Lincoln H. Blumell

A Second-Century AD Letter of Introduction

in the Washington State University Collection1

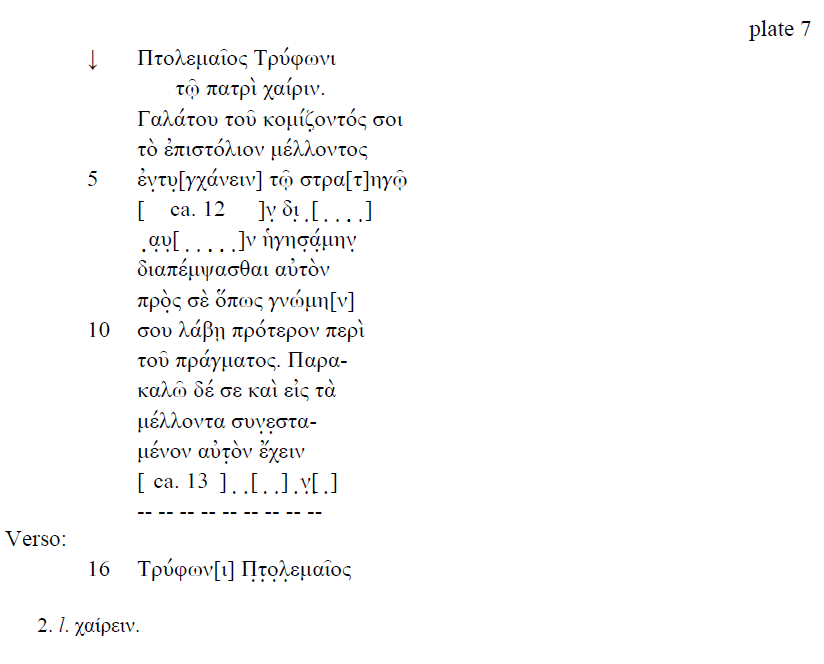

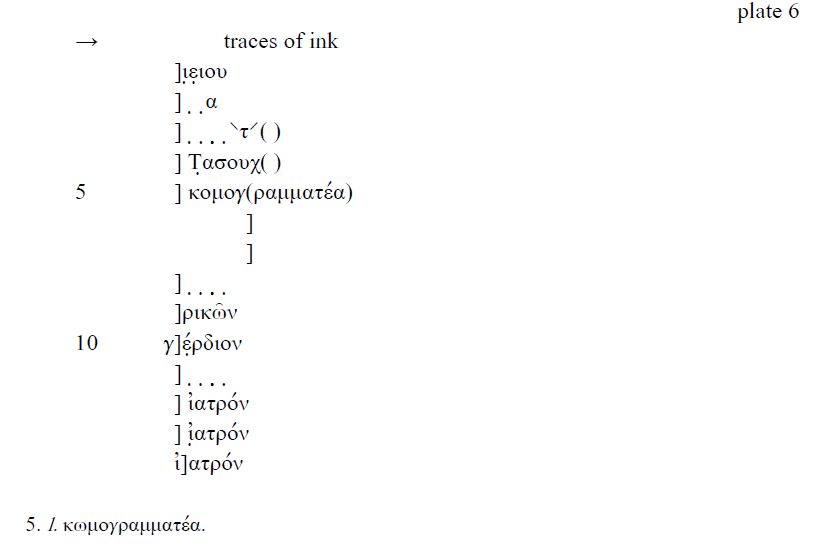

Tafel 6–7

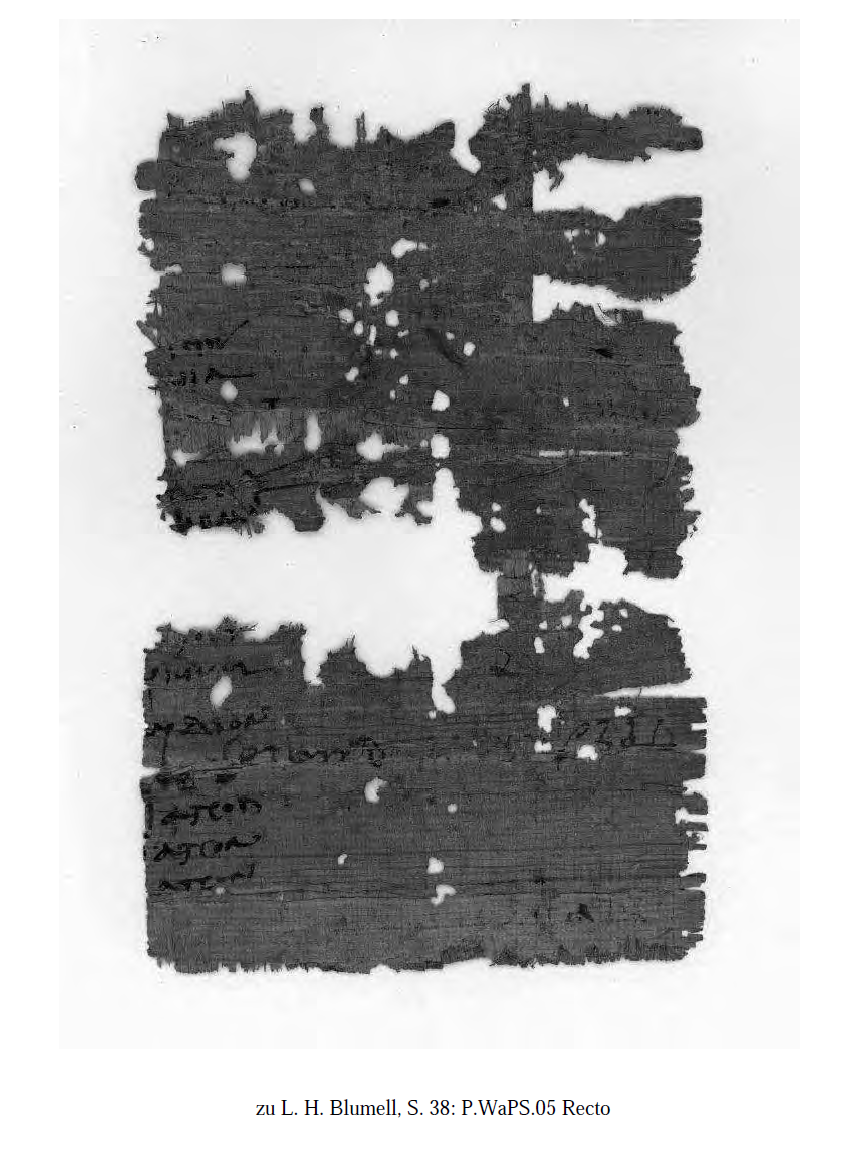

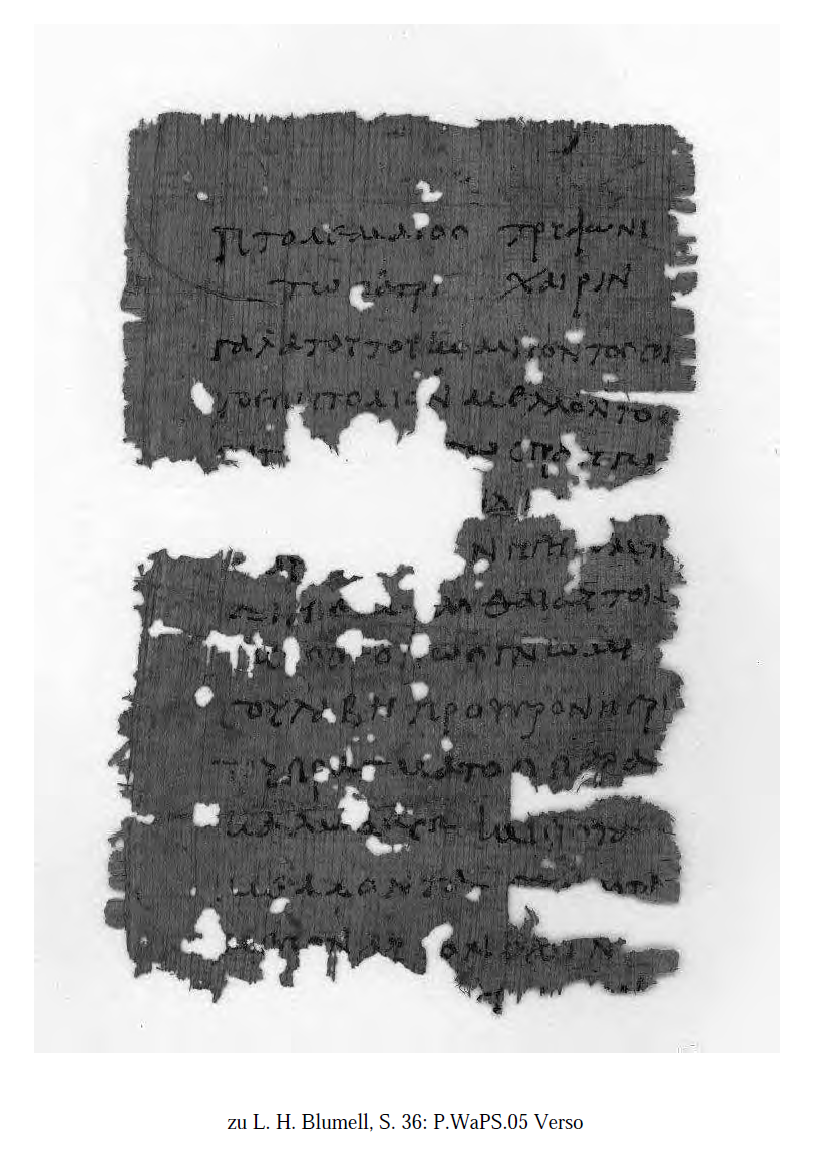

Recently the papyrological holdings of the Manuscripts, Archives & Special Collections Library at Washington State University (WSU) was added to the APIS database.[2] The small collection comprises eight documents, seven written in Greek and one in Arabic, that span from the second century BC to the eighth century AD. The collection was acquired in the early 1970s when Earle Connette, head Librarian of the Manuscripts-Archives Division at WSU, arranged for the purchase of these fragments through Alan E. Samuel. [3] The largest piece in this collection is a rectangular papyrus that measures 13.3 cm (H) by 8.5 cm (W) and carries the inventory number P.WaPS.05.

While there is writing on both sides of the papyrus, the verso has a much larger section of writing than the recto and contains the fragmentary remains of a letter. It therefore seems that the letter was written on a reused scrap cut specially for the purpose since the left and right margins of the text are fully preserved and run up against the vertical edges of the papyrus whereas much of the writing on the recto is lost owing to the cut of the left margin (= right margin on the verso).[4] The beginning of the letter is preserved but it breaks off at the bottom after fourteen lines. Though the hand of the letter (verso) is in some ways similar to the hand on the recto, they are definitely two different hands, and the general similarities can probably best be explained by virtue of the fact that they were written about the same period. The hand of the letter is consistent and clear and overall the orthography is regular. The text shares a number of paleographic affinities with the following papyri, all of which have a second century date: P.Oxy. XIV 1758 (AD II); P.Oxy. XLI 2980 (AD II); and P.Oxy. XLVII 3337 (ca. AD 142).

