CLE are B. Lier, Topica carminum sepulcralium latinorum I–II, Philologus 62 (1903) 445–477, 563–603, and III, Philologus 63 (1904) 54–64; J. A. Tolman,A study on the sepulchral inscriptions in Buecheler’s Carmina Epigraphica Latina, Chicago 1910;E. Galletier, Étude sur la poésie funéraire romaine d’aprés les inscriptions, Paris 1922; R. Lattimore,Themes in Greek and Latin Epitaphs, Urbana (Illinois) 1942; and R. Hernández Pérez, Poesía latina sepulcral de la Hispania romana: estudio de los tópicos y sus formulaciones, Valencia 2001.

[16] See Βήρυλλος in P. M. Fraser, E. Matthews, A Lexicon of Greek Personal Names, Oxford 1987–ff.

[17] Solin, Personennamen (above n. 12) 1220 and id., Die stadtrömischen Sklavennamen: ein Namenbuck, Stuttgart 1996, 532.

[18] There are no exact parallels for this expression in the CLE or in the literature. Nevertheless, nec venit in mentem is documented in the same position of the verse in Verg. Aen. 4.39. Lectus is used in other CLE with the sense of conjugal bed (see CLE 2167).

[19] About deities held responsible for death see Lier, Topica I (above n. 15) §14; Lattimore, Themes (above n. 15) §§35–37; Hernández, Poesía (above n. 15) §§34–47.

[20] Tolman, Study (above n. 15) 37–39. For the parallelisms in the CLE that will be cited here see P. Colafrancesco, M. Massaro, Concordanze dei Carmina Latina Epigraphica, Bari 1986.

[21] Lier, Topica I (above n. 15) §5.

[22] Tolman, Study (above n. 15) 34–37; Hernández, Poesía (above n. 15) §24.

[23] Lier, Topica I (above n. 15) §§1–2; Tolman, Study (above n. 15) 29–30. An illustrative example containing the whole idea of a young person caught up by devious and jealous death could be CLE 555: huic aetas prim(is) cum florebat in annis, invida fatorum genesis mihi sustulit.

[24] The use of primis annis or similar terms in the CLE is not exclusive of epitaphs for children: see CLE 555, dedicated to Aurelia Marcellina, a married woman who died in the flower of youth (primis cum florebat in annis); and CLE 667 dedicated to Concordius who died when he was 32 years old but was considered to be still in the prime of his life ( teneris in annis).

[25] CLE 984: Quid tua commemorem, nimium crudelis, iniqua, fletus et casus quid facis inmeriteis?; For further information about these topics see Lier, Topica I (above n. 15) §6; Lattimore, Themes (above n. 15) §47; Hernández, Poesía (above n. 15) §§35–36.

[26] Lattimore, Themes (above n. 15) §45; Hernández, Poesía (above n. 15) §§48–52. A beautiful example containing this idea is CLE 1111: … gratus eram populo quondam notusque favore nunc sum defleti parva favilla rogi.

[27] See, for instance, CLE 1247: … quod superest homini requiescunt dulciter ossa; other examples are CLE 546, 9; and 1111, 14.

[28] CLE 611, 5; 1845, 4; and ICVR VII 20919, 3.

[29] CLE 1206, 10; and 1207, 2–5.

[30] With parallels in CLE 1149, 12–13 and 1252, 7–8.

[31] CLE 834: Ossa piia cineresque sacri hic ecce quiescunt; see also CLE 609, 2–9.

[32] CLE 1021: sacratam cunctis sedem ne laede uiator.

[33] CLE 213: Iuenis Sereni triste cernitis marmor, pater supremis quod sacrauit ...; other parallels are CLE 607, 3; 1036, 4; and 1129, 9–12.

[34] Hernández, Poesía (above n. 15) §§129–137.