In this letter the sender, a certain Ptolemaios, writes to his father Tryphon to inform him that a man named Galates is bringing a letter to him and that Galates then intends to meet with the strategus. Before the letter breaks off Ptolemaios requests that his father kindly receive Galates. Despite the seemingly informal structure and familiar background of the letter it essentially functions as a kind of letter of introduction as it contains certain epistolary tropes and formula that are typical in this genre of letters.[5] As Clinton W. Keyes and Chan-Hie Kim have noted, immediately after the opening salutation (A [nom.] to B [dat.] χαίρειν), it is common in letters of introduction for the sender to preface the actual request for commendation by first pointing out to the addressee that the person being commended is bringing the letter. [6] In the present letter this is done in ll. 3–4: Γαλάτου τοῦ κομίζ̣οντός σοι | τὸ ἐπιστόλιον.[7] Four other letters of introduction preserved in the papyri also contain a very similar phrase immediately after the opening address.[8] Just before the letter breaks off Ptolemaios uses a request formula that is otherwise only employed in letters of introduction as he charges his father to take care of Galates: (ll. 11–14) παρα|καλῶ δέ σε καὶ εἰς τὰ | μέλλοντα συνεστα|μένον αὐτ̣ὸν ἔχειν.[9] Since Ptolemaios informs his father that Galates intends to meet the strategus (l. 5), perhaps the request had something to do with Tryphon putting in a good word to the strategus on behalf of Galates. If such is the case, it could also be supposed that Tryphon is a person of some standing, since he had the ear of the strategus.

Though the letter breaks off at this point it seems probable, given that letters of introduction typically followed a loose pattern, that after the request clause and before the concluding valediction Ptolemaios likely expressed some kind of appreciation to his father Tryphon for helping Galates. [10] Additionally, after the “appreciation clause,” it was not uncommon in some letters of introduction for the sender to reciprocate and inform the addressee that they were willing and ready in turn to help them with anything they might need.[11]

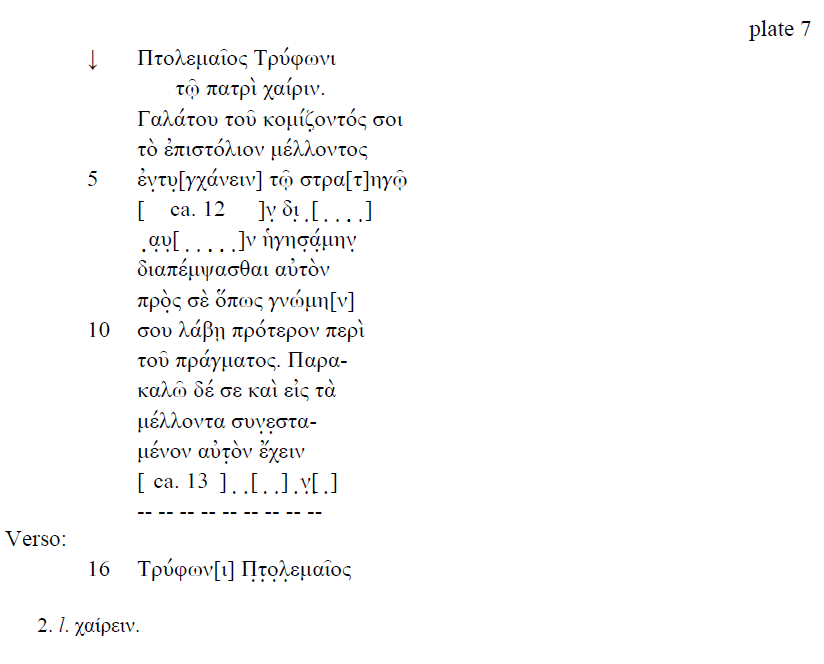

The recto of this papyrus appears to contain the partial remains of one column of a list, where only the last word of the column, typically an occupation, can be read along the left margin, see below (List of Names and Professions). While this papyrus is without provenance, and Samuel’s correspondence with Connette gives no information regarding how or where this papyrus was obtained, there could potentially be one clue within the text that could suggest a likely place of origin. In the fragmentary list on the recto l. 4 reads: Τ̣ασουχ( ). The only possibility is that this is an abbreviation for some woman’s name that begins with Τασουχ-. Female names beginning in this way overwhelmingly come from the Arsinoite Nome. [12] This should come as no surprise since etymologically Τασουχ means “she whom Souchos gave”[13] and as Souchos (Sobek) was one of the most prominent deities in the Arsinoite, theophoric names bearing σουχ are especially prominent in this region.[14] If Arsinoite provenance is correct, given the reference to the meeting with the strategus in l. 5 of the verso, it might be wondered whether the letter was sent to Ptolemais Euergetis, the metropolis of the Arsinoite where the strategus typically resided.

“Ptolemaios to Tryphon his father greeting. Because Galates, who is bringing you this letter, is going to meet the stategus … I thought to send him to you, so that beforehand he should receive your opinion concerning the matter. I ask you to keep him for the future also under your patronance …”

(Verso) “Ptolemaios to Tryphon”.

1–2. While Ptolemaios’ use of πατήρ (l. 2) to identify Tryphon could be metaphorical, like other kinship terms typically employed in letters (i.e. ἀδελφός/ἀδελφή [see E. Dickey, Literal and Extended use of Kinship Terms in Documentary Papyri, Mnemosyne 57 (2004) 1–48]), if he were writing to his literal father then it could be possible that this same Ptolemaios is attested in some other papyri where a “Ptolemaios son of Tryphon” appears: P.Fam. Tebt. 30.11–12 (5 May AD 133, Antinoupolis); P.Oxy. XIV 1692.7–8 (AD 188); SB XII 11028.14 (AD II–III, provenance unknown).

3. Γαλάτου. The nominative form is Γαλάτης and this name typically carries ethnic connotations and suggests some type of Galatian descent. While the name is reasonably well attested in the first three centuries and is confined to no one geographic locus, it is especially well attested in the first and second centuries in the Arsinoite.

4. τὸ ἐπιστόλιον. This refers to the actual letter of introduction that the introductee is carrying, cf. Kim, Greek Letter of Recommendation, 48 (s. n. 5). In P.Giss. I 88.4 (AD 113–120; Thynis) and P.Stras. IV 174.3–4 (late II/early III; provenance unknown) ἐπιστόλιον is similarly used.

5. ἐν̣τυ̣[γχάνειν] τῷ στρα[τ]ηγῷ. Though only the epsilon and tau are clearly visible the reconstruction of ἐντυγχάνειν seems rather certain. If ἐντυγχάνειν is being used in its technical sense it may be wondered if Galates is actually “petitioning” or “applying to” the strategus for some reason.

7. ἡγησ̣ά̣μην̣. Since a nu immediately precedes the verb and the first part of this line is lost in a lacuna it could be possible that the verb being employed is a compound verb, either ἀνηγέομαι or συνηγέομαι. Alternatively, a not uncommon epistolary formula that might be in use here is ἀναγκαῖον ἡγησάμην + infin. “I thought it necessary to ...” The reading of ἀναγκαῖον fits the lacuna rather well and though I have read an α̣υ̣ before the lacuna it could be read as α̣ν̣.

13–14. συνεσταμένον αὐτ̣ὸν ἔχειν. On the use and meaning of this phrase see K. A. Worp, Ἐν συστάσει ἔχειν (note 9) 189–190.

Among the various occupations attested are a village scribe (l. 5, κωμογραμματεύς), a weaver (l. 10, γέρδιος), and three physicians (ll. 12–14, ἰατρός). In l. 9 there could also be a reference to a praktor argyrikon (πράκτωρ ἀργυρικῶν), although owing to the lacuna this reading is not totally certain. Given the very fragmentary nature of the list any suggestion about its contents and purpose must remain tentative. However, one possibility is that it could have contained a list of persons who were being exempted as possible candidates for a liturgy. Physicians were generally except from liturgical service because their profession was deemed an essential service and in the case of the praktor argyrikon and the village scribe they could have been exempted since they were already fulfilling a liturgy and one did not usually perform concurrent liturgies. [15] While there is no evidence that weavers were exempted from liturgical service, the person so identified could perhaps have been exempt for another reason (he was already performing a liturgy) and the title was being employed simply as a means of identifying them.

1. Another possibility is that this line reads ]ι̣σ̣ιου.

3. This line ends with some kind of abbreviation as is evidenced by the superscripted tau, which is the only legible letter on the line.

4. Τασουχ( ). Whatever name is behind this abbreviation, it is a female name. The abbreviation Τασουχ( ) occurs in: P.Gren. II 53d.7 (19 July AD 167; Bachias); BGU IX 1891 vi. 180, vii. 220, viii. 254, ix. 289 (3 Dec. AD 133; Theadelphia); BGU IX 1898 vi.125, 126, vii. 139, 143, xv. 311 (ca. 24 July AD 172; Theadelphia); P.Col. V 51 iv. 94 (ca. 28 Nov. AD 155; Theadelphia). Possibilities include: Τασουχάρειν, Τασουχάριον, Τασουχᾶς, Τασούχιον, Τασοῦχις, Τασοῦχος. If this document does contain a list of persons who were being exempted from a liturgical service the reference to a female is problematic since women were not eligible for the liturgy (Lewis, Exemption from Liturgy, 512–513). Therefore, it may be wondered whether the female name is simply being used as a matronymic to distinguish an ineligible candidate. If such is the case, μητρός probably occurs just before the name in the lacuna.

5. κομογ(ραμματέα). The abbreviation, which is well attested, signifies that the office of a village scribe is being referenced. However, owing to a lack of context one cannot be certain of the case (gen., dat., acc.,), even though I have supplied the accusative, or even if it is a singular or plural.

9. ]ρικῶν. While I suspect that the reading is something like πράκτορα ἀργυ]ρικῶν since other occupations are attested on the list and a search on the DDbDP for ρικων reveals that most often this letter combination appears as part of a reference to a praktor argyrikon there are other possibilities.

12–14. ἰατρόν. The seemingly three separate references to physicians in this list is curious. In BGU XVI 2577 (30 BC–AD 14), a lengthy tax list from Heracleopolis, three doctors are attested but they are spread out over the entire list (ll. 322, 339, 404) and do appear together (cf. P.Yale III 137.44, 133, 185 [AD 216–217; Philadelphia] Account List; SB XXIV 16000.42, 315, 509 [early AD IV; Panopolis] List). Similarly, in P.Ross.Georg. V 57R (AD III), an unprovenanced list of persons in a hospital along with prescriptions, three different doctors are mentioned (ll. 4, 22, 24) but not in succession. Without more context it is difficult to extrapolate much about the doctors since there is no parallel.

- - - - - - - - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - - -- - - - -

Brigham Young University |

Lincoln H. Blumell |

[1] I thank Cheryl Gunselman, Manuscripts Librarian of the Manuscripts, Archives & Special Collections Library at Washington State University, for permission to publish this piece and for permitting me to include images of this papyrus in the present article. I also thank Todd Hickey of UC Berkeley for bringing this text to my attention.

[2] A list of these documents, with images, can be found on the APIS website under ”WSU Pullman.“ The address for this website is: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/projects/digital/ apis/search/.

[3] In a two-page letter dated 13 March 1970, and in possession of the WSU library, Dr. Samuel writes to Connette and describes the contents of the papyri and also outlines various price options for the sale.

[4] For letters written on the back of a recycled papyrus see R. Luiselli, Greek Letters on Papyrus First to Eighth Centuries: A Survey, AS/EA 62, 3 (2008) 686–687; R. S. Bagnall and R. Cribiore, Women’s Letters from Ancient Egypt, 300 BC – AD 800, Ann Arbor 2006, 34–35.

[5] On letters of introduction see: C. W. Keyes, The Greek Letter of Introduction, AJP 56, 1 (1935) 28–44; C.-H. Kim,Form and Structure of the Familiar Greek Letter of Recommendation, Missoula 1972. See also T. Teeter, Christian Letters of Recommendation in the Papyrus Record, P & BR 9, 1 (1990) 59–69; P.Oxy. LVI pp. 111–116 (= P.Oxy. LVI 3857: “Christian Letter of Introduction”); K. Treu, Christliche Empfehlungs-Schemabriefe auf Papyrus, in:Zetesis. Album amicorum, door vrienden en collega’s aangeboden aan E. de Strycker, Antwerpen 1973, 629–636; H. Cotton, Documentary Letters of Recommendation in Latin, Königstein 1981.

[6] Keyes, Greek Letter of Introduction, 39–40; Kim, Greek Letter of Recommendation, 43–47.

[7] Interestingly, in pseudo-Demetrios’ τύποι ἐπιστολικοί, written sometime between 200 BC and AD 200, when he talks about how one writes a “letter of commendation” (ἐπιστολὴ συστατική) he notes that it should begin as follows: τὸν δεῖνα τὸν παρακομίζοντά σοι τὴν ἐπιστολήν … Greek text of pseudo-Demetrios is taken from A. Malherbe, Ancient Epistolary Theorists, Atlanta 1988, 32–33.

[8] P.Cair.Zen. IV 59603.2 (= Keyes no. 19; Kim no. 33): Μν]ησίθεος ὁ κομίζων σοι τ̣[ὴν ἐπιστολήν (III BC; unknown provenance); P.Col. III 7.2 (= P.Zen.Pest. 42; Kim no. 6): Πτολεμαῖος ὁ κομίζων σο̣ι̣ [τὴν ἐπιστολ]ήν (257 BC; Arsinoite); PSI IV 415.4–5 (= SB XXII 15278; Kim no. 37): ὁ κομ̣ί̣ζων \σοι/ τὴν ἐπιστ[ο]λήν (246–45 BC; Philadelphia); P.Oslo II 51.3 (= Kim no. 58): Ἡρᾶς ὁ κομίζων σ̣ο̣ι̣ τ̣ὴ̣ν ἐπιστολ̣ήν (AD II; Arsinoite).

[9] Kim, Greek Letter of Recommendation, 61–71. Kim notes that in the Roman period the request clause typically took one of three forms: 1. καλῶς (ἂν) ποιήσεις + particle expressing action; 2. χαριεῖ μοι + participle expressing desired action; 3. ἐρωτῶ/παρακαλῶ σε ἔχειν αὐτὸν συνισταμένον. The present formula is basically an exact parallel to Kim no. 3. Concerning this formula Kim remarks: “… this third type is found only in the letters of recommendation: the formula clearly uses the verb συνίστημι in the sense of ‘to introduce.’ The function of this formula is slightly different than the other two, in that it expresses nothing more than the intention of the writer to recommend the bearer of the letter strongly.” Cf. K. A. Worp, Ἐν συστάσει ἔχειν = ‘To take care of’, Tyche 15 (2000) 189–190.

[10] Kim, Greek Letter of Recommendation, 89–97. Kim notes that a common form of the “appreciation formula” typically employed either εὐχαριστέω or χαρίζομαι and ran something like τοῦτο δὲ ποιῶν εὐχαριστήσεις μοι, where τοῦτο referred to the favor the sender had just requested.

[11] H. Koskenniemi, Studien zur Idee und Phraseologie des griechischen Briefes bis 400 n. Chr., Helsinki 1956, 67–68.

[12] Of the roughly 134 female names beginning with Τασουχ- and attested in the DDbDP, 115 (86%) of the attestations appear in documents from the Arsinoite. This percentage could actually be higher as 9 of the 134 documents that appear are listed as unprovenanced. There are only 10 documents in which names beginning with Τασουχ- have an attested provenance outside of the Arsinoite.

[13] On the etymology of names using Τασουχ see NB Dem. 1211.

[14] This is especially the case with the male counterpart to Τασουχ, which is Πετεσουχ, as names carrying this masculine root overwhelmingly come from the Arsinoite. See R. Alston, Trade and the City in Roman Egypt, in: H. Parkins and C. J. Smith (eds.), Trade, Traders and the Ancient City, London and New York 1998, 182. On the rarity of Πετεσουχ names outside of the Arsinoite see C. Préaux, La stabilité de l’Égypte aux deux premiers siècles de notre ère, CE 31 (1956) 327–338, who notes that it is only attested once in 5,000 Theban ostraca.

[15] N. Lewis, Exemption from Liturgy in Roman Egypt, PapCongr. XI (1966) 513–518, 523–526.